A storm is coming, but the winds are still,

A storm is coming, but the winds are still,

And in the wild woods of Broceliande,

Before an oak, so hollow and old

It look’d a tower of ivied masonwork,

At Merlin’s feet the wily Vivien lay…

Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King”

We’ve reviewed over fifty novels and collections that have some mention of Merlin in them. This does not count the many works of non-fiction that make reference to him. The ancient cyfarwydds, the Welsh Taleweavers or storytellers, who first mentioned him have certainly made him one of the most enduring characters in fiction today. From the lighter, more warm version of him in T.H. White’s The Once and Future King to the quite mad version of him in Robert Holdstock’s Merlin’s Wood, or The Vision of Magic, Merlin haunts Celtic myth and storytelling as none other, including Arthur Pendragon. He is something far beyond mortal, and quite beyond our understanding; he is truly the defining character of Arthurian literature. For well over a thousand years, storytellers have sought to explain Merlin and what he did in creating Arthur and his nation. This anthology adds several choice tales to that attempt.

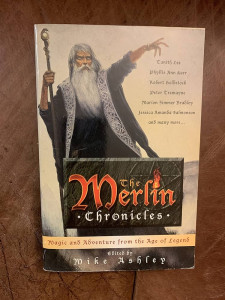

The Merlin Chronicles includes superb tales of magic and adventure, most specially written for this volume, ranging from short stories to complete novellas — including a Robert Holdstock piece, “Infantasm,” that I can’t find anywhere else. Their common theme is the dark side of the Arthurian world, the realms in which Merlin and the magic of the old beliefs clash with what Arthur thought he was creating. If you thought that the Excalibur film was cool, you’ll love The Merlin Chronicles! Just note the list of writers herein: Marion Zimmer Bradley, Maxey Brooke, Vera Chapman, Madalen Edgar, Esther M Friesner, Colin R. Fry, Robert Holdstock, Phyllis Ann Karr, Tanith Lee, Charles de Lint, William Morris, Dinah Maria Mulock, H. Warner Munn, Jennifer Roberson, Theodore Goodridge Roberts, Jessica Amanda Salmonson, Darrell Schweitzer, Emile Souvestre, David A. Sutton, Peter Valentine Timlett, Peter Tremayne, and E. M. Wilmot-Buxton! And the tales are as good as one would expect given this group.

“Dramatis Personae: A guide to Arthurian characters” is given by Mike Ashley to lead off the volume, useful even if you know the characters, as his notes are concise and help you sort out many of the minor players — such as Ogier, a Danish knight in the service of King Arthur who was later intertwined with both Avalon and the evil deeds of Morgan la Fay. Ashley’s summation of Merlin includes the intriguing idea that Merlin was “probably more a title or office than a personal name.” And his inclusion of alternative spellings — Merrillin, Merdyn, and Myrddin in the case of Merlin — in addition to the most common name spelling is very nice.

But the fiction is why you’ll be picking up this anthology. Savor “Merlin Dreams in the Mondream Wood,” Charles de Lint’s excerpt from his Spiritwalk novel (also reprinted in his new collection Waifs & Strays) which postulates a house in Ottawa that surrounds a magical wood in which has the very old Merlin — not looking at all old — sleeps within an oak because the love of a mortal female has trapped him there. (If you like this charming sliver of a tale, go read his Moonheart and Spiritwalk for all the roots and branches of the Tamson House tale.) “Infantasm” by Robert Holdstock is a horror story in which Merlin creates a shambling “semblence of humanity from that which is not human,” clearly a play off the various transformations that take place in The Mabinogion. Read it with the lights on — this one ends very, very badly. “Midwinter,” a David Sutton-penned tale, adds interesting details to what happened to Merlin after Arthur and Camelot had collapsed about him. Not surprisingly, a mysterious young woman figures into the tale.

You might by now be getting the impression that Merlin is less than favourably viewed by most of the writers here in The Merlin Chronicles, and you be more or less correct; the Merlin in “King’s Mage,” a Tanith Lee tale, causes great good, which in turn causes great harm, as nothing is pure in his magic. More harmless is the Merlin in “Dream Reader,” an excerpt from Jane Yolen’s Merlin’s Booke, which treats us to a look at “Merillin the Hawk,” as Yolen calls him, and how this callow youth came to be the powerful, troubled Merlin. And like so, so many tales regarding Merlin, who he is is far less worthy of note than what actions will occur as a result of him.

There’re dozens of other tales in The Merlin Chronicles, but I won’t detail them here. Suffice it to say that there’s enough reading here for many a cold winter’s night. Some will be to your liking, some I wager won’t be. This book is, for now, out of print, but used copies can be found online.

(Raven Books, 1995)