Chris Woods penned this review.

Chris Woods penned this review.

In some ways it’s apposite that a book written about an artist as emotionally charged and mercurial as Sandy Denny should itself have had a difficult and rocky genesis. Some people, myself included, were expecting an biography of Sandy written by Pam Winters to be issued by Helter Skelter last year. It’s not my place as a reviewer to pass judgment on the disagreements which caused that project to flounder, and led to Clinton Heylin writing this book. Nevertheless, I include these comments to clarify the situation for those readers who do not know the background, why a biography did not appear last year, and why the author of this book, Clinton Heylin, is perhaps not the same author that they may have expected. It also helps explain the rather unusual comments in Clinton Heylin’s acknowledgments. Maybe one day that full story will unfold, but I shall keep my thoughts and comments on the book in hand.

Clinton Heylin is without doubt one of the best-qualified music writers to write a book about Sandy Denny. He wrote the earlier booklet Sad Refrains about Sandy Denny’s recordings in the ’70s, which was reissued a number of times before being republished together with Gypsy Love Songs, the chronicled recordings of Richard Thompson. The ‘buck ‘ was then passed to Patrick Humphries to write Meet on the Ledge, the story of Fairport Convention, and Strange Affair, the biography of Richard Thompson. It’s quite appropriate that Clinton Heylin should now return to the territory of his earlier booklets to recount the full story of Sandy Denny.

The book makes good use of interviews with people who knew Sandy, and draws extensively on Sandy’s notebooks and song lyrics, as well as including some of her drawings. It also quotes from numerous interviews which Sandy gave at the time.

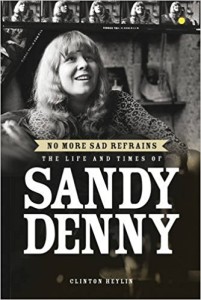

The proof copy I have does not reproduce them very well, but the book has a good selection of photos, many of which I don’t remember having seen before. Despite being a proof copy it’s refreshing clear of the type of obvious typesetting errors, like the missing capital Rs, which (failed to) appear in the recent UK editions of Strange Affair. The cover price of £19.99 I find rather expensive compared to similar biographies, but this is for a hardback edition, not the usual paperback. There is nothing to show when or if a soft-back edition might become available.

Perhaps the strangest feature of the book is that it starts at the end of the story, with a preface giving an account of Sandy’s tragic death. At first reading this struck me as an odd way to begin a biography, but on reflection it makes good sense for Heylin to have done this. There have been so many rumours, and there has been so much embroidery of the facts over the years, that I’m sure many of us have been unclear about what actually happened. The truth desperately needed to be told. Clinton has, with the help of testimony from friends of Sandy who were there at the time, set out the facts and circumstances of the situation as clearly as possible. To my mind this section alone justifies the writing of the book, as well as avoiding reader misconceptions throughout the rest of the book. To some extent the rest of the book could be summarised very quickly as being an account of what factors drove Sandy and resulted in that tragic situation, but what a tangled, complex, emotive and at times harrowing story this turns out to have been.

Chapters 1 to 4 of the book deal with Sandy’s early years as she grew up with her family, through the time she lived in London, her time spent working as a nurse and her experiences in the London music clubs. There are reminiscences from friends like Miranda Ward, Gina Glazer and Linda Thompson (then Peters) and from a number of the other artists she befriended. Although Sandy herself tried to avoid becoming categorised as a folk artist, she was part of the group of artists that included Al Stewart, John Renbourne, Bert Jansch, Danny Thompson, Dave Couzins, Jacqui McShea, Heather Wood and others who represented the new ‘resurgence’ of folk music in the London clubs of the ’60s. The book includes quotes from all of those people and more, plus reminiscences from music business people like Joe Boyd.

Although this section of the book is quite compact it manages to give a comprehensive insight into that part of Sandy’s life. She was already somewhat of a wild child of the ’60s. The life and soul of the party, and universally popular, yet already showing signs of the insecurity and lack of confidence that were later to become so significant. Despite her rising popularity and public acclaim, in an interview as late as 1967 she is quoted as saying, ‘I mean to acquire technical competence as well as quality and judgment.’

The time when she met up with and joined Fairport Convention is the next landmark. This period, spent with Fairport Convention, was previously the only documented part of Sandy’s life story, and although this book is from a different perspective and introduces some new material, much of chapters 5 and 6 are effectively an alternate take on the equivalent sections in the Humphries books on Fairport and Richard Thompson. If you have read those you have been (close to) here before.

