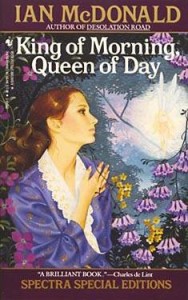

Today, I picked up King of Morning, Queen of Day again just to refresh my memory before writing this review. After all, it doesn’t do to refer to a book’s main character as Jennifer if her name is actually Jessica. But my quick brush-up turned into a day-long marathon of fully engaged, all-out reading. I’ve been on the edge of my seat, I’ve been moved to tears, I’ve laughed, I’ve marked passages that I want to quote.

Today, I picked up King of Morning, Queen of Day again just to refresh my memory before writing this review. After all, it doesn’t do to refer to a book’s main character as Jennifer if her name is actually Jessica. But my quick brush-up turned into a day-long marathon of fully engaged, all-out reading. I’ve been on the edge of my seat, I’ve been moved to tears, I’ve laughed, I’ve marked passages that I want to quote.

Have I interested you enough to offer you a brief overview?

The book begins in 1913 with a girl named Emily Desmond. A typical Victorian teenager in most ways, bored with school and poised on the brink of sexual self-discovery, Emily possesses one atypical trait. She can tap into the “Mygmus,” the mythic subconsciousness that lies deep within the entire human race, and bring into physical life the things she finds there. From repeated reading of Yeats and her own feverish imagination, she conjures up for herself a fairy lover to take her away to a glorious new world, wherein she discovers that anything she imagines can come into reality.

Things go seriously awry for Emily, however. Hannibal Rooke is a Victorian man of science who follows the development of Emily’s remarkable trait (which he calls mythoconsciousness) in Emily herself and down through her descendants. He tells her, “Hell is not other people. Heaven is other people. Hell is oneself. Forever and always, oneself. Self. Self. That has been the entire motive of your. . . I hesitate to call it life. Existence, since you gained the ability to be and do exactly what you liked.” Emily ignores Dr. Rooke, and stretches out her greedy hand for the one thing she has created that has a life independent from hers — her daughter Jessica.

Fortunately for Jessica, she has inherited an aspect of her mother’s gift, and early in her childhood she unwittingly calls into being from the Mygmus two protectors, The Watchman and the Spinner of Dreams. Named Tiresias and Gonzaga, these two wander the country in the guise of old tramps, trapping and sealing off “phaguses,” pieces of the Mygmus that Emily has released into the world to find and bring Jessica to her. In a final showdown, Jessica confronts Emily and refuses to join her in rejecting this world for a life of self-gratifying fantasy.

But it isn’t over yet. Jessica may have repudiated her mother, but she cannot close the door that Emily has opened between our world and the Mygmus. Phaguses continue to bleed through and wreak havoc as they fulfill the dreams and nightmares of anyone they encounter. The task of closing the rift falls to Jessica’s granddaughter, Enye. Armed with mythoconsciousness, a Japanese katana, and a drug created by Dr. Rooke called Shekinah, Enye patrols the night, finding phaguses and destroying them, sending them back to the Mygmus. Enye learns, however, that phaguses will never stop coming until the open wound between the two worlds is healed; and the wound is Emily herself.

This book is full of remarkable, memorable images. As just one example, Tiresias and Gonzaga are beautifully conceived as eccentric tramps who have more about them than meets the eye. Tiresias carefully hoards a pair of spectacles in a greasy chamois and is given to outbursts of schizophrenic rambling. Gonzaga mutters in anagrams and roots around in refuse piles for odd bits of junk and strips of bark and bird feathers, which he keeps in a decrepit backpack. In the blink of an eye, however, Tiresias’ spectacles become glasses through which he can see the mythlines, pathways of the phaguses, and Gonzaga weaves his scavenged oddments into fetishes and spells of glinting power.

King of Morning, Queen of Day did present me with one serious obstacle, however. I almost set it down unfinished when I first read it. The book is divided roughly into thirds, covering the stories of Emily, Jessica, and Enye consecutively. Unfortunately, the first story has absolutely no likable characters in it. Emily is shallow, whiny, and irritating, and the secondary characters are flat and two-dimensional. The characters in Jessica’s story are much better, and the story is intriguing. Enye’s story is enthralling, the characters deeply satisfying. Unfortunately, one can’t simply skip the first story, as the entire book builds cumulatively from Emily’s first descent into selfish fantasy. But readers of this review will have an advantage I lacked: someone telling them to persist through Emily’s story. It will get better.

Fans of Charles de Lint will delight in Enye’s sword-wielding encounters with pookas and other mythic creatures in the back alleys and underpasses of modern Ireland. Anyone who has read Robert Holdstock as well as de Lint will certainly find ley lines of similarity between McDonald’s “phaguses,” Holdstock’s “mythagos,” and de Lint’s “numena.” Like his fellow authors, McDonald also asks serious questions about our modern, civilized world, which seems so stripped of the numinous. In King of Morning, Queen of Day, Dr. Rooke says, “Where is the mythic archetype who will save us from ecological catastrophe, or credit card debt? Where are the Sagas and Eddas of the Great Cities? Where are our Cuchulains and Rolands and Arthurs? . . . Where are the Translators who can shape our dreams and dreads, our hopes and fears, into the heroes and villains of the Oil Age?” I would say that, by writing this book, McDonald has partly answered his own question.

(Bantam Books, 1991)