Cat Midhir has stopped dreaming. People assure her that it isn’t possible, that she just doesn’t remember her dreams, but Cat knows they’re wrong. Where her dreams have been, there is only heaviness and loss. For Cat, this loss means more than it would to most of us, because she is that rarest of all dreamers, a person who returns to the same dream every time she sleeps. In her dream world live her truest friends and her only source of inspiration for the books and stories that have won her acclaim in her waking life…

Cat Midhir has stopped dreaming. People assure her that it isn’t possible, that she just doesn’t remember her dreams, but Cat knows they’re wrong. Where her dreams have been, there is only heaviness and loss. For Cat, this loss means more than it would to most of us, because she is that rarest of all dreamers, a person who returns to the same dream every time she sleeps. In her dream world live her truest friends and her only source of inspiration for the books and stories that have won her acclaim in her waking life…

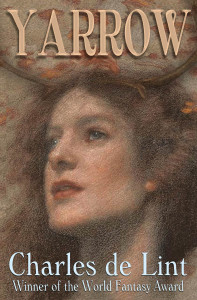

So begins Yarrow, one of the earliest books by Canadian author Charles de Lint. The protagonist, Cat — or Caitlin — Midhir, is a writer of fantasy novels. Her loss of her dreams forces her to turn to the outside world for the first time in an effort find friends who will help her bear the absence of her beloved Otherworld and its denizens. And friends she does find, in Peter Baird, a bookstore owner, and in Ben, a burly taxi driver and shy fan who nurses a secret crush on her. But she also, unbeknownst to her, has an enemy: Lysistratus, a creature who long ago ceased to be a man and continues his evil existence only by stealing and consuming dreams. Cat’s dreams are the strongest and most delicious Lysistratus has ever encountered. Far from ceasing to dream, she is instead feeding her dreams a monster — and he will refrain from killing her only as long as she continues to dream for him.

In her struggle against Lysistratus, Cat fights as well with her own fears of failure in the waking world, magnified by the gentle disbelief of her new friends, who see Cat’s dream life as imaginary. Cat knows that the Otherworld, its mysterious horned guardian Mynfel, Tiddy Mun the gnome and her oldest friend, Kothlen the bard, are all real. Tiddy Mun and his friends have even “crossed over” into the waking world from time to time, to hide in her house and play tricks on her. However, Peter’s reassurances that she has used her vivid imagination to create a better life for herself than the one she lives by day make too much sense. When she at last does escape Lysistratus briefly and enters her dream Otherworld for the first time in weeks, she finds it shattered, her friends fled or dying. And she wonders if perhaps Peter is right, and her subconscious is telling her through her dreams that it is time to “grow up” and leave her “imaginary” world behind. In the end, it takes an enigmatic encounter with Mynfel to show Cat the deepest truth about herself and her place as a person with a heart in two worlds.

Yarrow is set in de Lint’s Ottawa, the one he first envisioned for his novel Moonheart, and expanded in its sequel, Spiritwalk. Those readers who have fallen in love with the wonderful Tamson House of these two novels will be delighted to note its brief appearance in Yarrow as well. However, the characters in Yarrow are part of different story than the residents of Tamson House and their associates, and Yarrow is a stand-alone novel.

As with much of de Lint’s early work, Yarrow‘s fantastic elements are rooted in the Old World, particularly the folklore of the British Isles. The reader can see de Lint’s emerging ability, rough though it still is around the edges, to draw together the vivid, stylized characters who step out of folk lore’s vast tapestry and the harder, visceral immediacy of characters living in the modern world. Yarrow may be a fantasy, but it is also a fast-paced mystery thriller and a thoughtful character study. De Lint holds all of these elements together skillfully, but he does sacrifice some depth to do so. Yarrow lacks the multi-layered character development, for example, of some of his later books, such as Some Place to Be Flying. Yet, by the end of the novel, Cat’s Otherworld feels like a real place, a place with enough inner reality, enough substance, that it will continue to exist, in or out of dreams.

To the standard “author’s disclaimer,” in which an author assures the reader that “this is a work of fiction, none of the characters are real, etc.,” de Lint adds another sentence. “By the same token,” he says, “Cat Midhir’s writing habits, inspirations, and the course of her career do not parallel either my own or that of any other writer I know.” Well. Quite definite, isn’t he? And I can understand his desire to quash any over-ardent reader’s (or critic’s) attempt to use Yarrow to psychologize or “explain” him as an writer. Hence, tempting as that would indeed be, I will refrain. However, I will say that I personally do find Cat Midhir’s “night visiting” to be an excellent metaphor for the story-making process. When I engage in the world-making that is part of writing a story, I initially go into it like an explorer, finding my way. In the thickest part of the writing I become an inhabitant, living more fully in that fictive world than in reality. But when I’ve done, I look back and see that I have become the Fate of my own world. I know all of its secrets, and my own words have spelled its magic. It will open its doors for me, and it trusts me to protect and renew it. I have become a sort of Mynfel for that world.

You can find the Triskell Press digital edition here.

(Pan Books, 1993; Triskell Press, 2015)