The book gets back into untold territory again at chapter 7 as Sandy leaves Fairport and moves towards forming Fotheringay, and the book takes us through the Fotheringay years with her partner Trevor Lucas. At this time Joe Boyd could sense success if she would go solo and capitalise on her growing popularity, especially in the USA, and it’s at this stage of her life that the strains start to show, and opinions and memories start to become divisive. Sandy is under pressure to become a solo artist and stardom seems within her grasp but she has a drink problem. She is friendly with people that Linda Thompson describes as ‘seriously wild,’ like Keith Moon, Pete Townshend and Frank Zappa, and while Sandy can match them for drinking she is beset by self-doubt, and lack of confidence in her personal and artistic life. An additional complication is that she doesn’t like to travel, especially alone without Trevor and a band to back and support her. Meanwhile Trevor, who Sandy is relying on for emotional support, and who is seen by some people as the only firm anchor keeping her from further trouble with her excessive lifestyle, is described by others as a womaniser and opportunist riding on the back of Sandy’s talent and popularity. This is a polarisation of opinion which stays through the remainder of the story.

Part two of the biography, ‘The Solo Years’ starts at chapter 8 with the breakup of Fotheringay, financial problems, more pressure to make a solo break, and various misunderstandings, all of which further undermine Sandy’s confidence and drive her further into herself and into insecurity. Sandy seems by now to have been close to depression with severe mood swings, and even Sandy described her own songs as ‘melancholy.’ There were personality clashes with John Wood, who was producing her North Star album, dissension about the string backing put on the album, bad reviews for her first big solo concert — almost nothing in her professional life seemed to be going right for her. Basically, this period is a rather unhappy story however it’s told. We are left to wonder how some of the musical gems she recorded saw the light of day!

Eventually, we assume in an attempt to bring some order and security into her life, she and Trevor marry. Even then nothing was straightforward; some of her best friends and her father were so against the move they refused to attend the ceremony. Nevertheless, after the marriage, getting back together with Fairport, and with her brother in the team (almost, it appears, as a minder), it seems she did regain some control in her artistic and private life. The relationship with Fairport was far from smooth and the circumstances were far from ideal, but it provided some much-needed stability for a while.

By the time the book gets to Chapter 13 Sandy’s life was going increasingly downhill. It wasn’t all bad times, and she was still producing some marvellous music, but it seems that each low was just that bit lower than the one before. Sandy by now was desperate to become a mother, but by the time she became pregnant with Georgia we are told she was already experimenting with cocaine and still drinking to excess, with the result that Georgia was born 2 months prematurely by emergency Caesarian. With Georgia a young child, and now living in the country at Byfield, Sandy’s drinking and lifestyle excesses continued. Trevor Lucas’ perception that their daughter was not safe in her keeping finally prompted him to take the child and return to Australia. This precipitated the sad trail of events which ended with her life support machine being turned off on Friday, April 21, 1978.

I have been listening to music from the ‘Fairport family’ of musicians for many years. I saw Sandy onstage with Fairport Convention on a number of occasions and I used to avidly read the music press and keep up with interviews and news of the band and of associated artists. All reports have always indicated that Sandy had a fairly wild and excessive lifestyle, but nothing I have previously seen or read quite prepared me for the harrowing and upsetting scenes towards the end of this book.

The book doesn’t paint Sandy as the tragic heroine some may expect. She is portrayed as a unique and very special individual, and while the book makes abundant reference to how special she was, to her very considerable musical talents, and to the positive aspects of her personality, one is nevertheless forced to the conclusion that part of the cause of the ultimate tragedy was Sandy herself. Her self-doubt and her hedonistic and excessive lifestyle were a potent and self-destructive combination. Other characters are not portrayed through rose-coloured glasses either. The book records some harsh comments about Trevor Lucas and even Sandy’s parents, while many of her friends themselves admit to failing to see the signs and do something until it was too late.

My personal opinion, and others may disagree, is that Clinton Heylin has done an excellent job of remaining impartial and abstaining from overt personal judgment in this book. None of the comments and quotes are his, they are all culled from Sandy’s notebooks, song lyrics, her friends and associates, and interviews. But neither has Clinton Heylin pulled punches to appease the people portrayed or soften the truth. The impression I get from the book is that he has carefully set things in perspective and tried to give all sides of the picture in as objective a way as possible. After so many years, with Sandy and other key witnesses sadly no longer with us, this was probably a difficult journalistic task, and it is one he has carried out with an excellent blend of professionalism and sympathy and understanding for the people involved. We are all human, we all have flaws. While this book cannot help but bring us face to face with some of them, there is the simultaneous message that they are an essential part of the person, and without them the person would not be themselves.

‘Forgive the erring character who’s blemished none but their own soul’ – Sandy Denny, (undated)

I suspect a number of Sandy Denny fans won’t like this book. Some will be shocked and possibly won’t want to believe all of it. Quite a few will be upset by what they read. Indeed, it’s an upsetting and all too tragic story; anyone with feelings can’t help but be affected by reading it. Nevertheless, if you are at all interested in Sandy you must read this book — then go back and read it again!

(Helter Skelter Publishing, 2000)