I’m a librarian, so by training and habit (and just because I’m made that way), I always read all pre- and post- material in a book — and I usually read it first. Jacket flaps, colophon, acknowledgements, introduction…. I even glance through the index and end notes, if there are any. And being a librarian, by golly, I strongly recommend that all readers do the same. You learn a lot about the nature and the flavor of a book that way.

I’m a librarian, so by training and habit (and just because I’m made that way), I always read all pre- and post- material in a book — and I usually read it first. Jacket flaps, colophon, acknowledgements, introduction…. I even glance through the index and end notes, if there are any. And being a librarian, by golly, I strongly recommend that all readers do the same. You learn a lot about the nature and the flavor of a book that way.

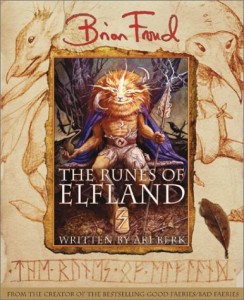

But not this time. This time I’m going to suggest that you not read the introduction to The Runes of Elfland first. Skip it. Please. Just flip over to page sixteen, where the book proper starts, and jump right in. Well, ok. I suppose you can read the foreword and the preface, if you want. But leave the introduction for a bit. Now, I’m not saying skip it altogether! You can come back to it later, and you’ll get a lot out of it if you do.

Why? It’s because The Runes of Elfland is the sort of book that might be called interstitial. Is it picture book? Is it book of fairy tales? Is a it rune dictionary? Yes. It’s all of those. In the introduction, writer Ari Berk tries to explain how it all fits together, but he ends up confusing the issue even more. It’s not his fault. He’s dealing with runes, after all, those ancient letters/symbols/spells that have more than one meaning and more than one purpose. And he’s dealing with faeries, folk who not only actively resist explanation, they actually take positive delight in turning it upside-down.

Brian Froud knows. As he says in the Foreword, “I looked at their [the runes] shapes, and images came to mind; then I painted for months.” And Dr. Berk knows, too, really. Perhaps he’s written the Introduction because he feels readers deserve some kind of warning, some preparation for what they’re about to experience. Or perhaps, as a professor (at Central Michigan University), he wants to give us a syllabus. Certainly his final words of advice before the action starts are wise:

“All storytelling is a form of travel. All the things you know you should do when travelling in this world apply to Elfland as well… Be polite. Don’t take anything without asking. Laugh at their jokes… Beware of dark woods at night. Do not trust the wolf in winter. Take notes. Sing for your supper. Pack extra sandwiches… Start early…”

So, that said, start. After all, dangerous as Elfland (also called Faerie) is, there’s a special grace for those who go in like children, open to wonder everywhere.

And what will you find when you start? Pictures. Froud’s months of paintings, pattering down the pages like leaves, like the leaves you idly watch falling in autumn before you suddenly realize that some of them are small brown birds, and are actually touching down and then taking off again! Brian Froud’s faery creatures here are weird, in the old sense of the word — and in the new sense, too. They’re beautiful or grotesque, funny or solemn. Some of them are forming the shapes of runes with their odd, twiggy bodies. Some are in drawings, in sepia on parchment. Some are in paintings full of layers of brilliant color.

The faerie throng presses closely around the runes, sometimes jostling them, but there’s order here, too, of a kind. The runic “alphabet” is laid out, one rune at a time. Accompanying each rune, along with the wealth of images, is a story by Berk, evoking the nature of that particular rune and sending the reader off on an imaginary path. For example, with the Rune of Companionship comes the story of the Fetch, a creature in Faerie who is, in some ways, your Other-self. When you meet the Fetch, what should you do? And can you answer the riddle of the Fetch?

“Not your face, nor your hair.

Not a piece of the pieces of your trunk.

I am upon you, though you are no heavier.

What am I?”

Berk also tells us bits and pieces of the lore surrounding each rune, some of which is faerie lore, and some human lore, passed down through our history. The Rune of Beginnings, for example, is also the rune of the Birch. The birch is a sacred tree representing beginnings, because it was the pioneer tree, the first tree to root in places where the ice sheets receded from the land, long ago.

In the margins, and sometimes hidden in the pictures themselves, are more runes, lines of runic sayings which are clever, dappled, funny or confusing. In the back of the book is a page with all the runes laid out in rows, their rough equivalents in the English alphabet underneath them. This may help you decipher the runic messages Froud and Berk have wound into the pictures and stories, or it may not. As the authors warn, “Elvish runic inscriptions are notoriously problematic. Some contain errors, puns or omissions that may annoy mortal sensibilities. Keep your wits about you.”

The thing of it is, runes do operate on more than one level. You can use them to spell your name, but then the runes you use may tell you something about yourself. The runes I’d use to write “Grey,” for example, could carry the message: “The one named has exchanged journeying for the motion of memory.” Or “She knows that the exchange between journey and memory — like the exchange between matter and energy — is in constant motion.” Or perhaps, “She has exchanged journeying for a hope of eloquence.” And that’s just a beginning.

Froud and Berk understand this multi-leveled aspect of meaning, and they use it here. Or perhaps they don’t use it so much as revel in it and strive to unfold even a little bit of it for us, their readers. So read the stories and the lore, look closely at the pictures and marginalia, and let your imagination take you even further than the pages go. Say the charms out loud. Write your name in runes. The authors want you to. They urge you to.

And then go back and read the introduction. It will make more sense to you now, but you’ll see how it doesn’t quite capture the book you’ve just explored. Nothing really can.

(Harry N. Abrams, 2003)