Craig Clarke penned this review.

Craig Clarke penned this review.

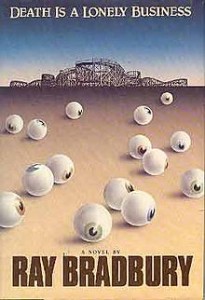

In 1985, over twenty years since the publication of his last full-length work, 1962’s Something Wicked This Way Comes, Ray Bradbury reentered the novel-writing world with the release of Death is a Lonely Business, his foray into a genre dominated by Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and Ross MacDonald — the crime novel.

This book has many layers to it. First, on the surface, it’s a fine noir pastiche. Second, it’s a fictionalized autobiographical portrait of Bradbury himself in 1949, in the early days of his publishing.

The narrator of Death is a Lonely Business is a writer living in Venice, California, where the local carnival pier is being demolished. He discovers the body of Willie Smith, underwater and trapped in a disused lion cage. Then a strange shadowy figure begins appearing in hallways and outside windows at night and the number of murders increases.

He teams with local police detective Elmo Crumley — reluctantly, at first, on Crumley’s part — to solve the case. The only clues they have are the writer’s intuition, articles that go missing from the deceased’s residences, and a blind man’s keen sense of smell.

Our hero is especially interesting as a portrait of Bradbury himself in 1949. The naive, plump, 27-year-old writer, who is just becoming successful, inspires immediate identification from fans of the master’s work. We already like the author, so we immediately root for his doppelganger. I especially enjoyed the personal clues Bradbury laid within the story, some of which it takes a brave person to lay bare in print. But they work to gain our sympathy, which is quite necessary; in the beginning the writer is painted — whether deliberately or not — as a somewhat unsympathetic character prone to outbursts.

The other characters are just as fascinating: Crumley, the cop who just happens to also be a writer; Fannie, the 380-pound sedentary soprano; A.L. Shrank, the psychiatrist with the downbeat library; Cal, the incompetent barber with the ragtime past; John Wilkes Hopworth, the ex-silent film star who still pines for former love Constance Rattigan, his former costar who is dead set on not becoming Norma Desmond from Sunset Boulevard (“That dimwit Norma wants a new career; all I want most days is to hole up and not come out.”); and Henry, the blind man, who is the only one who can identify the killer — by his smell.

Death is a Lonely Business is Ray Bradbury’s entry into the noir genre, done in his inimitable style. He plays with the conventions, but since he so obviously loves the genre, this is easily forgiven — embraced, even — because the end result is, simply put, a fine addition to the canon.

(Alfred A. Knopf, 1985)