Eric Whitacre is one of those contemporary composers whose background is as patchy as it is eclectic. He was thrown out of his high-school marching band, in which he played the trumpet, for being a troublemaker. As a teenager he played synthesizers in a technopop band, with the aim of being a rock star — or at least the dream. He then joined a chorus, reportedly by accident, at the University of Nevada, which he was attending as a Music Education major. He participated in a performance of the Mozart Requiem and, it seems, the die was cast. His first work for chorus, “Go, lovely Rose,” was published when he was twenty-one, and since then his work has centered largely around choral music, although his first major success, Ghost Train, was written for symphonic wind band.

Eric Whitacre is one of those contemporary composers whose background is as patchy as it is eclectic. He was thrown out of his high-school marching band, in which he played the trumpet, for being a troublemaker. As a teenager he played synthesizers in a technopop band, with the aim of being a rock star — or at least the dream. He then joined a chorus, reportedly by accident, at the University of Nevada, which he was attending as a Music Education major. He participated in a performance of the Mozart Requiem and, it seems, the die was cast. His first work for chorus, “Go, lovely Rose,” was published when he was twenty-one, and since then his work has centered largely around choral music, although his first major success, Ghost Train, was written for symphonic wind band.

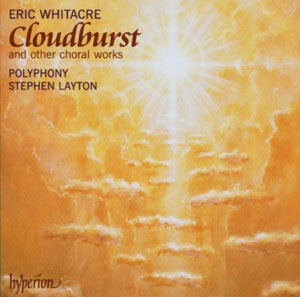

The selections presented in Cloudburst and Other Choral Works reveal the diverse influences that have provided a foundation for Whitacre’s writing, from the progressive rock of his pre-college days through his classical training at Juillard. Meurig Bowen, in the essay accompanying the disc, notes that Whitacre’s eclectic influences are something he shares with many of the younger generation of American composers. I might point out that it is also similar to the background of the performers who are making these works known, as well as their audience.

These works are, in all essential respects, small-scale secular works. There are traces of the kind of jagged edges and massive sonorities that are more or less expected in contemporary choral music, but there are also subtlety and ingenuity along with a sometimes amazing economy of means.

The title track, with a text by Octavio Paz, is one of the most immediately striking, combining passages of extreme tension with eruptions of powerful sound in a fluid architecture that culminates in a very satisfying finale. The other piece that struck me most was “When David Heard,” which does, in places, come close to that wall of “white light” that so much typifies Arvo Pärt’s work, most notably in a section that leads almost immediately into a lilting, almost broken-gaited passage that is more than a little magnetic. The finish of this piece is about as beautiful as choral music can be, which is really, really beautiful.

Polyphony, under the able direction of Stephen Layton, renders these songs with great depth and seamless artistry. Like many contemporary vocal groups, Polyphony is equally at home in the baroque and avant-garde repertoires, and this disc is a good example of their work.

In the final analysis, the selections included in this disc can’t really be written about very effectively. Whitacre’s music demands listening, which is about the highest praise I can give. He has absorbed his diverse influences and synthesized them into a flexible vocabulary that seems able to meet any challenge. Although he professes not to recognize the “popular culture/high culture” distinction that is seemingly a fundamental divide in American art, he is doing what a number of practitioners in other mediums have done from the time out of mind: it’s the interchange between the vernacular and high cultures that has enriched both for centuries, if not longer. Whitacre fuses the means and methods of high art with those of the popular culture and brings that back into a new synthesis in the realm of high art. In this case, his seamless melding of the tonalities, rhythms, and formal structures of both popular and art music gives us something new that sounds, at first, very familiar, although this is by no means a complete or even adequate summation: Whitacre’s music is too subtle and too sophisticated for that kind of reductionism.

Polyphony is joined for “Cloudburst” by Stephen Betteridge, piano; Robert Millett, percussion; Fran Fowler and Alice Heath, handbells; Suzanna Rennie, thunder sheet; Eva Redman, wind chimes; and Cecily Scott, suspended cymbal.

(Hyperion Records, 2006)