Stephen Hunt penned this review.

After doing extensive research, I can definitely tell you that single malt whiskies are good to drink. — Iain M. Banks

After doing extensive research, I can definitely tell you that single malt whiskies are good to drink. — Iain M. Banks

On Friday, 21st March 2003, I celebrated my forty-first birthday with a sense of genuine contentment. Twelve months previously I’d been the willing recipient of a huge outpouring of affection from my friends, and the somewhat less willing recipient of a thousand “over-the-hill” remarks from people that I now choose to describe merely as acquaintances.

I’ve discovered that while turning forty is generally considered to be a “landmark” occasion (worthy of the mother of all parties), forty-one is the age that marks the real turning-point. I am now, officially, “a Middle-Aged Bloke,” which is, in fact, an immensely liberating thing to be in the youth-obsessed culture of early 21st Century Britain. No one expects a “MAB” to wear expensive, fashionable, uncomfortable clothing, recognise soap-opera starlets or hold a valid opinion on “drum ‘n’ bass” music. Best of all, being a MAB allows one to pursue a public enthusiasm for single-malt whisky with absolute impunity. For a younger man, the people who work behind bars are real authority figures, liable to demand proof of age, serve a short measure or simply scowl, threateningly. The MAB, however, has elevated to a higher plane, beyond the reach of such petty tyrannies. Ask for a single-malt from one of the older examples of the species and you’ll get an approving “excellent choice, sir,” in reply. The younger ones, meanwhile, will adopt a look of mildly incontinent panic until you patiently point to the bottle of strange, golden, oily liquid that you’re requesting, express gratitude that you’ve corrected their pronunciation of “Glenmorangie,” and splash in a little extra to make sure that you go away quickly and stop frightening them. It is, to use a very un-MAB phrase, “a win-win situation…”

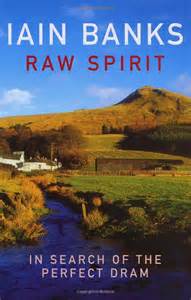

And so I address myself to the matter in hand, the very pleasant task of reviewing Raw Spirit — In Search of The Perfect Dram by Iain Banks, “Uber-MAB” and (according to The Times) “the most imaginative British novelist of his generation.” The central premise of the book is that the author undertakes a mammoth road-trip around Scotland, tours its numerous distilleries, and recounts his adventures and experiences along the way. Given that Banks’ four principal passions appear to be writing, the driving of exotic four and two-wheeled machinery, whisky and his native land, this, as he cheerfully admits, is a “cushy” gig.

Now, the idea of a “cushy” gig (even one cheerfully admitted to) is not something that British “MAB’s” readily warm to. We have a tendency to “hate it when our friends become successful” (as The Smiths so beautifully coined it). Even the great Billy Connolly (long-term holder of “The World’s Greatest Living Scotsman” title), blows it spectacularly from time to time. When he appeared on our TV screens recently, sanctimoniously eulogising Ireland and Scotland, and talking about his “wee tingling sensation” and “sense of being where I belong,” the entire British Isles briefly resonated to a tremendous flatulent raspberry and cries of: “so, why the fuck do you live in L.A. then, Billy?” But I digress….

Banks manages to head my unpleasant cynicism off at the pass, before he’s even left the introduction. “This, let’s face it,” he declares, “is a book about one of the hardest of hard liquors and for all this let’s be mature, I just drink it for the taste not the effect, honest, Two units a day only stuff… it is, basically, a legal, exclusive, relatively expensive but very pleasant way of getting out of your head.” The author, I immediately deduce, is a man blessed with an abundance of that most uncommon of attributes — common sense. This is a man that I’m happy to undertake the journey with. That journey begins (in chapter one, obviously), with the date Friday, 21st March 2003, the day of my ascension to middle-aged blokedom. This, I decide, is truly auspicious….

“Aye, a bottle o’ the best, that’s what it is, nae idle jest Nae Mickey Finn, nae rotgut gin, nae bathtub wine that tastes like Vim Have no fear, it’s not like beer; malt whisky’s strong and bright and clear And it’s also bloody dear, but what the hell.”

To fully appreciate the journey that Banks writes, it’s definitely helpful if the reader is a fellow imbiber of “the water of life.” Early in the book, Banks reveals “Willy’s Definitive Dram Definition” (Willy being a distillery worker who he encounters), as: “a measure of whisky that is pleasing to guest and host.” Therein lies the crux of the matter. For while, as already declared, the stuff is basically a powerfully effective intoxicant, its specific effects are undoubtedly best enjoyed in company, rather than as a solitary pursuit. (Solitary whisky drinking, it should be noted, is usually called “alcoholism,” which is neither the subject of this book, nor advocated by this reviewer).

If former Fairport Convention singer Trevor Lucas provided the most memorable paean to cannabis (“marijuana, Australiana, cheaper than booze, safer than pills, makes you sing like Frank Sinatra”), then the definitive word on whisky is surely that penned by novelist Ivor Brown (“plays the New English Dictionary like an accordion” — The New York Times): “Whisky, properly savoured and not grossly gulped, is essentially a pensive and philosophic liquor.”

