Whenever two Babylon 5 fans meet, whether it’s at a used book store, a sci-fi speakeasy, or somewhere else that’s safe for our species, it doesn’t take long for conversation to turn to the required topics: “Who’s your favorite character?” “What’s your favorite season?” “What’s your favorite episode?” and so on. And whether your favorite character is Commander Sinclair (the real Commander) or G’Kar, whether your favorite season is the first or the third, it’s almost universally agreed that Season Five, Episode Eight, “Day of the Dead,” is one of the show’s top ten episodes.

Whenever two Babylon 5 fans meet, whether it’s at a used book store, a sci-fi speakeasy, or somewhere else that’s safe for our species, it doesn’t take long for conversation to turn to the required topics: “Who’s your favorite character?” “What’s your favorite season?” “What’s your favorite episode?” and so on. And whether your favorite character is Commander Sinclair (the real Commander) or G’Kar, whether your favorite season is the first or the third, it’s almost universally agreed that Season Five, Episode Eight, “Day of the Dead,” is one of the show’s top ten episodes.

What makes this amazing is that the script for this episode was written by a one-time freelancer, not a regular writer for the series. The writer even had to rely on a friend, John Sjogren, to be his “As a rabid Babylon 5 fan — is this cool?” tester. In spite of that, the episode fits seamlessly into the milieu, and even adds to its psychological and spiritual depth. As J. Michael Straczynski (the show’s executive producer) says in the introduction to Day of the Dead: An Annotated Babylon 5 Script, “This episode was a hit not only with the fans, but the cast and crew, who were charmed by him [the writer] while he was on set. Of all the freelance scripts that came into B5, this was the most effortless, the most fun, and the most insightful. When Captain Lochley recites her password, and we learn that the keyphrase is, ‘Zoe’s dead’, we learn more about her character in that two-second phrase than in the multiple hour-long episodes that preceded it.”

Perhaps it’s not so amazing, when you consider that the writer in question is Neil Gaiman. Effortless. Fun. Insightful. These are words that describe most everything Gaiman writes (for more GMR reviews of Gaiman’s work, see the alphabetical listing in our fiction index). When I first saw “Day of the Dead,” I didn’t know that Gaiman had had a hand in it. All I knew was that it had a wonderful plot; raised all sorts of interesting questions and didn’t provide pat answers; brimmed with humor that ranged from the deadpan “drumroll-rimshot” sort to the surprising-but-satisfying sort; and provided pathos that was well balanced between hopeless yearning and resignation. When I found out who had written the script, I said, “Ah, Gaiman. That explains it.”

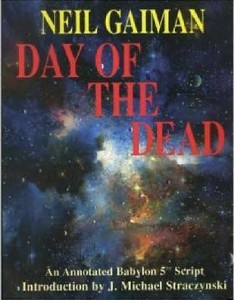

If you’re not familiar with the “Day of the Dead” episode, you need to read Asher Black’s review of it. Asher’s insightful overview and analysis say it all, and there’s no way I could hope to go him one better here. What I’m looking at is the script of the episode, which has been published in paperback form by Dreamhaven Books, with a portion of the proceeds going to the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

If you’ve never watched a film or play with the script open in your lap, you’ve missed a treat. I re-watched the episode, then read the script, then watched and read at the same time. It was fascinating to read the stage directions and see how the director and actors interpreted them. If you’re the sort of person who loves and follows a favorite television series and enjoys arguing interpretation with friends afterward, you’ll understand. This was like that, but with the added fillip of letting me glimpse the writer’s intention for each scene and emotional/verbal arc. In addition, I was able to see where parts of Gaiman’s script were cut during editing, and which were adapted. In some cases I disagreed with the director’s choice, in others I thought the changes were brilliant.

For example, Gaiman has Rebo and Zooty, a galactically-acclaimed comedian duo, make a visit to Babylon 5 during this episode. In a stroke of luck and directorial genius, the magician team of Penn and Teller were cast to play them. As you may or may not know, Teller — who plays Zooty — doesn’t talk onscreen. It’s part of the persona he’s developed over the years. The Bab 5 team got around this by giving Zooty an electronic voice box to carry around. When Zooty has a line, the voice box says it for him, using a classic ventriloquist’s voice. Not only is this an ingenious solution, it adds an extra dimension to Zooty’s character and gives Rebo and Zooty’s comedy more impact.

I’m not going to give away any more such details of the script here, because that would spoil your fun in discovering them for yourself. I’ll just reiterate that comparing the script to the filmed version has added to my enjoyment and understanding of the episode, and Gaiman’s annotations about why he chose certain plot elements (at one point, for example, we learn that one of the races subjugated by the Centauri was the Shoggren, which Gaiman threw in as a tribute to his “continuity man,” John Sjogren), or which filming changes pleased or frustrated him, are the sort of thing that make Bab 5 geeks like me crow with delight.

But even if you haven’t ascended to the upper eschelons of Babylon 5 geekdom, that rarified bunch of us who own recorded copies of the series, you’ll still enjoy reading this script. Reading a script is a bit different than reading a short story. The elements are similar, but you have to create a stage in your mind and play the story out on it. It can be challenging, but it’s also rewarding, especially when you have a script from a master like Gaiman to work with. He makes it… almost effortless.

(DreamHaven, 1998)