Ahhhh, come in. Let me set aside Catherynne M. Valente’s new novel The Orphan’s Tales: In the Night Garden – lovely take on The Arabian Nights motif with elements of fantasy and horror in it.

Ahhhh, come in. Let me set aside Catherynne M. Valente’s new novel The Orphan’s Tales: In the Night Garden – lovely take on The Arabian Nights motif with elements of fantasy and horror in it.

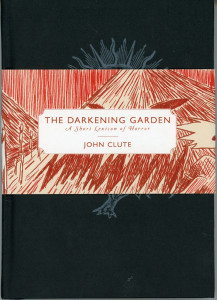

What’s that on my desk? Oh, it’s just an exquisite little book that came in for review. It’s an excerpt of sorts form John Clute’s forthcoming look at horror. I see that you’re puzzled, as you know him from the The Encyclopedia of Fantasy and The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, two massive works that are heavy enough to be used as flower presses if need be! But at a very compact one hundred and sixty-two pages, The Darkening Garden is an appetizer, a wonderful small taste, of what’s in store.

A Green Man staffer once said, while musing over another reference work we got for review, that ‘good reference guide is as much magic as a properly made stew with its melange of flavours, or hearty bread with a nose-tickling aroma that makes your mouth water!’ I certainly would agree with that thought as I, as much as I use the internet these days for research when writing reviews, still love using a reference work written in ink, with a legible font, on good paper, in a book with a decent binding (pay attention to those criteria as they’ll figure in to this review) every bit as much as I like reading a particularly superb piece of fiction. Despite their age, I still often pull out either The Encyclopedia of Fantasy or The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction to look up an author or, more often, a motif, e.g., ‘wainscot societies’ or ‘urban fantasy’. Both works remain among the best looks at their respective genres that have been done to date in large part because Clute likely knows more about these intertwined genres than anyone else involved in writing reference works on these genres!

Rumor has that John Clute has begun work on an electronic version of both Encyclopedias. No word on when it will be available. The publicist who told me this at St. Martin’s is now long gone and apparently no one there knows when the project will be initially up. Whenever it’s done will be a happy day indeed!

I asked Cheryl Morgan, editor and publisher of the Hugo Award winning Emerald City Web site, who is a friend of Clute’s, to say a few words about him. Here’s her reply:

John Clute is perhaps the only person who has succeeded in making a living as a science fiction critic outside of academia. Many people, of course, make money from sf criticism, but for the vast majority of us this income is merely a welcome adjunct to a more reliable source of funds. While Clute has written some well-received fiction, criticism is his main career. He has written large numbers of reviews, essays and obituaries, several books, and most importantly two major encyclopedias. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (with Peter Nicholls) and the Encyclopedia of Fantasy (with John Grant) both won Hugos and are regarded as some of the most important reference works in the field. Their success is due, in no small way, to Clute’s passion for getting things right. Other people may rely on the likes of Wikipedia for data, but Clute is convinced that reliable information does not grow organically, it must be mined for through determined and relentless research. This dedication produces reference works of rare quality that their users can have great confidence in. And the good news is that the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction is due to go online, where it can be more easily updated, sometime in 2007.

Canadian by birth, Clute has lived much of his life in London. He and his wife, Judith, inhabit a pleasant, book-filled apartment in Camden Town, a part of the city frequented mainly by punks, goths and other species of fashionable teenagers. Their residence has become a focal point for the science fiction community and their generosity as hosts has been recently chronicled in the festschrift book, Polder.

Thanks Cheryl!

I am not, by any stretch of the imagination, a hard-core horror fan. Oh, I’ve read some Stephen King (particularly his short stories, which are superb), a bit of Clive Barker, and Raymond Feist. But I have read lot of dark fantasy that has horror tropes in it, such as Christopher Golden’s The Myth Hunters and The Borderkind, Charles de Lint’s Mulengro, Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes, and Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing to name but few of this ilk, so I was rather curious about the idea that Clute had created a short lexicon of horror that defined the essential elements of this genre.

(Digression – genres do count. Don’t ever let the skeptics get away with claiming otherwise. They help define a book and help potential readers in a better than merely good bricks and mortar bookstore find it. Do you go into the romance section of your local Borders? I don’t. Do you scan the shelves of genres you’re interested in? I do. Indeed I found a lovely mystery series I had never heard of, Deborah Grabien’s Haunted Ballad novels, in a local bookstore that had one copy on the shelf. I requested a review copy of all the novels from St. Martin’s who graciously sent them. Indeed they are on my Best of 2006 list!)

