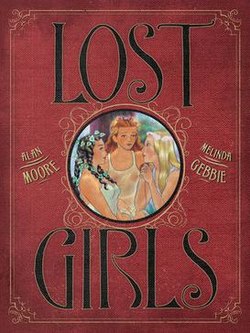

Lost Girls, the latest offering from Alan Moore, sheds light on three legendary literary women, exposing them in a unique fashion. Meet Alice, Dorothy and Wendy – yes, those young ladies, all grown up now – at a magical hotel in Austria, in the calm before the storm that will be World War I. They are, as the title suggests, lost. Lost in the sense that they have been running from their pasts, denying parts of themselves. What Moore has written is their stories, in their words, as they share them with one another in a most intimate fashion.

Lost Girls, the latest offering from Alan Moore, sheds light on three legendary literary women, exposing them in a unique fashion. Meet Alice, Dorothy and Wendy – yes, those young ladies, all grown up now – at a magical hotel in Austria, in the calm before the storm that will be World War I. They are, as the title suggests, lost. Lost in the sense that they have been running from their pasts, denying parts of themselves. What Moore has written is their stories, in their words, as they share them with one another in a most intimate fashion.

The twist is that the stories are not quite as we’ve come to know them. There is no Oz. No Neverland. No Wonderland. Those are all metaphors for sexual awakening, and the adventures each girl experienced in their respective tales were sexual in nature. So the stories that unfold in Lost Girls are intensely sexual. We learn that Alice had been sexually abused by one of her father’s co-workers (a stand-in for the White Rabbit), which caused her to avoid men and turned her to a life of opium abuse and lesbianism. Dorothy’s sexual awakening came in that famed twister, and has led her to be something of a randy farm girl. Turns out Peter Pan was a street ruffian, the Lost Boys orphans running with him. And Wendy’s experiences with him and “Captain Hook” were enough to scare her into marrying someone she knew she’d find no desire with.

And so Moore goes on to graft the various chapters and events of the three tales to the sexual escapades of the girls they were. Dorothy seduces the various men of the farm – a hulking, rude farmhand who turns all softie after sleeping with her; a lover with mechanical technique, and so on. Alice falls sway to the “Red Queen,” who keeps her doped on opium and forces her into degrading situations with the ladies of society. Wendy is desperate to sleep with Peter and is jealous of his sister Anabelle.

On paper the idea is very clever and seems fascinating. In execution, it sort of works, but not entirely. I thought at first that Alice’s story would play out best, but honestly, it’s Dorothy’s, until the big reveal of the “man behind the curtain,” which is somewhat creepy. At the risk of passing judgment on their behaviour, she seems to be the most well-adjusted, the happiest with her choices and in her skin. The other two stories are awkward, though, not quite so well a fit with the originals. Alice’s is so over the top as to be horrifyingly fascinating, but Wendy’s is downright painful (not hard to see why she’d want to repress her desire).

The women’s intimate knowledge of their pasts is learned as they gain intimate knowledge of one another’s bodies, awakening old desires and gaining new ones along the way. By the close of Lost Girls , they are lost girls no longer, having regained that which they’d lost: lost memories, lost emotions, lost sensations. They leave the hotel together, each with a new lease on life. Shortly thereafter, the hotel is destroyed, one of the first victims of WWI, its magic silenced forever.

The press materials accompanying the pre-release copy of Lost Girls have this to say: Why is this release so important? Because it does something that’s never been done before: reinvent pornography as something literary, thoughtful, exquisite and human. A singularly unique and layered story, Lost Girls is a commentary on the intimate wonder of human sexuality, the undeniable value of free speech, and the vulgarities of war.

My. That’s quite the mission statement for a three volume graphic novel. And to be quite honest, I’m not sure that Lost Girls lives up to any part of it, save the part about free speech. Moore illustrates that particular point in the third volume, when only the libertines remain behind at the hotel for one final orgy of pleasure, during which the proprietor reads from the quite pornographic book he’s stocked in every room, “The White Book.” He takes great care to differentiate between the incestuous acts of the fictitious characters in the book and the reprehensible act of pedophilia he’d just enacted upon a maid (ironic, since he himself is fictitious), claiming that it’s okay, since they are merely characters and not flesh and blood. A fine and valid distinction few are willing to make when it’s their children they’re trying to “protect” from “dangerous” comics.

And about all that sex. . . . Yes, there is a lot of it, and a lot of it relatively graphic. Sex to suit all tastes: men with women, women with women, men with men, orgies and considerably more. But to my mind, Lost Girls is neither particularly pornographic nor erotic. It’s simply filled with, well, page after page after page of sex, much of which is frankly boring after the first couple of jolts. A few years back, British film director Peter Greenaway filled the opening scenes of his movie Prospero’s Books with as many naked bodies of varying sizes and proportions as he could in an attempt to desensitize viewers to the bare human body — rather than to titillate. He got the desired effect (on me, at least). And here it’s much the same thing. After about the third or fourth page in a row of continuous sex in any particular scene, I would find myself ignoring the action on the page and simply reading the dialogue (although the sex permeated the characters’ speech frequently). Unless the art was particularly eye-catching, which would draw me back into the scenery. All of which is to say that all the sex didn’t bring me closer to Dorothy, Wendy and Alice; it distanced me from them, which I’m sure is quite the opposite reaction than was intended.

Much of the art is definitely gorgeous, particularly the sharp black and white inks rendered for “The White Book” itself. Alice’s story was always beautifully laid out, often in an elliptical manner (horizontal ovals on a white background), as if we’re only allowed a tantalizing peek into the story within a story. One chapter details the seven deadly sins along the right-hand side of the page. And ever so often we’re treated to a full-page colour spread – Dorothy first with the Cowardly Lion and later with the Tin Man, Wendy’s “Croc” devouring “Captain Hook” and Alice, in an opium haze, covered in tiny women. As you might surmise from the paragraph above, nudity abounds in the artwork, the human form (male and female, svelte and otherwise) in various states of dress, undress and arousal.

The press info also quotes the old adage about anything being worth reacting to is worth over-reacting to. And I suppose, sixteen years ago, when Moore and Gebbie began working on Lost Girls , perhaps the finished work might’ve been more shocking. I suppose to non-comic readers today – or those more used to traditional comics — it might still be shocking. But given I can walk into my local Borders, or go online and order from Amazon any number of manga titles that have plenty of sex in them – heterosexual, homosexual, lesbian – it’s neither new nor eye-popping to me. I read comics with sex in them on a weekly basis. Assuredly none as thought-provoking, since few authors of comics anywhere, in any language, are as talented as Moore, but comics containing varying levels of explicit sex are not uncommon, these days. And, frankly, since they’re not trying to be high art, they’re far more successful at being intimately human then Lost Girls.

Moore deserves kudos for delivering such a thought-provoking work, even if it doesn’t succeed on all levels. He will assuredly take flak for twisting beloved childhood stories in such a manner, and that’s a shame. For the record, I don’t mind; it’s an interesting take, even the execution falls flat. Do I wish there’d been less sex? Yeah, not because I prefer my comics tamer — far from it, actually — but because I really wanted more story (what about all those untold segments of the girls’ lives that could’ve been squeezed in if a daisy chain or two had been left out, hm?) and less action.

(Top Shelf, 2006)