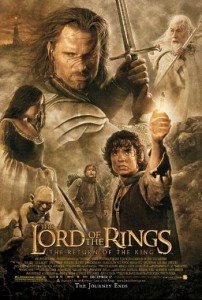

I’ve never laughed and cried so much in one movie. The thing is, I’m not a big movie crier. Those of you who read my Seabiscuit review are thinking, “Yeah, right!” It’s true, I swear. But I think I went into this one with the pump already primed. As I’ve said before, I love The Lord of the Rings, and I’ve spent my life since the first time I heard the story read aloud (by my dad, when I was seven) wishing for it to be made into a movie.

I’ve never laughed and cried so much in one movie. The thing is, I’m not a big movie crier. Those of you who read my Seabiscuit review are thinking, “Yeah, right!” It’s true, I swear. But I think I went into this one with the pump already primed. As I’ve said before, I love The Lord of the Rings, and I’ve spent my life since the first time I heard the story read aloud (by my dad, when I was seven) wishing for it to be made into a movie.

You’d think my devotion to the books would make me a hard fan to please. But really, all I was looking for were movies which showed that the people who made them were as devoted to the story as I am. Peter Jackson and Company have given me what I was hoping for, heaped it all together like a glittering dragon’s hoard, and poured it into my lap.

I admit, just like The Fellowship of the Ring and The Two Towers, The Return of the King a la Jackson et al. left out things and made changes that I’m not too happy about. To get my grumbles out of the way, I find the introduction of a rift between Frodo and Sam — fostered by Gollum — to be gratuitous meddling. It isn’t necessary, and it eats up precious screen minutes. Minutes that could have been better spent showing the romance between Eowyn and Faramir. Yes, my friends, they leave out the wonderful scene between Eowyn and Faramir on the parapet of Minas Tirith. Arrrgh! Arwen gets to fill the screen with more sighs and tears, but the romance Tolkien actually wrote is missing! Ahem. OK, I’m alright now.

And yes, you did hear correctly: there is no Scouring of the Shire. My disappointment about this major change to the story runs very deep. I’ve heard the reasons for it. I accept that Jackson and his fellow script writers chose to interpret the story this way. I just think the interpretation is wrong. The hobbits returning and discovering that evil has reached its long arm all the way back to the Shire and must be vanquished on their home turf is an essential element of what Tolkien was trying to communicate.

That said, there are so many wonderful things in this film that I actually broke my own rule and scribbled some of them down as I was watching, just so I wouldn’t forget. Stirring, poignant and beautiful moments come thick and fast.

I loved watching the beacons being lit on snowy mountain peaks all across Gondor, to summon aid in their time of need. I loved watching the White Wizard (Gandalf) ride out of Minas Tirith and smite the Nazgul with a beam of light to cover Faramir and his men as they gallop back hell for leather from Osgiliath. Later, when the city is under serious attack, breaking to bits from the assault of the orcs’ catapults, the defenders defiantly load their trebuchets with broken pieces of the city wall and sling them back out into the midst of their foes. A splendid touch — Tolkien didn’t write it, but I know he would have, if he’d thought of it.

Naturally, Eowyn’s killing of the Witch King brought cheers from the packed theatre, as did Aragorn leaping ashore at the eleventh hour, followed by the armies of the dead.

There are also moments that capture perfectly the sorrow and confusion of war. When Gandalf takes Pippin to Minas Tirith, partly to protect him from the power of the Palantir, Pippin weeps and reaches for Merry. “We’ll see one another again soon, won’t we?” Later, a maddened Denethor sends Faramir back to Osgiliath, a mission that means certain death. As Faramir sets out with his doomed men, Denethor sits alone in his echoing hall, eating a luxurious meal. He demands that Pippin sing for him. Pippin sings an a cappella lament (Billy Boyd, as Pippin, has a lovely voice for the simple melody), and the scene shifts back and forth from the grim desperation on Faramir’s face as he rides, to Denethor’s horrible solitary feast, to Gandalf sitting outside, alone, bowed over his staff.