I don’t recall us reviewing anything from Payseur & Schmidt before, so I was pleased when this elegant little book showed up in the Green Man mailroom where Wendell, our temp in the mail room, pointed it out to me. Physically, it’s best described as a hardbound chapbook from a era long gone – if printers were that good in those days – that one might see in a really high-end used bookstore. It’s only 164 pages in length, including the colophon at end which you must read, and amply illustrated with black and white drawings by thirty artists (see that colophon for how they were picked). And printed in just 500 copies! (I have the 459th one.) Thirty entries follow Clute’s succinct introduction, explaining both the title (lovely as it is for echoing for Diane Purkiss’ At The Bottom Of The Garden: A Dark History of Fairies, Hobgoblins, and Other Troublesome Things, since horror creatures are often very troublesome ) and his reason for writing this lexicon. Keep in mind that unlike both the Encyclopedia of Fantasy and the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, where the entries therein were very much a group effort with myriad contributors, this is the effort of Clute alone. An effort matched by the superb work of Payseur & Schmidt in creating a reference work written in ink with legible type faces (Gill Sans and Adobe Caslon Pro to be precise) on good paper in a book with a decent binding.

So what do we have? Let’s look at an entry as reprinted from the publisher’s website:

CLOACA

It is not hard to understand how essential the portal is to the architecture of any fantasy in which a protagonist moves from one world to another: to envisage a wardrobe whose mothballs are butterflies is surely the easiest way for an author to figure travel afar, anew. Farah Mendlesohn’s arguments about the nature of the Portal — in Chapter One, “Portal Fantasy”, of her Rhetorics of Fantasy (Wesleyan University Press, 2007) — constitute a thorough exploration of the use and structural implications of the device. At the same time, it should not be hard to understand that the Portal is peculiarly well fitted to Fantasy precisely through its isomorphism — in storytelling terms — with that escape from prison so central to the genre (see free fantastic). Tales of horror, on the other hand, as demonstrated in almost every single entry in this lexicon, do not normaly involve travel to a secondary world, nor can they be understood as escapes from the world. What might seem exceptions — David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus (1920), for instance, or Stephen R Donaldson’s first Thomas Covenant trilogy (all volumes 1977) — tend to be novels whose encompassing difficulty creatively darkens any sense of the moral clarity — the sex without semen — of escape. Novels like these intrinsically mutate the moves of genres like Horror and Fantasy, and in that sense operate at the forward edge of the fantastic: where change threatens the ideas of order. But this does not mean that Horror is about the freedom to leave; for it is not.

So: what is defined as Portal in Fantasy does not exist in Horror: so the term Cloaca is applied here to semblances of Portal when such are uncovered. If entering a Portal can be likened to swimming with the tide as upon a quest, then entering a Cloaca can be likened to swimming upstream like a gaffed fish: hooked. The Cloaca is a parody of the Portal: an extremely bad joke (such being common in tales of Horror) about the true nature of the world. The term is visceral, it allows a strong inference of deep unpleasantness ahead. Almost always, Cloacas are lesions in the thickening of the world towards the moment of truth, when the rind of things is peeled. They are indentations in the rind which hint falsely of egress. then sully. They are indistinguishable from the bad place: the house built with cavities beneath the cellar, or the bottomless swamp, or some labryrinth which strangles Ariadne: the omphalos that leads to the blank stone exitless stair to the underworld. The eponymous house in Stephen King and Peter Straub’s Black House (2001) is a Cloaca, a place out of the basement anus of which an M C Escher tangle of stairwells leads the protagonists downwards to the black tower. The Congo in Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” (1899 Blackwood’s Magazine) is cloacal.

In the end, the message is clear enough. If the omphalos into the body of the earth is in fact Cloaca, then the world is surely diseased, and we are all up shit creek without a Portal.

Clute’s language is every bit as mythopoeic as Catherynne M. Valente’s is in The Orphan’s Tales: In the Night Garden. Clute doesn’t so much define a topic, a trope, a meme if you will as create a story about it. Indeed that is only proper as stories are what we’re concerned with. The Darkening Garden succinctly defines what horror is and is not as envisioned by Clute. I’d be extremely interested to see what would result if both the Encyclopedia of Fantasy and the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction were distilled down to this elegant level of compactness! Though it might only take you a winter evening to read, it made me grab Ygggdrasil, my iBook, to look up many of his references as there’s years of reading cited in The Darkening Garden!

(Payseur & Schmidt, 2006)

[Update: The Encyclopedia of Fantasy and The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction are available online.]