Yes, I had a press ticket. Yes, I went to the earliest possible showing yesterday, opening day (December 18), and refused to eat any popcorn or drink any soda, lest I be distracted even minutely from the film. Yes, I am an obsessed fan of J.R.R. Tolkien. Actually, I prefer “devoted.” (There are different sorts of obsessed, err, devoted fans. Cat Eldridge, our Editor in Chief, collects all sorts of special editions of Tolkien’s work, and has reviewed the extended-release DVD of The Fellowship of the Ring for this issue. I, on the other hand, have among my most prized possessions the tattered paperback of The Smith of Wootton Major and Farmer Giles of Ham that I first read as a child, and a copy of “The Red Book” in which some of my dearest friends have written their favorite passages or quotations on the fly leaves and end papers. I think of Tolkien as one of my grandfathers.) The point being that if you want an unbiased opinion from a viewer who came to the movie yesterday without any preconceived notions as to what it ought to be… well, I’m sure they’re out there.

Yes, I had a press ticket. Yes, I went to the earliest possible showing yesterday, opening day (December 18), and refused to eat any popcorn or drink any soda, lest I be distracted even minutely from the film. Yes, I am an obsessed fan of J.R.R. Tolkien. Actually, I prefer “devoted.” (There are different sorts of obsessed, err, devoted fans. Cat Eldridge, our Editor in Chief, collects all sorts of special editions of Tolkien’s work, and has reviewed the extended-release DVD of The Fellowship of the Ring for this issue. I, on the other hand, have among my most prized possessions the tattered paperback of The Smith of Wootton Major and Farmer Giles of Ham that I first read as a child, and a copy of “The Red Book” in which some of my dearest friends have written their favorite passages or quotations on the fly leaves and end papers. I think of Tolkien as one of my grandfathers.) The point being that if you want an unbiased opinion from a viewer who came to the movie yesterday without any preconceived notions as to what it ought to be… well, I’m sure they’re out there.

I said in my review of The Fellowship of the Ring last year that I could not say enough good things about the sets. I’ll say it again. The settings in The Two Towers are simply stunning. Over and over I was able to see my most cherished imaginings take shape before my eyes, and they were right! Edoras, with its buildings reminiscent of Viking architecture, is a fitting capital city for the “horse people” of Rohan. I live in Colorado, in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains, and I’ve been inside NORAD, and I can tell you with conviction that Helm’s Deep fits perfectly into that chink in my mind labelled “mountain fortress.” I deeply respect and admire Alan Lee, whose vision and tireless work as conceptual artist and set designer made these things possible.

But if the larger settings create an appropriate tone for the story, the small details provide a dense, layered sense of reality that I’ve never seen in another film endeavor (sorry, Mr. Lucas). King Theoden’s sword has as its pommel the arching heads of two horses, facing one another, forged in simple, early Viking lines. All of the races are carefully conceptualized, and their accoutrements reflect their various natures; the ornamentation on Gimli’s Dwarvish gear is angular and geometric, whereas every weapon, lamp, or belt the Elves carry is designed with graceful, entwining curves. When Treebeard walks, his feet literally “plant” themselves on the ground, his toes digging into the loam like roots.

Which brings me to my next enthusiastic gush: the special effects are outstanding. Although the Ents are not quite how I’ve always pictured them, I had no trouble at all accepting them as Ents. Neither did I have any doubts that Gandalf is riding Shadowfax without reins — although as a reviewer I dutifully examined the technique. The Gollumness of Gollum is wonderful. Not being as techie as some, I glossed over the reports of how the actor was dressed in blue, and then the lines of Gollum’s figure were painted on him, and then CGI enhancement…. suffice it to say, it’s convincing. As is the battle at Helm’s Deep. The sight of thousands of orcs swarming up to the stone wall, with the pale faces of the defenders like beads lining its rim… And the Orcs themselves are beautifully, hideously Orcish, to the last detail. And the Wargs are nastily toothy, and the Nazgul are sinuously, wormily draconic. Not to mention the Oliphants. John Howe, we’re not worthy.