Frodo and Sam’s final struggle toward Mount Doom is almost unbearable to watch. I cheered when Sam defeats Shelob, and when he fights through the tower to rescue Frodo from the orcs. But the pain, thirst and exhaustion the hobbits endure in the final days of their quest are almost too well portrayed. Frodo attacked and battered by enemies made me outraged. But Frodo with dried, cracked lips, staggering through heat and rubble, made me miserable.

Which leads me to one thing that stands out in this film overall. The acting is superb. Whatever changes may have been made in the story to various characters or roles, every actor plunges fully into the role they were given. No one holds back. I felt that if the role had called for them to burst their hearts, all of them would have, without hesitating. And the secondary characters don’t act “secondary.” Karl Urban as Eomer, Miranda Otto as Eowyn, David Wenham as Faramir: all of them play their characters as fully-realized people with complete lives and strong aspirations. When Urban and Viggo Mortensen (as Aragorn) are onscreen at the same time, they sit on their horses as brother kings, both strong, neither dominating.

As I said in my Two Towers review, I was fiercely hoping that Merry and Pippin would get their chance to shine this time. They do. Do they ever! They stay hobbits, easily stirred to sorrow, shame or glee. But they leap headlong into their brave deeds. It’s even better onscreen than in the book (don’t quote me on that, I’ll deny everything!). Merry gets to stab the Witch King in the ankle, so that Eowyn can finish him off. Pippin gets to use his impulsiveness to save Faramir. They get to ride into battle, and cheer Frodo from the Black Gate. I am so glad. I know I’m a little overinvolved in this story, but Pippin and Merry are like brothers to me. I’m proud of them.

Emotion flows freely throughout, without either embarrassment or schmaltz. I’ve rarely seen a movie that could do this so well. Strong men — not just hobbits — cry. And when the Fellowship reunites at the end of the quest, they embrace, they laugh for joy. When Frodo says good-bye to Sam at the Havens, he kisses him.

To make this work, Jackson keeps a steady hand on the overall mood of the film. He chooses to play it straight, with no over-the-top effects. Scenes with pathos stay serious — no extraneous humor injected to “lighten the moment.” Don’t get me wrong, there’s plenty of humor; but it’s humor that arises naturally from the circumstances of the story.

One of the people I was with remarked that the way the film is shot contributes to the effectiveness of its “feel.” Jackson uses no trick effects or fancy camera angles. There’s no artsy lighting, weird focussing techniques or surrealistic fades. It’s filmed realistically, and as simply as possible for each scene. Given the overall grandeur and epic sense of the story, I think this was the wisest choice Jackson could make. Without feeling grounded, earthy and “normal,” it would fly away.

The music provides a strong second to the realism. There’s very little eerie-ness to the sound track. The themes are grand or sweet, but always simple. The martial Gondorian theme pours enthusiasm into the heroism of the battles; the single poignant violin underscores the valor of the Rohirrim; the lilting Shire theme creeps into Mordor to remind us why it’s so amazing that Frodo and Sam, simple hobbits, are risking everything and suffering so much.

To keep from blithering, I’ll just reiterate what I said in my earlier reviews about the sets and costuming. They’re great. Really, really great. The artists and set designers purposed to create an unashamedly beautiful world. Minas Tirith, the white city, is breathtaking. Literally — I heard people drawing in their breaths everywhere around me in the theatre the first time we saw it. But even Mordor is beautifully awful. It looks the way an evil place should look. As I was sitting through the end credits, I couldn’t help but notice the dozens and dozens of names listed in the categories of “carpenters,” “hammer hands” and “greens” (and on a side note, the “Barad Dur Destruction Lead’s” name is Gray). It drove home a fact that’s easy to forget: Middle-earth itself is one of the story’s primary characters. Hundreds of people, working on this movie, didn’t forget it.

I have to see it again.

(New Line Cinema, 2003)