Craig Clarke penned this review.

Craig Clarke penned this review.

Blind Faith was arguably rock’s first “supergroup!” The conglomeration sprang from the breakups of Eric Clapton’s previous band, Cream, and one of the many breakups of Steve Winwood’s Traffic. Clapton and Winwood had planned to work together for some time and quickly took advantage of the situation. After Cream’s drummer Ginger Baker began popping up for the early jam sessions, they let him stay on — despite the ego-clashing that had partially led to that band’s split, and the idea that Winwood might simply be seen as a replacement for Cream’s third member, bassist and vocalist Jack Bruce. Baker was simply too good to turn away. It was at this point — as a trio — that they began to expect a band was in formation. For a while, Winwood took on bass duties along with his organ and vocal responsibilities (as shown on the jams on disc two), but this proved taxing and Rick Grech (of Family) was brought in later as a bass player. Recording began in February of 1969 with a cover of Buddy Holly’s “Well All Right.”

The new 2000 Deluxe Edition reissue of Blind Faith’s eponymous (and only) recording adds nine more tracks to the original six-song album, spreading over two discs with the second consisting solely of four extended jams with minor descriptive titles like “Very Long & Good Jam” and “Slow Jam #2.” The original album sounds better than ever, with “Can’t Find My Way Home” so crystal clear you could break it with a misplaced drumstick. (An electric version occurring later on the disc is fine but adds nothing to the mystique.) Despite the presence of Clapton’s guitar and Baker’s drums, the stars of Blind Faith are Steve Winwood’s soulful voice and keyboards. Generally involved in his own set of ego-clashing with Traffic’s on-and-off member Dave Mason, Winwood is freed up here and allowed to stretch his abilities as never before.

“Had to Cry Today” begins the album with the powerful two-thirds-of-Cream combo, but it’s Winwood who makes it soar. Clapton exhibits a lot of restraint on the album, occasionally unleasing a fiery solo, but mostly content to provide solid melodic support. His fretwork on “Can’t Find My Way Home” is so light and airy as to be — for the time — almost entirely out of character. Even Baker’s presence is hardly felt on this track, existing primarily in punctuating cymbal crashes until he sneaks in (not a sentiment typically used with Baker) about halfway through and lightly thumps out an ending. The whole band is in top form here; an absolute rockclassic.

The abovementioned “Well All Right” shows that the band was a unit from the beginning, with all four members working together seamlessly from the first measure. It is that rare track on which every member’s presence is felt, with Grech’s frenetic (for a bass player) fretwork being a standout. But even that is overshadowed by Winwood’s closing piano solo. First Clapton was God, then Clapton found God in his one compositional offering, “Presence of the Lord”, a gospel-tinged inspirational number perfectly suited to Winwood’s powerful Ray Charlesian pipes — at least until Clapton steps in and takes over with a solo that is somewhat out of place but no less startling in its ferocity. “Sea of Joy” is by far the weakest track on the album, seemingly unable to find its footing and trying everything in the process (Grech even throws in some violin for good measure); Winwood can’t seem to decide what notes to sing and it fades out most unassuredly, unlike “Do What You Like,” which seems to know its way from the beginning.

Like many a Baker composition, “Do What You Like” is mainly an excuse for an extended drum solo, but Blind Faith makes it into something extra before and after. It’s second only to “Can’t Find My Way Home.” Ringing guitar, accompanying wheezing organ, the underlying mantra of “dowhat…youlike…dowhatyoulike,” and — heavens! — a bass solo. And everything fades slowly away, almost imperceptibly until, nine minutes in comes that first pound that lets the listener know that the main show has begun. Baker has a repertoire of licks that he puts to great use here, far outstripping the “sneakers in a dryer” effect of Cream’s “Toad” (the Wheels of Fire version). It probably helps that it only takes up four minutes and doesn’t overstay its welcome. The track (and the original Blind Faith) ends in a disarray of wrong notes (Winwood calls out “D-flat!”), random phrases (“ding dong billy bong”), a selection of impressions (among them Peter Lorre, Edward G. Robinson, and a chicken), and the sound of the tape spooling at the wrong speed: the unsatisfying sign that this classic rock album has come to an end.

The five tracks that follow on disc one include two versions of the Sam Myers-penned “Sleeping in the Ground,” the first of which originally appeared on Clapton’s Crossroads box set and the second a “slow blues version” with a much deeper arrangement. Also on hand is the electric version of “Can’t Find My Way Home,” fascinating for its historical import only, as it is inferior in every way to the album rendition. Winwood’s “True Winds” is an instrumental that is interesting only as an artifact. The “Acoustic Jam” is a jazzy piano number with occasional vocal punctuation that doesn’t develop much over its near-16-minute running time. Surprisingly, this lends it a hypnotic (one may even say soporific) effect. Whether this is good is left up to the listener. In any case, it is the only jam on this deluxe edition that features all four band members.

This fact, of course, makes disc two a showcase for the three “famous” members, the ones that made people wonder if Blind Faith was simply Cream II: Clapton, Baker, and Winwood. These four jams don’t add a whole lot to the Blind Faith canon, but they are pleasant enough. Track 1, “Very Long & Good Jam,” is actually a bit tedious and repetitive. That’s the nature of jams, of course: not to call too much attention to the skeleton while leaving room for improvisation, but from these guys I expect a little more. Track 2, “Slow Jam #1” (not too creative with the titles, either, are we?), is more blues-influenced. Clapton keeps the guitar down low and grinding and the music is peppered with the screams of Ginger Baker. “Change of Address Jam” is the most interesting due to Winwood improvisatory organ skills, but even it is hindered by a strange, decrescendo finish. “Slow Jam #2” starts with some fine sticking from Baker, quickly loses its way, but has the most interesting ending: the tape just stops.

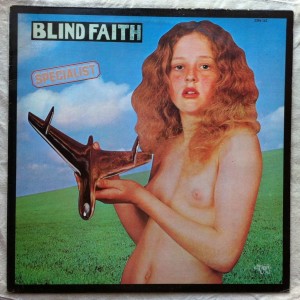

For collectors and rabid fans of the artists, this deluxe edition is probably worth the extra cash, given the expanded and informative liner notes and the extra 90 minutes of music. It includes the cover art from both releases of the album, though the barely-pubescent girl with an airplane is featured and, unlike the previous issue, unable to be hidden from sight. (Sometimes I just don’t want to look at a topless twelve-year-old.) But, in the end, the music that is most important to the legacy of Blind Faith was released in 1969 on that original album. Those six songs, despite their flaws, will long outlast the curiosities tacked on to this edition in order to double the price tag.

(Polygram, 2000)