“Wolf Moon is an old favorite of mine. I remember at the time I started to work on it that I wanted to write a small story in a high fantasy setting. Worlds didn’t need to be saved. The characters weren’t required to go on arduous quests. But the events of the story would still have great import upon the characters because that’s the way of the world. The large events that move and shake nations certainly interest us and impact upon our lives, but for most of us, the bigger stories revolve around ourselves and our circle of friends and family. I didn’t see why it should be any different for the characters in a high fantasy secondary world.” — Charles de Lint

“Wolf Moon is an old favorite of mine. I remember at the time I started to work on it that I wanted to write a small story in a high fantasy setting. Worlds didn’t need to be saved. The characters weren’t required to go on arduous quests. But the events of the story would still have great import upon the characters because that’s the way of the world. The large events that move and shake nations certainly interest us and impact upon our lives, but for most of us, the bigger stories revolve around ourselves and our circle of friends and family. I didn’t see why it should be any different for the characters in a high fantasy secondary world.” — Charles de Lint

This is a small story, certainly. It follows a few events in the span of a few months. The people are ordinary — even the werewolf, the kimeyn, and the mage/harpist. But it is perhaps this very smallness that enables the story to tell an ancient and enormous truth in a way that is easy to hear.

Kern longs for friends, family and home, one of the deepest triads of human need. But Kern is also a werewolf, shut out of society by the incontestable fact that, in his wolf form, he can rip the throat out of a man or eat a small child. It does not matter that Kern has no desire to do such things. The mere idea that he can do them makes him dangerous in an alien, frightening way. So Kern runs from village to forest to village, never staying among people long enough to become suspect, always lonely.

Tuiloch is a harper, beloved wherever he goes. He also has no friends, family or home, but he denies any need for them. To stay anywhere long enough to make friends, to commit to a family, to build a home, would also mean staying long enough for the glamour to fade. To be loved and trusted would mean to be no longer adored, nor seen as larger than life. So Tuiloch feeds his emptiness another way: he hunts, killing and acquiring for himself animals who run wild and free. And if such an animal is also that rarer creature, a man who can shift between worlds and shapes, the hunt is all the sweeter and the acquisition all the more satisfying.

It is natural, inevitable, that Kern and Tuiloch are enemies. The hunted against the hunter. Warm heart against icy arrogance. Passionate yearning against indifference and monstrous greed. And their battlefield? An inn, of course. Inns straddle the border between the settled, human world of home/family/friends and the forest, the unknown. This inn, even more appropriately, is called The Tinker. Tinkers are folk who walk freely back and forth across the border, sharing in both worlds. For Kern, the people of The Tinker are potential allies — if he can trust them to trust him. For Tuiloch, they are pawns, traps to draw Kern to his death.

On this level, the level of conflict between good and evil, Wolf Moon is already a deep story, drawn in the starkest, simplest lines. But there is a deeper level here as well. The people of The Tinker are not only allies or pawns. They are also, each of them, people who desire, yearn, fear, and love. Ainsy runs the inn, proudly keeping them self-sufficient, secretly worrying about her wandering uncle, the old tinker himself. Wat loves Ainsy with his whole heart and gives her a brother’s devotion and fierce loyalty. Tolly and Fion are additional members of this tight family, helping Ainsy with the daily work and linking her to the larger circle of the village. When Kern joins this family, binding himself to them in love by the oldest ties of work, sweat, meals, and romantic bonds, he does not just defeat his enemy. He ends the battle and turns the battlefield into a field for the growing of the richest crop of all.

Small as a seed, this idea. Yes. But holding a truth that continually renews the world.

Charles de Lint, in this, the tenth of his books to be published, was already a master of the “small and ordinary” that lovers of his work have come to look for in everything he writes. He draws Kern with such detail that we come to identify with him and his concerns; his shapeshifting becomes simply another feature, rather than a strange, magical ability. Ainsy’s independence, coupled with her romantic leanings, make us smile. Fion is so strong, resourceful and clever that we find ourselves half-wishing that she might win the notice of the hero in the end. As well, the vivid descriptions of life at the inn — the work involved in raising and storing food, making meals, keeping warm, and the rare joys of an evening spent dancing — weave a strong web to link the events of the story as they move back and forth.

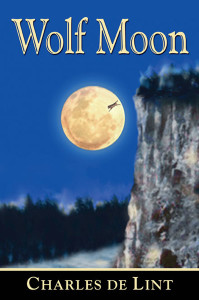

Subterranean Press (rather like those associations of farmers and gardeners who save seeds from plants that are in danger of dying out) has taken on the noble task of bringing good books back into print. Wolf Moon was originally published in 1988 as a paperback. This 2002 hardcover edition returns the book to circulation in a splendid incarnation. The binding is high quality, the pages falling open easily from the spine, the covers sturdy and warp-free. The paper is substantial yet smooth, the print sharp and legible, generously spaced on the page. The crowning touch is the dust jacket, featuring a lovely illustration by MaryAnn Harris, wife of the author. A full moon of luminous peachy yellow swims against a background sky of deep drowning blue. Arcing across the face of the moon is a wolf in full leaping extension. Perfectly small, balanced just exactly right.

(Subterranean Press, 2002)