Ever wonder what happened to the Child ballads that came across the water? Have you been curious about the lives of the folks whose wavery voices emerge from Lomax’s home recordings? This book contains the answers, plus over one hundred New World cousins to those ballads collected by Child, transcribed by balladeer John Jacob Niles in his trips through the southern Appalachians during the 1920s and 1930s.

Ever wonder what happened to the Child ballads that came across the water? Have you been curious about the lives of the folks whose wavery voices emerge from Lomax’s home recordings? This book contains the answers, plus over one hundred New World cousins to those ballads collected by Child, transcribed by balladeer John Jacob Niles in his trips through the southern Appalachians during the 1920s and 1930s.

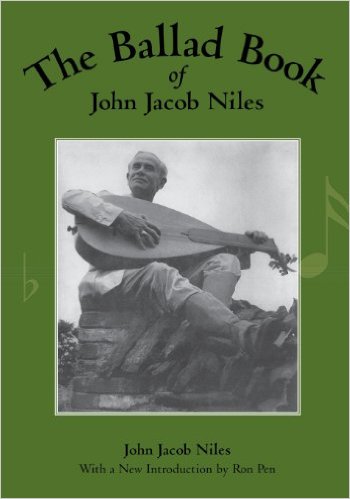

Niles’s career as a singer and folklore collector spanned several decades. In addition, he wrote some songs, including hits such as “Black is the Color” and “I Wonder as I Wander.” Niles began collecting ballads at the age of fifteen, and continued throughout his career, singing both traditional songs and

original compositions. His originals were such seamless representations and adaptations of the Appalachian tradition that he had to sue for copyright infringement to maintain credit for several of his songs. The notebooks that he used to validate his claim are the same ones that form the basis for the ballads in this book. In his introduction, Ron Pen, Director of the John Jacob Niles Center for American Music at the University of Kentucky, notes that these ballads were published after the highly politicized folk music revival of the 1960s, and thus failed to have an impact on the political situation of the times. The songs can be appreciated for their beauty, and many of them can still be heard on albums currently being released, but they were largely absent from the movement that brought American folk music out of the hills and onto the record players in the mid-twentieth century. Earlier Niles collections of sea songs and African-American worksongs had been released between the 1930s and 1950s, but represent much shorter and more limited dissemination of songs he collected.

The ballads are presented based on their ordering in Child’s collection, and given “Niles” numbers, along with the date and circumstances that led Niles to the songs. These stories of the characters that produced new songs for Niles on his journeys are wonderful little gems, glimpses of the world that produced “Barb’ry Ellen,” “The Farmer and the Devil (The Farmer’s Curst Wife”), “The Two Old Crows” (Twa Corbies”), and “Mary Hamilton.” Niles also gives a short history of the Child ballad, where the song or similar variants have been recorded, and some discussion of how the song evolved into its Appalachian form.

He reports that military songs and tales of the supernatural seemed to have faded out of consciousness, leaving a body of ballads of love and loss, of Robin Hood, the adventures of European nobility, and that perennial American favorite, murder. It is hard to tell whether this apolitical focus is due to his focus on the Child ballads in this book, but it is clearly at odds with the political focus of some of his contemporaries, such as Woody Guthrie, the Weavers, or Pete Seeger. It seems as if Niles wants to make a statement about the beauty of the music and the singers that precludes their lot being hijacked by city folks with ulterior motives.

If this was his aim, he largely succeeds. The songs and the musical transcriptions are well done, with variants of melodies and lyrics faithfully reported. The writing does have several irritating aspects as Niles attempts to reproduce the speech patterns of the region, consistently substituting “hits” for “its” and so forth. The prose is simple and direct, so much so that the flat American speech patterns almost jump off the page. But the stories are wonderful glimpses into the lives of people who sang the songs that they had learned in the home, the secular corpus that accompanied The Sacred Harp shape note singing so popular in the region. Niles takes several shots at politically-oriented folk music revivalists when he tells the story of a disgruntled singer whose set was cut short at a festival, but later was persuaded to sing for Niles when he caught up with him walking home in a huff and offered him a ride:

“There was a direct wire to the outside world, so that the festival promoters could keep the press and radio informed, hour by hour. There were also political overtones. However, a few local characters arrived, and there was some interesting folk music sung, The Master of Ceremonies asked him how many verses were in “The Sisters.” Pete said there were more verses than enough. The master of ceremonies (sic), thinking in terms of show business values, quietly led Pete Johnson offstage, and thereupon missed something of real importance.”

The people of the southern Appalachians had a great tradition of ballad singing, one that Niles obviously loved enough to share through his singing and by making his song collecting efforts available in this book and by leaving his notes to the University of Kentucky. This book provides a marvelous glimpse of 70 years ago when singing was a family entertainment, an almost daily pastime.

Readers who enjoy the North American traditional music as sung by today’s folk musicians and wonder where they get the songs will enjoy this book. Folks who are gone on the music enough to listen to the home recordings being released by labels such as Rounder will find this book to be a great resource. Niles’s stories and the songs themselves flesh out the line drawings of preservationist recordings. This book may even encourage readers to begin singing again themselves.

(University of Kentucky Press, 1960, 2000)