A scholar once suggested that fairy tales are the collective dreams of the people. They definitely feel that way. And not just daydreams, either, although some of them are — “I may be living with a cruel stepmother now, but I’ll run away some day and marry a handsome prince, see if I don’t!” Most fairy tales; however, are riddled all through with images and sequences that could come straight out of sleep’s web of surreal pages. Animals who walk up to you and ask you to cut off their heads. Houses that stand on chicken legs. Combs that start to bleed when you touch them.

A scholar once suggested that fairy tales are the collective dreams of the people. They definitely feel that way. And not just daydreams, either, although some of them are — “I may be living with a cruel stepmother now, but I’ll run away some day and marry a handsome prince, see if I don’t!” Most fairy tales; however, are riddled all through with images and sequences that could come straight out of sleep’s web of surreal pages. Animals who walk up to you and ask you to cut off their heads. Houses that stand on chicken legs. Combs that start to bleed when you touch them.

But as everyone knows, you almost never dream the same dream twice. In the same way, fairy tales have been changing throughout the centuries, picking up images and people everywhere they’ve wandered. And like dreams, old images with long-forgotten meanings in the stories have taken on new meanings for new listeners, generously — but also mercilessly. They’re still doing it. And some of today’s most imaginative writers are dreaming them in new dreams, spinning them into the web again.

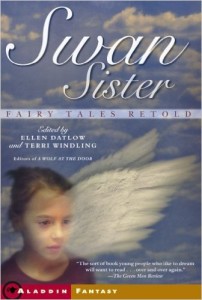

Swan Sisters is a collection of “retold fairy tales” for young people by writers like Jane Yolen, Tanith Lee, Neil Gaiman, and Lois Metzger. There are thirteen tales in all (now there’s an auspicious fairy tale number for you!), and they are all “new,” in that they’ve never been published before, in magazines or whatnot. But they’re also timeless, shaped on the old, old bones of the grandmothers of storylines, peopled with the earliest characters we remember.

We have here, for example, “Little Red and the Big Bad,” by Will Shetterly, which begins this way:

“You know I’m giving you the straight and deep ’cause it’s about a friend of a friend. A few weeks back, just ‘cross town, a true sweet chiquita, called Red for her fave hoodie, gets a 911 from her momma’s momma.”

Once upon a time, a few weeks back. Is the fine looking beastie boy on the corner the Big Bad he thinks he is? You’ve met him. What do you think?

And then there’s “Inventing Aladdin,” a story-in-a-poem by Neil Gaiman, in which he shows Scheharezade going through her daily life, seeing big jars in the street market, buying sesame seeds, and using these little things to spin the stories that will keep her head on her shoulders, night after night. Gaiman says he wants this story to ask questions about how storytellers get their inspiration. I couldn’t help noticing Scheharazade’s sister, who sits on the end of the bed and asks for the stories, prompting, “And then what happened?” How many of us would find the words to tell our stories if someone didn’t ask us for them?

Some of the stories here take just one or two ideas from an old tale and put them in a new story, in a modern setting, like Lois Metzger’s “The Girl in the Attic,” in which a monstrous witch changes into a kind mother when her stepdaughter, who has isolated herself in grief and anger, learns to see things as they really are. Or “My Swan Sister,” by Katherine Vaz, which feels the most like a dream of all the stories here, even as it walks on the broken glass of bleak tragedy. “My sister, Rachel, was born wrong,” says the narrator. “There was a mistake in every cell of her body … ‘She’s our little swan,’ said my mother. Rachel was wild and beautiful and seemed ready to fly away.”

Other stories in the anthology, such as Gregory Frost’s “The Harp That Sang” or “The Children of Tilford Fortune” by Christopher Rowe, use all the traditional characters and settings — farms, harps, bards — and plot devices to create fairy tales that look just like the ones we grew up reading in the old books, until you look closer and notice that certain things are different….

My favorite of these stories, however, manages to take elements from the old world and the new and place them side by side without changing either. In “Greenkid,” Jane Yolen tells the story of Sandy, a young teenager in Massachusetts who likes to go bird watching and manages to coax the beautiful new girl, Merendy, to go with him. It’s true love, he thinks, until a little boy with light green eyes and light green gums toddles out of the trees one day, comes home with Sandy, and tries to charm him for Merendy’s name.

But no matter where or when the stories are set, or the language they’re told in, the impression that comes across again and again is their freshness, the way they make everything look new. They feel like stories I’ve heard before, but I could read them all again. And I will.

![]()

“Who knows? Maybe three hundred years from now groups of writers will still be telling these stories. We hope so. Because there will always be readers who don’t outgrow their love of magic.” — from the introduction

Obviously, school and public libraries will want to have Swan Sister in their collections, as well as the earlier book in this series of tales, A Wolf at the Door. But this is also the sort of book young people who like to dream will want to read, and maybe to own, to read over and over again. Adult dreamers will like it, too. Although all the main characters are young, their stories are ageless.

(Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 2003)