Banks, whether knowingly or unwittingly, has digested Brown’s truth and created a narrative which is not merely about whisky (its history, manufacture, and properties) but encapsulates and articulates the joyous conversational experience of actually slinging it down your throat. This is an aspect of the book that seems to have been either overlooked or derided by some of Banks’ critics. A Green Man colleague found the frequent references to the events of the Iraq war (concurrent with Bank’s road-trip), to be “distracting.” I, on the other hand, found myself smiling in rueful empathy at the way the author addressed the horrific topicality of the war, the wonders of a decent curry, the trials of following a lower-division football team, the comfort of long-term friendships and the significant events of history as equally important matters of immediate discourse. David Horspool, meanwhile, in his witheringly dismissive Guardian review said: “As a novelist, Banks’s qualities are imagination, a dark inventiveness and teasingly structured narratives. As a travel writer, he just jumps in the car and busks it.”

Now, far be it for me, a writer whose principal motivation is the shameless gleeful garnering of limitless desirable freebie CD’s and books from the GMR editors, to presume to actually disagree with a learned wordsmith like Horspool, but “busking it” is, in my hard-gained and literal experience, a branch of the performing arts not to be dismissed lightly.

Buskers are singers, musicians and poets, whose task is to connect with an audience at street-level. Certainly there’s a stated awareness of folk music in this book — the author acknowledges his friendship with a member of Shooglenifty and makes a passing reference to Mike Scott. Arguably, there’s even a Bardic quality to the best writing here. Perhaps that’s just the drink talking (hey, even reviewers have to “research,”) but let’s examine the evidence….

When Banks writes about Glenfinnan, officially the rainiest place in Britain, he comes up with the following sentence: “People notorious for having had the bad luck to have been born and raised in Fort William during a particularly catastrophic sequence of above-averagely rainy decades of seriously god-awful drenchingness — and hence no strangers to having apparently unending successions of black, moisture-laden cumulonimbi queuing up above their town to deposit megatons of water apparently targeted specifically on that individual’s cagoule hood — have been known to blanch and stagger when confronted with the prospect of spending longer in Glenfinnan than the amount of time it takes to drive — splashing — through it.”

That, by anyone’s reckoning, is a torrent of words, is it not? Likewise, when Banks writes of the “Great Wee Roads,” that constitute his favoured routes of traversing The Highlands and Islands, his narrative twists and turns, brakes and accelerates, favours the “pensive and philosophic” over the fast and direct. This is an old and cunning story-telling technique, this symbiosis of form and function. You’ll find it in the balladry of Dick Gaughan and Robin Williamson (two more strong contenders for that “Greatest Living Scotsman” crown), just as in Raw Spirit. That title, one suspects, is, itself, suffused with layers of complexity that run deeper than the obvious or superficial.

Did I just say “complexity?” That, in a word, is what single-malt whisky is all about. Complex flavours, complex history, complex politics, even, for the drinker, a complex relationship with the beautiful, beguiling, complex poison itself. The catch, of course, is that for all its complexity, it’s also very easy. The liquid’s very easy to drink and the book’s very easy to read. This, perhaps, is what has drawn the ire of Banks’ fiercest critics. This is not, by any means, the first book on the subject of single-malt whisky that I’ve read, but it’s easily the most accessible. Most whisky writers seem keen to establish themselves as connoisseurs, men (and yes, they’re inevitably men), of taste and discretion, rather than mere “blokes” who can pick up a bottle of Islay’s finest on a trip to the local supermarket, for the price of a half-decent blend. All that stuff in Banks’ introduction about “basically, a legal, exclusive, relatively expensive but very pleasant way of getting out of your head,” is anathema to those writers.

This is an important book that both reflects and contributes to the de-mystification of its subject matter. If either the author, the reviewer or the drinker occasionally lapse into silliness or irrelevancy, well that friends, is entirely in the nature of the whole shebang.

Here’s a final tale from my own experience (what do you mean, self-indulgent? I’m being “pensive and philosophic, ok?”) to illustrate that last paragraph.

In the August of the year of my “Middle-Aged Blokehood,” I had the good fortune to take the distillery tour at Middleton, Co Cork, ancient home of Jameson’s Irish Whiskey. At the tour’s conclusion, the very efficient, smart and attractive lady tour guide asked for four volunteers to take part in a “just for fun” tasting of various examples. Mine was the second hand to be raised (narrowly beaten to the punch by my dear wife), along with two other men. We all dutifully and happily slurped down small glasses of the various (excellent) products of Erin’s Isle, grimaced in repulsion at the indescribable awfulness of the Kentucky Bourbon (sorry, Mr Beam), and declared ourselves unimpressed with the token, comparative Scotch. “Ah,” said our guide, raising her voice with an air of practised triumph, “so you all agree that the Irish whiskey is superior to the Scotch?” What followed was, to the poor woman, at least, an entirely bewildering and unscripted four-way discourse about what is actually meant by the word “Scotch.” The two fellow “tasters,” one a former helicopter pilot, the other a retired officer from the British Army, suddenly found a new, unexpected friend in a scruffy, unkempt, long-haired folk musician (me) as we chatted knowledgably for a good hour about the various joys of Highland Park, Laphroaig and Glenlivet. I’d love to surprise those guys by buying them both a copy of Raw Spirit — they’d appreciate it as much as I did.

“I’ll not touch Teachers, Grants nor Haig, gie me Bowmore or Laphroaig, Glenfarclas in a glass, well ye can throw the top away For there’s no use tae pretend that ye’ll need the top again When ye’ve broken oot a bottle o’ the best.

###

This review was written over Hogmanay, 2003, under the influence of Ardbeg and Glenmorangie Port-Wood Finish, both of which, I’m delighted to report, meet with the approval of Mr Banks.

The song lyrics quoted are from Jack Foley’s “Bottle O’ the Best,” and are best heard sung by fellow staffer Alistair Brown, my final contender for that “World’s Greatest Living Scotsman” thingy….