When I was little, I thought of salamanders as the cute little amphibians I saw in the woods near ponds and under old logs. But I found out later that there are mythological salamanders, too, magical salamanders that live in fire and are as hard to catch as a dancing flame. Bullfinch’s Mythology mentions a story from the 16th century artist Benvenuto Cellini, who swore it was true:

When I was little, I thought of salamanders as the cute little amphibians I saw in the woods near ponds and under old logs. But I found out later that there are mythological salamanders, too, magical salamanders that live in fire and are as hard to catch as a dancing flame. Bullfinch’s Mythology mentions a story from the 16th century artist Benvenuto Cellini, who swore it was true:

When I was about five years of age, my father happening to be in a little room in which they had been washing, and where there was a good fire of oak burning, looked into the flames and saw a little animal resembling a lizard, which could live in the hottest part of that element. Instantly perceiving what it was he called for my sister and me, and after he had shown us the creature, he gave me a box on the ear. I fell a crying, while he, soothing me with caresses, spoke these words: “My dear child, I do not give you that blow for any fault you have committed, but that you may recollect that the little creature you see in the fire is a salamander; such a one as never was beheld before to my knowledge.” So saying he embraced me, and gave me some money.

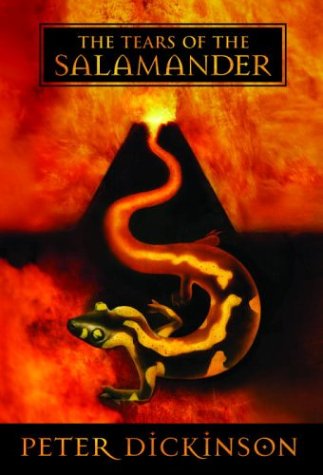

Peter Dickinson takes the salamander of myth and gives it a new spin in The Tears of the Salamander. In 18th century Italy, young Alfredo is a promising singer in the church choir, and sings with the true love of one born to it. Soon though, he reaches the age where he must make a decision: to become a castrati and continue with the choir for his whole life, or to take his chances and hope his singing voice after puberty is as good as it had been before. Then suddenly, tragedy strikes. Alfredo’s family is killed in a freak accident, leaving Alfredo grief-stricken and alone. He is soon introduced to his Uncle Giorgio, a man whom he has never known and whom his father hated. Alfredo is whisked away to Sicily, where his uncle is the Master of the Mountain, a powerful man with the fire and fury of the mountain at his control.

Alfredo quickly gets used to his new surroundings, including the housemaid Annetta and her son, Toni. But his uncle’s behavior makes Alfredo wonder if there is something more, something sinister, behind his uncle’s generosity. Soon, with the help of the salamanders of the mountain, Alfredo gets to the truth and finds out that his uncle is a fearsome sorcerer. Alfredo must protect himself and the friends he has come to know, as well as the villagers who depend on the Master for protection, but how?

This book is a quick read; the story takes off almost immediately and keeps things interesting from start to finish. Plus, Mr. Dickinson’s evocative style helps paint a picture of the people, places and things Alfredo sees, developing a world the reader can imagine almost effortlessly. This book doesn’t insult the intelligence of a pre-teen; though the writing structure of the book may be simple, Mr. Dickinson doesn’t talk down to his readers. He sometimes uses words that the average school age reader may not know, but hey, isn’t that what a dictionary is for? This is no vocabulary lesson, though. The author uses his words judiciously, because they’re what the sentence requires. He also has a way with describing the inner workings of a character’s mind, giving readers a good picture of what Alfredo is going through and how he comes to his decisions. The theme in this book, that you must trust in yourself, is also simple but presented effectively.

Alfredo himself is a well thought out character. Too many Young Adult writers develop their young heroes and heroines in much the same way artists before the 18th century painted children: as miniature versions of fully grown adults. Young Alfredo is just that: a young boy who longs for his parents, enjoys the time he spends playing with his friend, and walks the fine line between fear of and respect for his elders. Alfredo does move from innocent childhood to a more knowledgeable young adult as he wrestles with the decisions he must make, and his character develops at a believable pace. He doesn’t develop fully, but then the book only takes you through a particular moment in his life; at the epilogue, both Alfredo and the reader know that more changes are sure to come.

Alfredo’s uncle is less detailed. He’s more of a presence than a character, and his mysterious and fearsome nature feels a bit distant throughout most of the book. The author spends much more time describing Alfredo and Toni’s musical pursuits, which are beautifully written. Mr. Dickinson must have a love of music, because it shows in his descriptions of his characters’ musicality. As for the salamander of the title, it isn’t a creature of the friend/soul variety found in His Dark Materials, nor is it simply a creature with little thought, like Toto in The Wizard of Oz or Nana in Peter Pan. It’s somewhere in the middle, helping Alfredo as it is able, but never bonding in any permanent way. Perhaps that’s because it’s a creature of fire, and fire is at it’s purest nature a wild thing.

This doesn’t seem like a start to a series, but Mr. Dickinson leaves the possibility of more adventures open. That would be just fine, but the book stands well on its own. The School Library Journal has recommended this book for children in grades 6-9, and I agree. Although this book isn’t a difficult read, the topic of castrati and the brief hints at priests’ not-so-pure intentions towards their choirboys are probably not elementary school material. But a pre-teen interested in a page turner set in a world where salamanders sing and fire has a life of its own will burn through these pages. Hey, I couldn’t resist.

(Wendy Lamb Books, 2003)