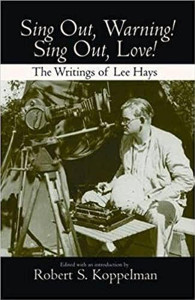

You all recall Mister Lee Hays: the bass singer from The Weavers. He was last seen in the Weavers reunion film Wasn’t That a Time. He passed away shortly thereafter. Robert S. Koppelman, assistant professor of English at Broward Community College and a banjo player and singer, has gathered together a rich collection of Hays’s writings. With these writings and the Weavers’ albums, Lee Hays will live on. His spirit is tangible on these pages. As rough and tumble, as gentle, as opinionated and as caring as he appeared in life . . . so too is he in written form.

You all recall Mister Lee Hays: the bass singer from The Weavers. He was last seen in the Weavers reunion film Wasn’t That a Time. He passed away shortly thereafter. Robert S. Koppelman, assistant professor of English at Broward Community College and a banjo player and singer, has gathered together a rich collection of Hays’s writings. With these writings and the Weavers’ albums, Lee Hays will live on. His spirit is tangible on these pages. As rough and tumble, as gentle, as opinionated and as caring as he appeared in life . . . so too is he in written form.

For the most part, Koppelman has arranged things chronologically. He begins by providing a biographical introduction which places Hays squarely in the left wing of American culture. That’s good, since it’s where most folk singers find themselves. The Foreword, written by Pete Seeger, is affectionate and funny. Seeger notes, “I used to think Lee was just cantankerous. Now I think he was some kind of genius.” Koppelman attempts to prove this — and with a body of work such as Hays provided, it’s not that daunting a task.

“Lee Hays was the very large man with the deep bass voice and wry sense of humor who performed from 1948 through 1964 with the Weavers, the first progressive urban group to popularize folk-style songs…” They lived through, and had their careers affected by, the anti-communist black-list, and they set examples for folk groups to follow. Imagine Peter, Paul & Mary or the Kingston Trio without the Weavers. It’s impossible. Koppelman has an abiding love and respect for Hays, and as you read you understand why.

Part One: the Times includes three sections of writings. “The 1930s: Early Years in the South, Awakening to Left-wing Culture, Organizing the Rural Southern Poor,” “The 1940s: Beginnings of a Performing Career, New York, the Almanac Singers, People’s Songs, the Peekskill Riot, and the Formation of the Weavers,” and “The 1950s: The Weavers, Pop Charts to Blacklist.” These sub-titles pretty much describe the content and context of the writings included therein. They are short editorial articles, longer reminiscences, descriptions of events and people whom Hays knew. His writing is lively, chatty and entertaining. It is never stuffy or holier-than-thou, even when he is desperately trying to make a point.

The early articles find him developing his style, and by the ’40s he’s pretty much got it locked up. Whether telling stories about the development of a folk-song, or providing newsy little biographies of Claude Williams, or telling about the Peekskill riot, he is fascinating to “listen” to. It’s like the tales my grandpa used to tell about the depression and his baseball career . . . chatty, warm, and involving. His articles about the Folk Music Revival . . . yep, there was a revival back then too . . . are must-reads, and his remembrances of Woody, definitive.

Koppelman concludes the collection with a section called “Some Literary Experiments.” These include a couple of stories originally published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine which are kinder and gentler approaches to the mystery genre. Still compelling. Hays was, as Seeger described him, “some kind of genius.” He was also a gardener. And let this poem, sent to Seeger’s wife the year before Hays died, be his epitaph . . .

If I should die before I wake

All my bone and sinew take.

Put me in the compost pile

To decompose me for a while.

Worms, water, sun will have their way

Returning me to common clay.

All that I am will feed the trees

and little fishies in the seas.

When radishes and corn you munch

You may be having me for lunch.

And then excrete me with a grin

Chortling, there goes Lee again.

(After a pause) ‘Twill be my happiest destiny

To die and live eternally.

(University of Massachusetts Press, 2004)