Even before the advance reviewers’ copy of this book arrived in the mail, I remarked in the staff break room, “Of course, I already know what I’m going to say in my review. ‘This new anthology from the inimitable editing team of Datlow & Windling is fantastic, and everyone should darn well buy it and read the entire thing as soon as it hits the stores.'” Rather rash, sight unseen, no?

Even before the advance reviewers’ copy of this book arrived in the mail, I remarked in the staff break room, “Of course, I already know what I’m going to say in my review. ‘This new anthology from the inimitable editing team of Datlow & Windling is fantastic, and everyone should darn well buy it and read the entire thing as soon as it hits the stores.'” Rather rash, sight unseen, no?

Except it’s true.

While Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling didn’t write the wonderful stories in the more than twenty anthologies they’ve brought us over the years, they still deserve our first praise and gratitude — without their expertise and unflagging search for new stories being written in corners and playas all over the world, we’d never get to read so much that is “counter, original, spare, strange. . . fickle, freckled (who knows how?) with swift, slow, sweet, sour, adazzle, dim.”*

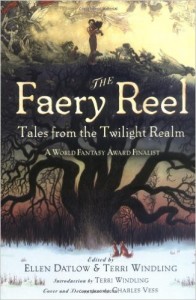

For example, in this new anthology, The Faery Reel, we have seventeen stories and three poems by authors whose work I’ve been reading with delight for years, and by authors I’ve never heard of before. The faery folk in these pieces are urban and tough, or ancient and eerie; they may be silly or deadly. Some are silly and deadly. Some of them come from the tengu and kitsune legends of Japan (“Tengu Mountain” by Gregory Frost and “Fox Wife” by Hiromi Goto). There’s one here based on the Filipino faery tradition (“The Night Market” by Holly Black), and one set in the landscape of Australia (“The Shooter at the Heartrock Waterhole” by Bill Congreve).

It almost goes without saying that the tone from story to story varies wildly — this is an anthology, after all. Some of the fey folk here I recognize and love. Others make me recoil, or shake my head indignantly and mutter, “faeries are NOT like that!” Some of the stories make me laugh, like “The Oakthing” with its solid farm people and their practical approach to their fey neighbor, or the sly Asian humor in “Tengu Mountain.” Others make me solemn, like “De la Tierra” by Emma Bull, with its ominous warning that we are driving the magical out of our world, or even deliberately seeking it out to destroy it.

“The Faery Handbag” by Kelly Link has me solemn and laughing by turns. The main character, Genevieve, has a grandmother, Zofia, who tells stories with the combined pathos and rollicking fun of Isaac Bashevis Singer. Genevieve can never tell if Zofia believes her own stories or is pulling Genevieve’s leg. Zofia won’t say. In fact, she begins her stories by saying, “I know no one is going to believe any of this. That’s ok. If I thought you would, then I wouldn’t tell you. Promise me that you won’t believe a word.” Genevieve and her friend Jake laugh and raise their eyebrows. But when first Jake, and then Grandmother Zofia, disappear from Genevieve’s life, she finds herself wanting to believe that there really is a country called Baldeziwurlekistan in her grandmother’s handbag, and that she’ll find them there some day.

I can’t say that I have a favorite among all these stories. Some days I like the realistically rowdy little girls in Ellen Steiber’s “Screaming for Faeries” best. In other moods, I wish I could hear Charles de Lint sing his “The Boys of Goose Hill,” which he claims he wrote to go to the tune of “The Meet was at Matthews,” a traditional Irish song. And most days, I really really try not to think too much about the novel Delia Sherman claims she’s writing to complement the story “CATNYP,” with its wonderfully whimsical library. You know how it goes — you get all excited about some book an author you love is writing, and three years later they’re still writing it!

But there is one story that keeps surfacing in my mind again and again. It’s eerie and poignant, and leaves me with the helpless longing that always, for me, means I’ve seen something fey. It’s Jeffrey Ford’s “The Annals of Eelin-Ok.” When I started it, I thought it was going to be light-hearted and childlike. There are certain faeries, says Ford, called the Twilmish. They are brought into existence whenever someone builds a sandcastle on the beach, and they live in that sandcastle so long as it stands. When it crumbles under the tide, they go with it. Doesn’t that sound like a lovely bedtime story to tell a small child? But then Ford goes further. He presents in full the contents of the journal of one Twilmish, a man named Eelin-Ok. We read of Eelin-Ok’s excitement and confusion as he is suddenly thrust into life. We share his adventures on the beach and learn to love his faithful pet, a sand flea whom he names Phargo. Eelin-Ok falls in love, then loses his love to the sea. And finally, as he watches the tide coming closer and closer to the walls of his castle, he realizes that he is going to die soon. I found myself choking on a lump in my throat as I read his final words.

“The waves have breached the outer wall and the sea floods in around the base of the castle. . . ‘What does it all mean?’ I have always asked. ‘It means you’ve lived a life, Eelin-Ok.’ I hear now the walls begin to give way. I have to hurry. I don’t want to miss this.”

Wonderful stories and poems, enough in themselves. But this is an anthology from Datlow and Windling. So, in addition, we have here an introduction by Terri Windling, in which she gives a brief (!) overview of the influence of Faerie on literature, music and the popular press over the years, and a listing on the back few pages of “further reading”: novels, story collections and faery folklore for those of us whose appetites may have been whetted (or who are always starved for more books about faeries). “Further reading” lists of this sort are one of the first things I look for in anthologies. Not only do I thrill to make use of them, they also indicate that the editors truly love their field and can’t get enough of it. Datlow and Windling just can’t bear to leave their readers without shoving a final pile of books into their hands.

(Viking, June 2004)

![]()