Beowulf changed into my life when I was seven. It was a dreary, endless afternoon, and I was rooting through my father’s shelf of dusty old college textbooks when my hand grasped a battered, musty paperback with a strangely evocative, savage image on its scuffed cover. I read the entire saga in one sitting with a fascination sometimes horrified, always enthralled. It went deep inside me and to this day still sends back echoes.

Beowulf changed into my life when I was seven. It was a dreary, endless afternoon, and I was rooting through my father’s shelf of dusty old college textbooks when my hand grasped a battered, musty paperback with a strangely evocative, savage image on its scuffed cover. I read the entire saga in one sitting with a fascination sometimes horrified, always enthralled. It went deep inside me and to this day still sends back echoes.

As with any first love, that translation of Beowulf is the only “right” one for me, although I have never found it again. I have collected several translations over the years, but none of them has made me murmur, “Ah, yes. This is Beowulf!” (although the translation in the Fifth Edition of the Norton Anthology of English Literature is quite lovely).

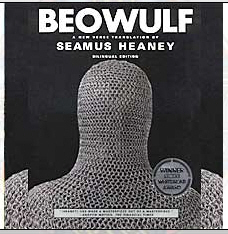

Naturally, when Nobel Prize winner Seamus Heaney published his translation in 2000, I had to take a look at it. My implacable lover’s eye was not satisfied. Now, considering that such illustrious publications as The New York Times Book Review, The Washington Post, and Kirkus Reviews — as well as several of my respected friends — have lavishly praised Heaney’s work, I expect a lightning bolt at any moment to sear me where I sit for daring to be unsatisfied. Ah, but who was it who said that bravado is everything?

I find Heaney’s written translation to be inconsistent to a point just this side of irritating. He switches back and forth from older, more formal language and grammatical constructions to modern ones. As I have said in another review, I have no objection to translations in modern idiom, not even translations of ancient and revered texts; but I prefer a translator to stick to one style consistently. Other reviewers and scholars obviously have no such sensibilities.

When I was offered an audio version of Heaney’s Beowulf, however, read aloud by the translator himself, I was unable to resist. Perhaps my lover’s ear would be less implacable than my eye…. And I can say quite happily that this has proved to be the case. Perhaps the key lies in the fact that, as stated in the liner notes, “Beowulf was not meant to be read on the page, but to be heard.” Heaney does a splendid job of reading his own work. His stately, sonorous voice, never rushing, brings to mind the chanting of ancient skalds. The alliteration that typifies this ancient style of poetry reaches out and catches the ear in relentless spirals. Stylistic inconsistencies, so glaring in print, are here overrun and swept aside by the force of the telling.

I recommend this recording, containing over two hours of Beowulf, for a dreary, endless afternoon. After hearing it, I will be surprised if you do not find your senses keener and your heart bolder.