Ursula K. Le Guin is an anthropologist of people and cultures that might be. Her book Always Coming Home is the clearest example; in it she studies a possible future civilization in northern California, unearthing stories and descriptions of architecture, festivals, healing ways and recipes. But a great many of her science fiction novels and short stories, set in the imagined future of the galaxy-wide Ekumen, are the explorations of a curious, observant mind who is truly able to hypothesize the differences that might make a culture alien to us, as well as the commonalities that can draw disparate cultures together.

Ursula K. Le Guin is an anthropologist of people and cultures that might be. Her book Always Coming Home is the clearest example; in it she studies a possible future civilization in northern California, unearthing stories and descriptions of architecture, festivals, healing ways and recipes. But a great many of her science fiction novels and short stories, set in the imagined future of the galaxy-wide Ekumen, are the explorations of a curious, observant mind who is truly able to hypothesize the differences that might make a culture alien to us, as well as the commonalities that can draw disparate cultures together.

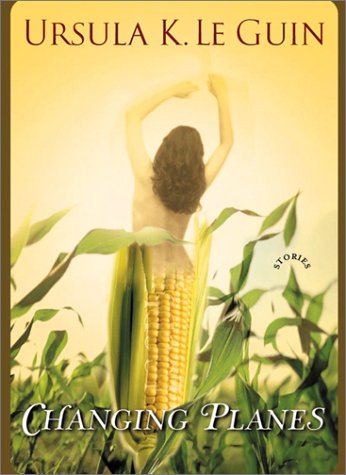

In her newest short story collection, Changing Planes, Le Guin tells us that she’s discovered a new way to reach other possible realities. You don’t have to look far into the future or across space at all, she says. You simply have to be in airport. That’s right. Using “Sita Dulip’s Method” (also the title of the first story), any traveler who is stuck between flights, waiting on a delayed airplane, or otherwise sitting for hours in discomfort and anxiety in an airport, can “change planes.” The strange state of being “between” places in the placeless space of an airport, accompanied by the physical and emotional discomfort, provide the necessary impetus and energy to make the leap from our plane to another one. You can explore an endless variety of other planes, some of them very much like ours, some very different. Le Guin here gives us a series of accounts of her own interplanary travels, as well as those of some of her friends.

In most of these fictional accounts, Le Guin hypothesizes what the world might be like if one or more aspects of what makes us human were different. What if some of us could grow wings, like “The Flyers of Gy”? What if we migrated seasonally, as birds do, and as they do on the plane of the Ansarac? What if we were all able to share our dreams with one another, every night, as they do on Frin? Some of the stories, however, are clearly satire, fictionalized accounts of worlds very much like our own, intended to point to the ridiculousness of our behaviour or the serious consequences of our actions. The funniest of these is “The Royals of Hegn.” Hegn is a plane on which everyone is royal. Everyone can trace their ancestry to one or another royal line, and they spend a great deal of time studying their family trees, when they aren’t talking in genteel tones about dog breeding or gardening. Well, almost everyone. In each Hegn nation, there exist a very few commoners, people who aren’t related to any royal family at all. They are so rare that they are treasured, talked about, followed around and studied. Their tacky clothes are discussed in detail. Their sexual transgressions become national news.

More distressing, and more ominous, is the sharply pointed “The Cleansing of Obtry,” in which two different ethnoreligious groups, the Sosa and the Astasa, live side by side in relative harmony for nine hundred years, even intermarrying and spawning the daughter groups of the Sosasta and Astasosa, until the pressures to become a modern nation spark a series of ethnic cleansings, one group against another, causing hundreds of years of senseless slaughter.

There are obvious parallels here with Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, but I’ve enjoyed Changing Planes far more than Gulliver’s Travels. It could be that I find Le Guin’s modern English easier to follow. Or perhaps the fact that she satirizes current cultures and phenomena makes her stories as funny or poignant to me as Swift’s must have been to his generation.

However, I think it’s more than that. Swift was first and foremost a political satirist. Le Guin, on the other hand, truly has the heart of an anthropologist. She remains genuinely curious about every culture she first imagines, then studies closely. Her delight in the differences between people and her relentless desire to establish some sort of commonality that makes communication possible across race and culture come across as love rather than judgement. Even as she skewers the royals of Hegn and their fascination with their commoners, it’s clear she enjoys the little details about them, like the cheap short skirts that commoner “Chickie” wears. Her story “Porridge on Islac” is about the possible dangers of genetic manipulation, yes. But it’s also about being a traveler in a place you’ve never been, and sharing a bowl of porridge and a moment of communion with a native. As Le Guin tells the story, you can smell the porridge, taste it.

From the opening “Sita Dulip’s Method,” Le Guin’s sense of humor is very much in evidence here, sometimes gentle, sometimes biting. In fact, this may be the most humorous collection of her stories that I’ve read. Eric Beddows’ odd black and white drawings draw out and enhance the humor.

However, I find, as I’ve always found in the past, that the stories that stay with me, that impact me the most deeply, are the ones in which she takes a difference, makes a change in what’s possible for a human, and explores it with a mind both brutally honest and as delicate as an archeologist’s brush. These stories are odd. They don’t seem to have a satisfying conclusion. They leave me unsettled, as if someone took my glasses — glasses I didn’t even know I had — and disappeared with them. “Feeling at Home with the Hennebet” is one such story. The Hennebet are a people who look just like the author, share so many of her tastes and tendencies that she feels immediately comfortable with them. Then, in conversation one day, she discovers that they’re saying things using words she’d use, but meaning something completely different, something she can’t understand at all. Do they have more than one soul? Do they truly reincarnate? In the end, she can’t know, because they are so fundamentally different that their explanations are meaningless to her, as her questions are to them.

In the final paragraph of “Sita Dulip’s Method,” Le Guin says, “The following reports and descriptions of other planes… may induce the reader to try interplanary travel; or, if not, they may at least help to pass an hour in an airport.” I have a airplane trip coming up, and I’ll be spending time between flights in the Phoenix airport. I’m taking this book with me.