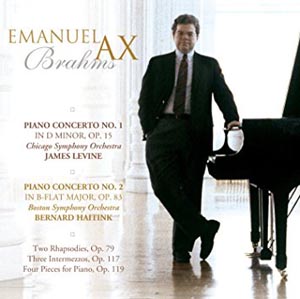

Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Minor, Op. 15 [Chicago Symphony Orchestra, James Levine, cond.];

Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major, Op. 83 [Boston Symphony Orchestra, Bernard Haitink, cond.];

Two Rhapsodies, Op. 79, Three Intermezzos, Op. 117, Four Pieces for Piano, Op. 119 [Emanuel Ax, piano]

If there is one characteristic of the works of Johannes Brahms that can be called definitive, it is scale. I don’t mean length or number of performers — in those areas he was far outstripped by Berlioz, Wagner, Mahler and Busoni, to name a few. I’m really referring to conceptual size as reflected in the architecture of each work. I’ve remarked before that even in his works for solo piano and his chamber music, one has the sense of a full symphony orchestra hovering in the background, just waiting to get into the act. In turn, the symphonic works, including the two piano concertos, give the impression of being much larger than they are.

If there is one characteristic of the works of Johannes Brahms that can be called definitive, it is scale. I don’t mean length or number of performers — in those areas he was far outstripped by Berlioz, Wagner, Mahler and Busoni, to name a few. I’m really referring to conceptual size as reflected in the architecture of each work. I’ve remarked before that even in his works for solo piano and his chamber music, one has the sense of a full symphony orchestra hovering in the background, just waiting to get into the act. In turn, the symphonic works, including the two piano concertos, give the impression of being much larger than they are.

It may seem odd that Brahms, whose works for many people define nineteenth-century German romanticism, was enough of an innovator that his first piano concerto, the D Minor, was greeted with first, polite incomprehension, and second, outrage. It’s too much of a cliché to be ironic that we recognize the D Minor as one of the greatest works in the canon (after all, there is the archetype of the misunderstood artist to uphold). From our vantage, it’s hard to realize just how revolutionary this work was at its premiere in 1859. Prior to Brahms, a concerto was simply that: a concert piece featuring a solo instrument with an accompanying orchestra, the orchestra usually being fairly unassuming and well-behaved. What Brahms wrote (and this makes great sense if one looks at the history of the work, which actually began as a symphony) was a symphony with a piano in it.

The work itself has always been one of my favorites (and, it turns out, one of Emanuel Ax’s as well). The powerful, brooding opening still brings a gasp and a depth of engagement that lasts through the lyrical second movement and the headlong rush of the third (although there is breathing space enough there for a wry and deliciously Beethovenesque little fugue that drops in out of the blue — never let it be said that Brahms lacked humor). In spite of what you may have heard of Brahms’ “Olympian” detachment, and although this work has a Brahmsian size to it, it is a work that demands involvement: the writing leaves little room for distance. It contains within that long architectural line that is so characteristic of the composer a series of detailed, intimate passages that throw the thundering climaxes into stark relief.

The D Minor is a young work, among the earliest of Brahms’ compositions to be publicly performed (remember that it was begun in 1854). It is full of fire and passion as well as that particularly gentle lyricism with its quality of sweetness that always surprises me in Brahms, although I should be used to it by now. In that regard, although I have great admiration for James Levine and am coming to appreciate Emanuel Ax as a talented interpreter, I felt that there were sections where they were milking the sweetness and losing the fire. The second movement just misses saccharinity in places, not something that one normally thinks of in relation to Brahms, and there are several passages in the third movement that take on a stateliness that came close to destroying the momentum of what is, overall, a furiously driving movement with a few pauses for breath. I will hand it to Ax, however: in the very tricky transition from an orchestral climax to a long, flowing arpeggio for piano solo just before the finale, he managed it with nary a stumble, which I can’t recall hearing anyone else do, ever. Kudos for that.

It just goes to show how audiences will eventually adapt to anything, no matter how revolutionary. Of course, by the time his Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major was premiered in 1881, Brahms was a household word. The B-flat Major is like the D Minor only more so: a truly integrated “modern” concerto in which the piano and the orchestra each maintain their identities but nevertheless combine into an amazing synthesis. This is the mature Brahms, in full command: the transitions are seamless, the rough edges smoothed, the scale grander, the intimacy closer, and that incredible architecture is more solid, more real, and if anything, clearer. All the passion and energy of the D Minor are still in evidence, but more confident, more polished, and the more potent for it.

Bernard Haitink is one of my favorites from his many recordings with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. This version of the B-flat Major with Ax and the Boston Symphony is a treat. I have to admit, Brahms’ “other” piano concerto was not, until now, one of my favorites, but this recording made me rethink my position on that, for which I am eternally grateful: this is without doubt one of the greatest works of Western music.

Ax’s performances of the Rhapsodies, the Intermezzos and the Four Pieces for Piano reveal both his intelligence and his sympathy for the material. These are, by and large, among the composer’s more intimate works, but there is still that hint of something much greater, which Ax taps into while maintaining the closeness (which, after all, is relative, particularly when dealing with Brahms).

As for the question of whether this is the recording to have, the answer becomes subjective. In spite of my reservations about the treatment of the D Minor, I am very happy to have the set in my collection, and I will say, yes, this certainly deserves a place in our basic library of classical music.

(Sony BMG Music Entertainment, 2007)