The music, once again, adds a crucial dimension to the setting, almost unnoticeably evoking the mood for each scene. The theme for Rohan is a yearning violin melody, perfect for Rohan’s gallantry and forlorn, wavering hope. The first time it played, I turned to the person sitting next to me and said, “Looks like I’ll need to buy another soundtrack.”

“Alright, already!” I can hear you saying. “Music, schmusic! What about the people? What about the story?”

I’m pleased with the casting choices and acting of each of the characters introduced in this film. I’ve imagined Eowyn as taller, colder and paler, but Miranda Otto plays her with a fresh-faced vigor that suits a young woman who grew up on horse back. Karl Urban as Eomer is heart-poundingly good; he’s the perfect proud young warleader, the horse plume on his helmet tossing in the wind. And Theoden (Bernard Hill) looks as though three score years of cold wind have battered him and left him unbowed.

I’ve been waiting with bated breath for Faramir. David Wenham does not disappoint. Faramir is a key character, because he needs to both lead and follow; his nobility is that of a man who loves his father and his king unreservedly, and seeks to do what is best to serve them. He could easily appear weak, because he never seeks power or glory for himself. But Wenham acts with his face and his voice to strike the right balance. As Faramir, he is clearly the decisive, respected leader of his men, while remaining quietly observant and thoughtful. I can believe that his level, clear gaze sees many things that people might wish to hide.

And did I mention how wonderfully Gollum is Gollum? Jackson et al. decided to enhance the duality in Gollum’s personality, showing the conflict between suspicious, Ring-driven Gollum and the yearning, lonely Smeagol, longing to come out of the dark. This was a controversial decision, but I think it works. Gollum/Smeagol is repulsive, never doubt it. But his Smeagol side caught my sympathy in a way that surprised me. I can see now why neither Bilbo nor Gandalf could simply ring his neck when they had the chance, regardless of how much he deserved it.

The returning characters are a mixed bag. Orlando Bloom as Legolas continues his virtuoso “kick-butt Elf” performance — he drew more spontaneous cheers from the audience than anyone else. He acts with his eyebrows, conveys sarcasm with the smallest twitch of a lip, and boogie-boards down a flight of stairs on an Orc shield with reckless flair. Gimli (John Rhys-Davies) is disappointing in the main. When they let him be a soldier, he’s thunderously awe-inspiring; he swings his axe like it’s a feather, and shakes Orcs off his back like snow. But the writers decided to play him as the fall guy for humor and pratfalls. This silly, buffoonish Dwarf, calling Aragorn “laddie” and humphing peevishly because he’s too short to see over the battlements of Helm’s Deep, is not the fierce-tempered, gruff character that Tolkien wrote. I can’t respect this Gimli, and that’s a pity.

Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen) is improved this time out, in my opinion. He’s much better tracking Uruk Hai and walloping the heads off of Orcs in death-or-glory charges than he is sitting around and brooding about failing like his ancestor, Isuldur. Except for his forgettable scenes with Arwendy (and I know at least three people who will be disgusted with my opinion on this, but there it is), he makes a strong showing. Ian McKellan continues to excel as Gandalf, his new incarnation as Gandalf the White flawlessly powerful. The scenes where he blazes forth in light and glory could be hoky, were an actor with less force of personality playing the part.

Frodo (Elijah Wood) continues to deteriorate, in a way that makes my heart bleed. The Ring is taking over his mind and heart. And his physical weakness grows. There’s a small scene, late at night, in which he lies sleepless, stroking the Ring lovingly with one finger. It made me shudder. Sam’s (Sean Astin) bluff cheer is the perfect foil. A friend and fellow reviewer objected to his harsh treatment of Gollum, but it’s there in Tolkien’s story. It does look a bit more nasty onscreen than I expected, it’s true.

