Brendan Foreman penned this review.

Brendan Foreman penned this review.

During a recent festival in celebration of the works of Béla Bartók — one of this century’s most important musical composers — at Bard College, the Hungarian tradition revivalist band Muzsikás discovered that many people were quite familiar with Bartók’s classical compositions while being quite ignorant of the Hungarian folk musical traditions that inspired much of those compositions. In fact, Bartók was completely entranced by the traditional music of his people and became one of the first people to take full advantage of the advent of mobile recording technology in the beginning of the twentieth century and set out on many field-recording tours of Eastern Europe from the 1900s to the 1930s (this behaviour must have been genetic, since his son, Peter, also went on to become a famous field recorder and producer for the Folkways label during the Fifties). Much of the music that he gathered would become the raw material of many of Bartók’s later compositions.

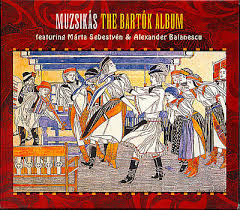

Thus, Muzsikás made this record, in order to demonstrate the relationship between Bartók and folk music and tell about his encounters with the people who played this music, recruiting several well-known musicians to help in the process.

There are a number of things that make this CD particularly innovative. First of all, it brings together two often-needlessly-at-odds worlds of modern-day music: the classical region (here represented by Alexander Balanescu, who might be more familiar to the readers as a major component of the Michael Nyman Band) and the international folk community (Muzsikás and Marte Sebestyan, who recently made a name for herself as the chief vocalist of the soundtrack to The English Patient). Although not a folk musician by any means, Bartók himself straddled the fence between these two worlds, being both one of this century’s most important musical composers and one of the first field recorders of European traditional music.

The second innovative aspect of this disc is its actual structure. More than just a celebration of Bartók’s achievements, this CD actually endeavors to study how his work as a field recorder and traditional music appreciator influenced and guided much of his compositions; and the make-up of this CD reflects this philosophy.

For three of Bartók’s compositions that were based on music that he had gathered from his field studies (Violin Duos Nos. 32, 28, and 44), Muzsikás have juxtaposed tracks of the original field recordings with their arrangements of related tunes (often found during their own field-recording expeditions) and a performance of the actual Bartók piece by Balanescu and Mihaly Sipos, one of the members of Muzsikás.

Although Bartók’s use of folk music is fairly common knowledge, it really is quite striking to hear how specific tunes and themes crept into his work. In fact, these selections — besides being some excellent music to listen to — are fascinating documents of the creative process, whereby we the artist (Bartók) taking pre-existing material and molding it into his own personal statement.

For example, for Violin Duo No. 28, “Sorrow,” Bartók used themes from a lamentful love song called “Pejparipam rezpatkoja (My horse’s shoe).” Muzsikás found two versions of this melody in Transylvania: a fast one known as a “Forgacskuti lads’ dance,” and a slower one (also, a lads’ dance) from the village of Bonchida. The jaunty, “rough and ready” feel of Muzsikás’ traditional stylings for these two tunes contrasts quite remarkably with the smooth precision of Balanescu’s and Sipos’ playing of the Bartók piece. But the differences don’t detract one method of playing from another at all. Rather the feeling is more symbiotic, like these are both two different aspects of the same musical style.

In between these three musical essays, are interpretations of various folk melodies that Bartók recorded during his field recordings. These tracks provide a beautiful cross-section of the many aspects of Hungarian traditional music, collected from several regions of Europe, ranging from the rippingly fast Transylvania czardas of the first track, to the slow, haunting “Pasztornotak hosszufurulyn (Shepherd’s flute song),” played by Z. Juhasz on the long flute. Emphasizing the “dance” nature of most of these melodies, “Pe loc (in place)” is a nifty tune played by P. Eri on flute and the feet stomping of two dancers, Z. Farkas and I. Toth.

On the many songs here, Marte Sebestyan gets to demonstrate her range. Particularly notable is the rather morbid “A temeto kapu (The churchyard gate),” whose lyrics describe a funeral from the perspective of the corpse being buried. Very noteworthy is the lamentful, a cappella “Porondos viz martjan (On the river bank),” in which Sebestyan recreates a richly ornamented styling of the Carpathian vocal traditions.

This is an amazing, bewitching CD that illustrates both the continuation of a musical tradition through the years and the transformation of one musical style into another (in this case, from the communal Hungarian folk traditions to the personal classical pieces of Bartók).

(Hannibal, 1999)