The Forgotten Beasts of Eld was the first book by Patricia A. McKillip that I ever read. Two things struck me about it: it was different than any other fantasy I had read to that point, most of which were in the high-minded, seriously heroic mode, but written in “realistic” prose; and it was funny. I didn’t know fantasy could be funny. This was not the almost-tongue-in-cheek of L. Sprague de Camp or of Gordon Dickson’s dragon books, nor the edgy satirical vision of Fritz Leiber, but the result of sharp, contemporary dialogue that betrayed a sympathy for slapstick that came out of nowhere and left you gasping — think of it as the Marx Brothers meet The Fellowship of the Ring.

The Forgotten Beasts of Eld was the first book by Patricia A. McKillip that I ever read. Two things struck me about it: it was different than any other fantasy I had read to that point, most of which were in the high-minded, seriously heroic mode, but written in “realistic” prose; and it was funny. I didn’t know fantasy could be funny. This was not the almost-tongue-in-cheek of L. Sprague de Camp or of Gordon Dickson’s dragon books, nor the edgy satirical vision of Fritz Leiber, but the result of sharp, contemporary dialogue that betrayed a sympathy for slapstick that came out of nowhere and left you gasping — think of it as the Marx Brothers meet The Fellowship of the Ring.

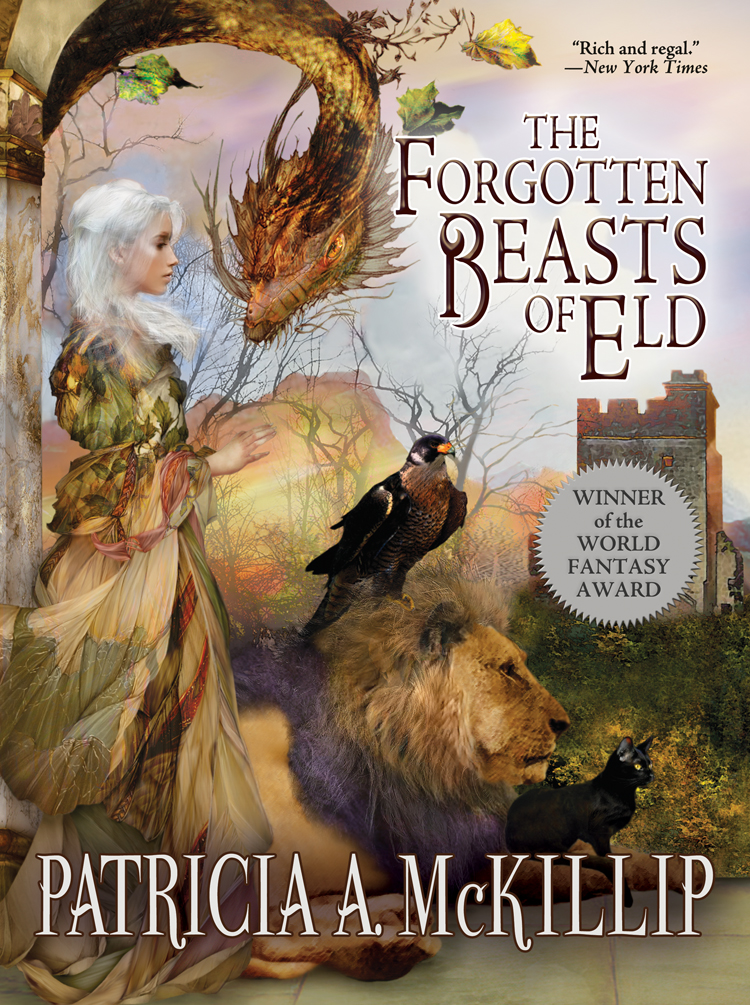

Sybel comes from a line of wizards who have the ability to call creatures to them. Her father and grandfather have collected a menagerie of near-mythical beasts, the subjects of bardic lore, with magical abilities of their own. Sybel, living alone in her house on Eld Mountain, steals books from other wizards and discovers references to a fabulous bird, the Liralen, that no one has ever managed to call. That becomes her project, until she is interrupted in her solitary existence by the appearance of Coren of Sirle with a baby in his arms: Tamlorn, the son of the queen of Eld, and, Coren thinks, of his brother, killed in the battle just fought between Sirle and Eld. Sybel accepts the child, who grows up among the animals in the house and the forests on the mountain; when Tamlorn is twelve, Sybel, for reasons that are largely opaque, calls Drede, king of Eld, to her house. Drede is Tamlorn’s father, and Tamlorn finally goes off with him to live in Eld and learn the ways of men. The way is set for a poignant and bittersweet tragedy.

This is another one of those magical creations by McKillip that ostensibly fits into the young-adult fantasy mold but holds great wealth for adult readers as well. The themes are those that underlie the body of McKillip’s work: love, honesty, and the difficult and confusing business of growing into maturity. In many ways, this one sets the tone for later works: the diction is elliptical; dialogue slides effortlessly between sharp, off-the-wall responses and direct, uninflected poetry; magic is an assumption, evident as much in the telling of events as in anything the characters do; and the characters themselves are deftly and subtly drawn. And, as is usually the case, McKillip manages to pack a huge amount of story into a fairly slim book.

One of the magical things about this one is that it reads like a fairy tale. I’ve only seen a couple of authors pull this kind of thing off, and McKillip is one of them. The story of Sybel, Coren and Tamlorn has much the same quality as the best renderings of folk and fairy tales recorded by the Grimms or created by Andersen, fleshed out into a novel with real, living characters who never lose that feeling of otherness while behaving like normal human beings. (The other who comes to mind is Steven Brust in Brokedown Palace, although his manipulations of the form are equally masterful, but more readily apparent.)

And, as is often the case with fairy tales, the happy ending is also bittersweet. To go anywhere, you must leave where you are, no matter how sad that parting. Loss is part of life, and learning to let go is essential. The depth in this story is provided by the graphic illustration, in Sybel’s search for the Liralen and her encounters with Blammor, the embodiment of everything we fear, of the idea that to find our worst enemy we need only look in the mirror. And yet implicit in this is also the understanding that we must let go of that realization, as well.

If you are familiar with McKillip, this is a good one to read (or reread — it’s on that list). It’s a great starting point for a magnetic and magical writer, and it’s a good way to bring her other works into sharp focus. It’s also a terrific book all by itself.

(Atheneum, 1974)

Tachyon Press will be putting out a new edition on the Autumn Equinox with a foreword by Gail Carringer on why The Forgotten Beasts of Eld is her perfect desert island novel. It would get a World Fantasy Award, the first of three to date.