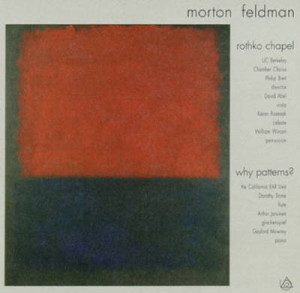

Morton Feldman, born in New York City in 1926, met John Cage in 1949; it is hard to say exactly how much influence Cage had on Feldman’s development as a composer, but one can surmise that the spare, non-dramatic quality of these two works, the Rothko Chapel of 1971 and Why Patterns? of 1978, owe something to Cage’s ideas of silence as sound and everyday sounds as music. This is not to say that one is to be subjected to the burr of airconditioners or random honkings of horns — on the contrary, both of these works quite definitely “music” as one might find in a concert hall. They share a sense of reverence, almost an otherworldly solitude, and each in its own way is quietly stunning.

Morton Feldman, born in New York City in 1926, met John Cage in 1949; it is hard to say exactly how much influence Cage had on Feldman’s development as a composer, but one can surmise that the spare, non-dramatic quality of these two works, the Rothko Chapel of 1971 and Why Patterns? of 1978, owe something to Cage’s ideas of silence as sound and everyday sounds as music. This is not to say that one is to be subjected to the burr of airconditioners or random honkings of horns — on the contrary, both of these works quite definitely “music” as one might find in a concert hall. They share a sense of reverence, almost an otherworldly solitude, and each in its own way is quietly stunning.

The spiritual as an impulse for art is an idea that is at once obvious and, in these times, often so tenuous as to be misssed completely, although even in our materialistic, expansionist, “growth-oriented” contemporary culture, our greatest efforts seem rooted in communion with something we can’t quite describe. When one hears of Rothko, for example, one will hear terms like “Abstract Expressionist,” “color-field,” “painterly,” and the like. Discussions of Morton Feldman will have words and phrases like “avant-garde,” “indeterminacy,” and “random notation” tossed casually about. And then, when one witnesses their work, the vocabulary becomes caught in a web of space, light, and indefinable presences — what Rothko called the “numinous.”

Rothko Chapel was first performed in 1972 at the Rothko Chapel in Houston, built in 1971 by the Menil Foundation to house the fourteen large paintings commissioned by John and Dominique de Menil. The Menils then asked Feldman to write a piece as a tribute to the painter, who had died in 1970. Feldman had been a friend of Rothko’s as well as the other Abstract Expressionist painters, and one can hear in the music Feldman’s deep understanding and appreciation of Rothko’s paintings. Feldman says, in the notes accompanying this recording, that “Rothko’s imagery goes right to the edge of his canvas, and I wanted the same effect in the music — that it should permeate the whole octagonal-shaped room and not be heard from a certain distance.” (I have never had the opportunity to visit the Chapel, but I have encountered many of Rothko’s paintings, including the Seagrams paintings installed as a group at the Tate Gallery in London. I can only surmise from seeing those that the Chapel must be a deeply moving experience.) The economy of Feldman’s music echoes the simplicity of Rothko’s imagery, and it is as hard to find antecedents for Feldman’s composition as it is for Rothko’s paintings. Both are definitively mid-century American avant-garde, from what is arguably the most fertile period in this country’s artistic history, and both are unique, each in his own way, but somehow there is a great deal more there than just paintings or a piece of music.

I don’t want to give the impression that Feldman’s score is an “illustration” of Rothko’s work — it most certainly is not. It might be more accurate to say that Feldman’s music and Rothko’s paintings open possibilties for each other. There is the same luminosity that I have seen in Rothko’s work at its best (a great Rothko does not hang on the wall — it floats in front of it), and in places the same transcendence — Rothko’s “the numinous.” This is music in which silence defines sound and sound very quietly and subtly fills space — it seems not to be “about” anything, but is somehow about everything, creating its own serene place for contemplation. This is not to say that there is no dramatic tension; indeed, there are passages of vivid intensity that contrast with passages of severely articulated coolness until the final section, which is dominated by a “quasi-Hebraic” viola solo that is quite traditionally melodic and quite beautiful.

Why Patterns?, at nearly thirty minutes, is an extended piece that shows a brilliant use of musical lines. One wants to call it a a trio for flute, glockenspiel and piano, but one cannot legitimately do that: the work consists of three separate series of patterns, one for each instrument, that are never precisely synchronized and only begin to coordinate toward the end of the work. If this sounds like a recipe for cacaphony, it is not; the piece reminds me in many ways of Toru Takemitsu’s November Steps, embodying a similar sense of imagery and a similar economy of means to create a quietly thoughtful work with passages of extraordinary delicacy. Structurally, it calls to mind the circular, seemingly formless gamelan of Indonesia — although in both cases, there is a definite, strong structure. This is visual music (and is perhaps something that many new age composers, particularly those who incorporate “nature sounds” into their works, would be well-advised to listen to and learn from); in part because of the instrumentation, and in part because of the way the various patterns are juxtaposed, there are long passages from which one receives the distinct impression of being in the country, on the verge of a woodland, perhaps, at the end of a rainstorm, as water drips from eaves and leaves and the first tentative birdsong begins to make itself heard. It is subtle, definite, and yet the idiom is very much that of post-Schoenberg, post World War II American music. It is an amazingly intricate work, absorbing and richly rewarding.

The performers acquit themselves well, displaying intelligence, a keen sensitivity to the needs of the music and great ease with the vocabulary of the contemporary repertoire. Both performances are excellent examples of true ensemble playing.

These are two remarkable works by one of America’s most noteworthy composers. They are ethereal, energetic, thoughtful, and yet possessed of a kind of earthy reality. Their intellectual underpinnings, which are formidable, become invisible, and one is simply left with an event that is out of the ordinary. Hearing them is an engaging and enlightening experience, and one I can heartily recommend.

[Deborah Dietrich, soprano; David Abel, viola; Karen Rosenak, celesta; William Winant, percussion; University of California Berkeley Chamber Chorus, Philip Brett, director; The California Ear Unit: Dorothy Stone, flute; Gaylord Mowrey, piano; Arthur Jarvinen, glockenspiel]

(New Albion Records, 1991)