Sometimes it feels as though I am too easy on the things I review. Even the stuff I start off not liking, I listen to – or think about – long enough to see the good in it. And then I try to present a fair and balanced look in my review. Well, that stops right here!

Sometimes it feels as though I am too easy on the things I review. Even the stuff I start off not liking, I listen to – or think about – long enough to see the good in it. And then I try to present a fair and balanced look in my review. Well, that stops right here!

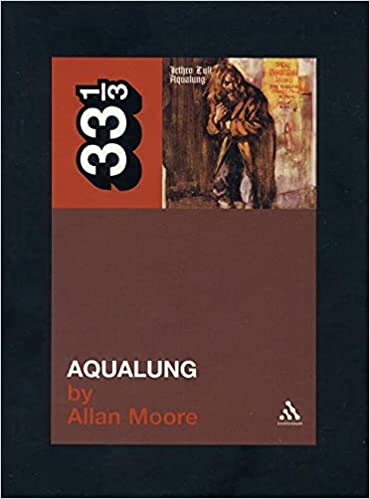

When I first heard that there was a book called Aqualung by Allan Moore, I thought they were talking about the great Alan Moore, comic book writer extraordinaire, author of Watchmen and V for Vendetta and The Killing Joke. I imagined him taking the classic Jethro Tull album and, together with one of his master collaborators, interpreting the songs in an illustrative and creative way that would once and for all explain Tull’s non-concept album!

Imagine that! Alan Moore’s imagination, coupled with, oh, I don’t know, Brian Bolland’s exquisite drawings, to show the following image in living colour:

Sitting on a park bench

eyeing little girls with bad intent.

Snot running down his nose

greasy fingers smearing shabby clothes.

Drying in the cold sun

Watching as the frilly panties run.

Oh yeah … count me in!

So imagine my disappointment when I found out that Allan Moore wasn’t a typo, and that the Aqualung on offer was part of the 33 1/3 series of books which seek to explain the intent and creation of a popular album as seen through the eyes of one or another of a set of music critics. Allan Moore? He’s a professor of Popular Music and Head of the Department of Music and Sound Recording at the University of Surrey. I knew I was in trouble.

Curiously, the book arrived a couple of days after I received a new recording of the album! That’s right, a new recording. Ian Anderson and his current mates (Martin Barre: electric guitar, Doane Perry: drums, Andrew Giddings: keyboards and Jonathan Noyce: bass) have released Aqualung Live as a special “collector’s edition in aid of various charities for the homeless.” More about that at another time and place, but let’s just say, the music was fresh in my mind.

And also, let me say that, as I listened to Aqualung Live that the first thing I noticed was not that “that first note (the ‘D’) . . . becomes a ‘D flat’. . . becom[ing] a foreign note, a transgression, a note that does not belong.” Nope. I didn’t notice that. I was too busy going, “Do-do-do-do-dooo-do” and doing that thing with my head that certain riffs just force you to do! Somehow I wasn’t thinking about the “switch 11” or the fact of the G minor, or any of that. I was busy digging the sound of Tull, man!

Now, to be fair, Professor Moore does say, “I’ve done the unforgivable – I’ve jotted down that opening riff, fixing it, draining it of its power so that it can be calmly pondered on the page.” So, if he knew that was unforgivable, why do it? He shows it there on the page, and it looks like nothing! Okay, you can read it, and whistle it, or hum it, but it’s not the same as hearing Jethro Tull play it! And why read about music when you can listen to it?

The book reminds me of that famous work of Wilfrid Mellers (if memory serves) that described the “Aeolian cadences” in Beatles’ songs. Give me a break! I suppose that there is a place for deconstructing music to this extreme, but popular music is not served by it. Popular music is like a house of cards and deconstructs only too quickly! And, well, listen to this observation, “there are a couple of very subtly, neatly bent guitar notes (on the top E string) at the ends of each of the first two phrases [of “Cheap Day Return”] (‘dance’ and ‘pants’, at 39″ and 45″ respectively) that, among contemporary artists, remind me of no one more than Simon and Garfunkel, with their tales of alienation within the big city (I have in mind songs like, ‘The Boxer’, ‘Mrs. Robinson’, ‘You Don’t Know Where Your Interest Lies’, where such guitar moments are prominent).” Did you ever think that Tull would remind anyone of Simon & Garfunkel? It’s the bent guitar notes!

Ian Anderson has said, (and is quoted by Moore) “there was no ‘concept’ involved, no narrative thread: ‘it doesn’t tell a story, doesn’t have any profound link between tracks.” Why then does Moore look for one? He also insists that on some songs Anderson sings as Anderson, sometimes as Jethro Tull, and also as Aqualung himself. Poor schizophrenic Ian Anderson. Now I can see him singing as himself and as the title character, all singers do that. But singing in the persona of the band is a new one! ” . . . [I]t sounds here not as if it is ‘Jethro Tull’ singing, but Ian Anderson himself.” That’s because . . . it is.

The book is short, only 110 pages, but it seems to go on forever. As I read, my wife said, “Stop grunting!” as I responded verbally with huffs and puffs on nearly every page. I hear that an upcoming volume from the 33 1/3 series presents The Band’s Music From Big Pink in a fictional context, a mystery in Woodstock, occurring as the album is being created. I’m looking forward to that one. As for Aqualung, I’m going to put Aqualung Live back in the CD player, and think about the graphic version that Alan Moore and Brian Bolland might have produced. Yeah, I can see it now! “Do-do-do-do-doo-do!”

(Continuum, 2004)

You can find out more about the 33-1/3 series at Bloomsbury’s website.