Merry (Dominic Monaghan) and Pippin (Billy Boyd) are played more two-dimensionally this time around. It’s been about twenty-four hours since I left the theatre, and already I can remember little that they said or did in any detail, except for Merry’s quick-thought dropping of his Lorien brooch to make a trail for Aragorn during their captivity with the Uruk Hai. Hopefully, their chance to shine will come in Part Three.

OK. Maybe I shouldn’t have left the plot until last, but I have some serious criticisms and I’ve been dreading making them. Let me start by saying that much of the plot is splendid, and the translation of Tolkien’s words to the silver screen is more than I could have hoped for. The riding of the Rohirrim, and the way their horses sweep in a wide, galloping circle to surround Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli, took my breath away. It’s one thing to read about it. It’s another to see it. The charge of Theoden out of Helm’s deep, the blowing of the great horn of Helm, in fact the entire battle sequence there, are riveting and deeply satisfying.

But Jackson and his fellow writers have made some plot changes that are on the surface senseless, and on a deeper level quite troubling. For the first, the Ents decide in their Moot not to join in the war and go to Isengard. Pippin and Merry have to trick them into fighting by making Treebeard “accidentally” come upon a burnt-out section of Fangorn Forest. This is so wrong that I had to keep myself from shouting with outrage and despair. Treebeard and the Ents are tree-shepherds. As Tolkien writes them, they know from the first axe stroke that the orcs are trying to destroy Fangorn. Making them isolationist cowards, rather than centuries-old, deep thinking people who must weigh everything into the balance before they take action, robs the story of one of its strongest elements.

And then there’s the debacle of Faramir. Great Elephants! Faramir wants the Ring? Faramir takes Frodo and Sam prisoner and drags them to Osgiliath? No! As I wrote above, the key to Faramir’s entire character is that he does not want power. He wants to do right. His heart is wholly given to his allegiance, but he refuses to take the ring, even for Denethor, even knowing that his refusal will enrage and disappoint his father. By robbing him of this, Jackson and associates have robbed us, too.

Why did they make these changes? Was it because, as Ken Myers of NPR has suggested, “Movies are different from books. They move”? Did they think the plot would flow faster this way? I can’t see how that could be the case. Tolkien, it is undeniably true, wrote many more paragraphs about the landscape than he did about the battles. It is necessary in a movie format to give more space to Helm’s Deep than to Frodo, Sam and Gollum wandering through the Dead Marshes and Ithilien. But they added long, slow scenes, not in the original story, of Aragorn and Arwen emphasizing their love yet one more time through sighs and liplocks and dream sequences in whispered Elvish. Why not lose that and keep the rousing march of the Ents? “To Isengard! Though Isengard be ringed and barred with doors of stone; though Isengard be strong and hard, as cold as stone and bare as bone, we go, we go, we go to war, to hew the stone and break the door!” What could be more moving than that?

Or did they make the changes, as another friend suggests, because they didn’t want anyone but the main characters to appear heroic? If that’s the case, they applied the rule unevenly, because they forgot to mess with Eomer — he shines as valiant as ever, thanks be! And if that’s the case, then they have made a significant, global change to the story. Tolkien meant to show that people everywhere, when roused, can make a stand against evil. If only the people in the spotlight get to say the brave words, where does that leave Middle Earth?

I left the theatre yesterday with a strange mixture of delight and sadness. I smiled at the whole row of young girls dressed to vaguely resemble Elves. I promised I’d call my friend later to “grouse.” I’m still looking forward to next year, in fact I’ve already begun the countdown to the release date of The Return of the King. But I can’t escape my conviction that Peter Jackson let us down, for reasons I don’t understand.

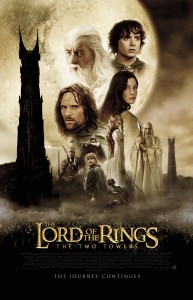

(New Line Cinema, 2002)