Book cover art can be a tricky topic. Publishers insist they take many things into consideration when choosing cover art. They balance things like branding, marketing, genre identification. They consider such factors as target audience, and author recognizability from book to book. Authors have been known to cry over horrible book covers. Lots of authors.

Book cover art can be a tricky topic. Publishers insist they take many things into consideration when choosing cover art. They balance things like branding, marketing, genre identification. They consider such factors as target audience, and author recognizability from book to book. Authors have been known to cry over horrible book covers. Lots of authors.

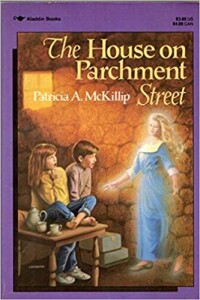

I start this review of this 1973 novel with this mention of covers because the cover of the Aladdin Books 1991 edition (after the 1978 printing) is problematic. Take the original cover by the artist of the interior illustrations, Charles Robinson. While not my favorite cover ever, it’s at least consistent with the interior. There’s nothing too definitive to give away the exact age of our protagonists, Carol and Bruce. But the paperback cover leaves no doubt these are children. Not teenagers, not “young adults,” but children. So when Bruce’s father indicates his son was seen smoking, and tells him he’s old enough to be making his own decisions about such things, it’s a bit of a shock, from a reader’s viewpoint. Since Bruce’s age is not even obliquely mentioned until near the end of the book (no portion of plot will be spoiled if I reveal he’s fourteen), many of the other issues McKillip tried to have her characters address in this story become more clear. Unfortunately, not clear enough.

There’s no doubt this book is intended for younger audiences. It might best fit the sensibilities of what’s now commonly referred to as a middle grade novel, but it doesn’t have anything close to the depth or complexity — of language, of situation, of characterization — most modern readers expect of a young adult novel.

I’m not sure the term “middle grade” was even in use in 1973. McKillip herself was only about twenty-five years old when The House on Parchment Street was published. It may have been a ploy by the publishers to have juvenile-looking main characters depicted in the interior and exterior art. Perhaps their target market was librarians, parents, and teachers; those who would purchase this as a story for children, not the children themselves. It certainly doesn’t help pull the characters in focus. While our protagonists do struggle with issues of self-identity and maturation, everything is as fuzzy as the illustrations. The kids’ dialogue and actions are unbelievable, even tedious. The dialogue and behavior of the adults is even worse. Almost, the appearance of ghosts and the mystery and history of Parchment Street and its long-gone residents is so negligible, it’s hardly worth mentioning, other than to firmly place the story in a speculative genre.

While McKillip’s writing here can be lovely, and some of the detailed descriptions of minutiae are quite interesting, the characters, the storyline, the resolution are all rather uninspired in execution and delivery. This book might be mildly interesting to some audiences as old as nine or ten, but I think you’d do much better slipping your young reader friends some Forgotten Beasts of Eld or something from McKillip’s excellent Riddle-Master series instead. The cover art sure is better.

(Aladdin Books, 1978)