I was not prepared for this book.

I was not prepared for this book.

I knew from the title that the story was at least related to the classic silent horror movie, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, with which I am only passingly familiar. That was not as great a handicap as I’d feared, as the relevant aspects of the movie’s events are mentioned briefly in the book. In retrospect, I would still have watched the movie first, if for no other reason than to get a clearer sense of the characters and mood at the outset.

I did not, however, anticipate the amount of artistic theory and discussion that I would find within. The protagonist is a budding American artist who, inspired by an exhibition, travels to Europe at the dawn of WWI in an effort to study with the greats. They are having none of it, though, and so it is that he falls under Caligari’s spell. The doctor is operating an asylum in Germany, and the man who was to teach art classes to the inmates is instead destined for the war. Armed with the conscript’s letter of introduction, our hero takes the position in his stead.

The inmates we meet are delusional in a matter-of-fact sense, generally sane and rational save for a single aspect of their identities. So it is that they proceed to engage in numerous discussions of art theory with their new teacher, and the titular doctor’s behavior comes across as markedly more unhinged than his patients. Ultimately, though, the narrator and his alluring star pupil discover that Caligari has a malevolent artistic calling of his own, and their efforts to stop him lead them down an increasingly surrealistic path that leaves one utterly convinced of the transformative potential of compelling art.

Perhaps the biggest stumbling block for me was the deliberately old-fashioned prose. I have little doubt that it is stylistically in keeping with writings from that era, as the preference for obscure adjectives is positively Lovecraftian, but knowing that did not make reading it any easier. I had to digest this story in small bites rather than my usual large gulps, taking over a week to read the slim volume. I kept wanting to long-press certain terms – both German words and those unfamiliar adjectives – to look them up, but unfortunately my paperback copy lacks that particular feature. For that reason, I recommend reading this as an ebook if you have the option.

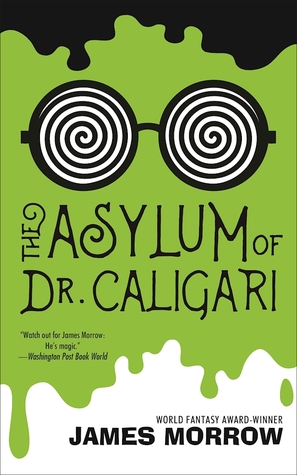

Overall, as much as I usually like Morrow’s work, I can only give this three stars out of five. For me, it was a four-star story hindered by the difficult background and prose style. Art aficionados are likely to appreciate it more than I did.

(Tachyon, 2017)D