There was once a king. On the eve of his coronation, he spent the night alone in the forest, as was customary, to prove his bravery and his worthiness to rule. A vision came to him of a beautiful golden chalice, wrapped in fire. A voice said, “You have been chosen to be the keeper of the Holy Grail, God’s symbol of divine grace. With it you will offer healing for the hurts of men.” But the young king, eyes clouded by his own inner visions of power and glory, reached into the fire to take the Grail, and his hand was terribly burned. The Grail vanished. Over the years, the king’s wound grew worse. He devoted all his strength and the strength of his people to find the Grail, but to no avail. At last he took to his bed and began to die.

There was once a king. On the eve of his coronation, he spent the night alone in the forest, as was customary, to prove his bravery and his worthiness to rule. A vision came to him of a beautiful golden chalice, wrapped in fire. A voice said, “You have been chosen to be the keeper of the Holy Grail, God’s symbol of divine grace. With it you will offer healing for the hurts of men.” But the young king, eyes clouded by his own inner visions of power and glory, reached into the fire to take the Grail, and his hand was terribly burned. The Grail vanished. Over the years, the king’s wound grew worse. He devoted all his strength and the strength of his people to find the Grail, but to no avail. At last he took to his bed and began to die.

Then one day a wandering fool came to the castle. Coming in, he found the king, wasting away in his death bed. Taking pity, he asked, “Is there anything I can do for you?”

“I’m thirsty,” the king replied. The fool found a cup by the bed, filled it with water, and offered it to him. As the king drank, he found that his wounded hand was healed. And as he looked, he saw that the cup in his hand was the shining, divine Grail. In amazement, he turned to the fool and said, “How could you find what my bravest and best could not?”

“I don’t know,” the fool replied. “I only knew that you were thirsty.”

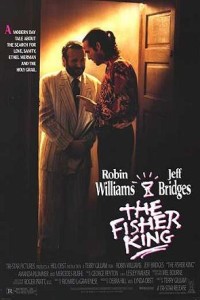

Jack Lucas (Jeff Bridges) is a popular trash radio personality in New York City. One day his flippant, cruel remarks persuade a troubled listener to open fire on the customers of a posh night club, killing several people, before turning the gun on himself. Jack, shattered by the distructive impact of his careless words, retreats into suicidal paranoia and takes to drinking heavily and wandering the streets at night. He is kept alive by the kindness of a generous video store owner, Anne (Mercedes Ruehl), who loves him despite his brokenness.

It is on the streets, three years later, that Jack meets Parry (Robin Williams), a homeless man who believes that he is a knight on a holy quest, chosen by God to retrieve the Grail. There are but two obstacles in Parry’s path. One is the Red Knight, a terrible foe whom only Parry can see. The other is the fact that the Grail, to ordinary eyes, is merely a trophy on the library shelf of one of the richest men in the city. The Little People have come to Parry, however, and informed him that Jack is The One, sent by God to help Parry overcome these obstacles and achieve his quest.

Through the strange synchronicity of grace, Jack discovers that Parry is actually a Medieval scholar whose wife was one of those killed by Jack’s troubled listener years ago. The tragedy destroyed Parry’s mind, and he now wanders the streets with no memory of his former self. Wracked by guilt, Jack decides to make reparation to Parry by means which he himself understands; he offers Parry money, tries to get him off the streets, and helps him meet Lydia (Amanda Plummer), a woman to whom Parry has pledged his love from afar, in traditional knightly fashion. None of these things are enough, however. In the end, Jack must accept the wisdom of Parry’s foolishness and assist him in fulfilling his quest.

The Fisher King is a modern fairy tale after the pattern of stories by authors of urban fantasy like Charles de Lint. Like de Lint, scriptwriter Richard LaGravenese gives us a story in which an indentured servant and a victim of the urban jungle are redeemed by a traditional quest, by their acceptance of roles which echo some of the deepest archetypes from our collective human myths. In this story, those archetypes are the wounded king and the holy fool. However, we also see that in this redemptive quest, the heroes must play both roles to find their Grail.

In the beginning of the movie, Jack is clearly the wounded king. One of his trademark lines during his shocking, sordid shows is a sarcastic, “Well, forgiiiiive me!” He has clearly rejected his opportunity as a radio personality to bring healing to his listeners, and so is burned by his prideful grasp for power and glory. Ironically, a television comedy is made with a character based on Jack’s life, and as he wanders drunkenly, fallen completely from that former life, he hears his own line over and over every night: “Forgive me. Forgive me.” Yet he is unable to find any forgiveness for his hubris.

In meeting Parry, Jack finds the fool who will quench his thirst. Parry’s love for life, his insistence on the ideals of Medieval knighthood, and his innocent trust in Jack as The One who can help him fulfill his quest, touch Jack’s heart and bring him out of his morass of guilt and self-pity. By involving himself in Parry’s insane yet delightful world, Jack reaches for life again.

Yet at the same time, Parry is also the king carrying a crippling wound. His memory of his wife’s horrific death weighs on his mind. He is pursued by The Red Knight, a monster wearing a penumbra of flame and tattered scarlet feathers, trailing a massive cloak of flapping, ragged red ribbons. No one but Parry and we, the viewers, ever see this demonic knight. To Parry, he is an unholy foe who cannot be overcome; to us, he clearly represents the blood and shattered bone that exploded from Parry’s wife to spatter and burn his world to pieces.

Only when Jack agrees to think like Parry, to accept his broken vision of the world, can Parry be healed. When Parry sinks into catatonia after a disastrous encounter with the Red Knight, Jack weeps by his hospital bed, trapped in his own guilt for bringing this on Parry. He shouts into Parry’s unresponsive face, “There’s nothing special about me! What am I supposed to do?” At last he decides to break into the millionaire’s library and retrieve the Grail. “If I do this,” he tells Parry, “it’s because I want to do this, for you.” And when he succeeds and brings the Grail back to place it in Parry’s hands, he is the fool who is willing to give the king what he has asked for, because the king has told him that this, and nothing else, is what he needs.

Terry Gilliam directs The Fisher King with an expert hand. He portrays Parry’s delusions by blending them seamlessly into the busy street life of New York. The Red Knight gallops thunderously through pedestrians on a 2,500-pound Percheron, “combining elements of Dante, Albrecht Durer, and Hieronymous Bosch,” as David Morgan wrote in the Los Angeles Times. When Parry watches his true love, Lydia, fight her way through a subway crowd, he does not see a swarm of homeward-bound commuters. Instead, Gilliam hired a thousand extras to dress as commuters and begin waltzing in the subway station, turning Lydia’s struggle into a graceful dance as she dodges Hassidic Jews waltzing with office workers and homeless people swirling with briefcase-bearing power brokers. The seamless flow between the reality the rest of the world sees and the off-kilter beauty of Parry’s reality — even the Red Knight is bizarrely, ponderously beautiful — allows us as viewers to suspend our disbelief and understand, if only for a moment, that a king might be healed by a drink from an old trophy cup, that the trophy cup can be the Grail itself, “God’s symbol of divine grace.”

(1991)