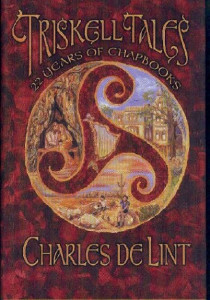

This, quite honestly, is a book that I’ve been looking forward to getting my hands on for quite some time. Years, in fact, long before the good people at Subterranean Press announced they would be putting forth this massive collection, complete with illustrations from the author’s talented wife, MaryAnn Harris. While I relish each new de Lint novel and the unexpected twists and turns his fey injections into modern life deliver, I’ve always felt his style was particularly well-suited for the short form. And that’s what’s delivered up in Triskell Tales.

This, quite honestly, is a book that I’ve been looking forward to getting my hands on for quite some time. Years, in fact, long before the good people at Subterranean Press announced they would be putting forth this massive collection, complete with illustrations from the author’s talented wife, MaryAnn Harris. While I relish each new de Lint novel and the unexpected twists and turns his fey injections into modern life deliver, I’ve always felt his style was particularly well-suited for the short form. And that’s what’s delivered up in Triskell Tales.

In 1977 a young Charles de Lint wrote a short fantasy story as a Christmas present for his wife, and had it printed and bound in an edition of one copy. That story “The Three That Came” introduced the enduring character of Cerin Songweaver in a mythic, high fantasy setting more reminiscent of Old World mythology than de Lint’s more famous fictitious city, Newford. The equally enduring character of Meran, the Oak King’s daughter, is also introduced for the first time in the Songweaver’s tale (although those familiar with de Lint’s later work may be shocked to discover that the lovely oak maid doesn’t even survive to the end of the story!). More importantly, however, this single story began de Lint’s annual Christmas chapbook tradition that continues to this day, a tradition responsible for the better part of this book’s contents.

Many readers will already be familiar with some of the tales contained herein through various reprints — indeed, from 1988’s The Drowned Man’s Reel on, nearly every story has appeared in the various de Lint collections of Dreams Underfoot, The Ivory and the Horn, and Moonlight and Vines. Not coincidentally, “The Drowned Man’s Reel” happens to be Meran and Cerin’s debut in Newford, that mysterious transplant that landed these fey figures in our modern society. Fortunately, their Old World roots are still showing. The ubiquitous Jilly Coppercorn makes her debut the following year in “The Stone Drum,” a tale that takes a closer look at the dark side of fey, and one that, had de Lint written it at the same time as “The Three That Came,” may very well have been Jilly’s last. “Crow Girls,” “Mr. Truepenny’s Book Emporium and Gallery,” “Coyote Stories” and all the other Newford stories contained here show de Lint at his best, a consummate, lyrical storyteller who weaves a rich, textured layer of feeling and mood around every character and subject — as often as not, tackling the darker, unpleasant aspects of our so-called civilized society.

That’s not why you should read this book.

If Newford’s all that interests you, then you can get a bigger fix through any of de Lint’s recent novels or the aforementioned collections. No, Triskell Tales is all about forgotten treasures. There was a time, quite a while back now, when no one had ever heard of urban fantasy, and de Lint’s writings were almost exclusively devoted to a rich, high fantasy landscape filled with enchanted musical instruments, wandering tinkers, shape-changing animal people and mysterious gods. Like most of the fantasy writers who came out of the late ’70s and early ’80s, there’s a distinctively Tolkienesque resonance in his work.

But unlike so many who viewed the Tolkien model as little more than a hero-quest template, even at this early stage in his career de Lint is obviously trying to craft the high fantasy setting into Something More. Using many of the same elements he would later apply to the streets of Newford — the unseen occupants of the world around us, animal people, music and the power of story, among others — de Lint establishes a unique and vivid world that’s as fully realized as Lower Crowsea or the magic-touched Tamson House in Ottawa. Not only do these wonderful stories give you a unique insight on things to come — once de Lint shifted his focus to contemporary matters while retaining the stylistic tools and themes developed here in this magical otherworld — but they also give you an elusive peek at what might have been. No doubt de Lint found his calling once he put bodachs on subways, and literature is better off for it. But there’s a freshness to his high fantasy work, an energy and eagerness to infuse myth and legend into what has become for the most part a stodgy, paint-by-numbers genre. Two of his early, obscure novels, Riddle of the Wren and Harp of the Grey Rose, utilized this world. But while these two books were (and remain) quite enjoyable reads, they were written by an author still learning his craft, still bound by the rules of convention and tradition in the post-Tolkien fantasy landscape. I can only wonder what magical hybrid would have resulted had de Lint used such a setting to wrestle with such weighty topics as in “Ghosts of Wind and Shadow,” “The Bone Woman” or “Heartfires.”

Svaha remains one of my all-time favorite de Lint novels simply because of the ambitious juxtaposition of elements and the breaking of established rules segregating mythology and science fiction, so I suppose there’s a case to be made that I just enjoy what’s different from the norm. De Lint’s early high fantasy stories certainly differ from the greater body of his work. There’s a folktale quality about many of these stories, and at times I found them reminiscent of a lighthearted, music-obsessed Fritz Leiber. And the selections of de Lint’s poetry presented here — quite an extensive sampling, spanning a variety of styles and approaches, including the handful of verses that sparked the romance between him and MaryAnn — easily explain where that lyrical style in his prose originates.

De Lint has fretted often about returning these older tales to public view, concerned that they will wilt in the light of day. He needn’t have worried. All that remains now is for de Lint’s remaining unpublished early stories and verse — “The Night of the Valkings,” “Stormraven,” “Woods and Waters Wild” and … well, trust me there’s a lot of them — to be collected into a volume all their own. If they’re even half as entertaining as Triskell Tales, then it would be a travesty to make fans wait even two years to see them, much less 22!

(Subterranean Press, 2000)