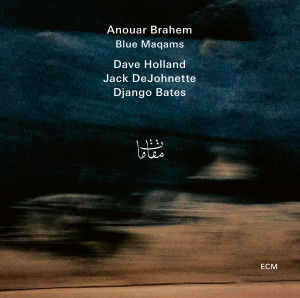

There’s a moment a couple of minutes in to the title track of Anouar Brahem’s exquisite new album Blue Maqams that is the kind of moment I long for, like a thirsty person in the desert longs for a cool drink. Brahem on his oud, accompanied only by drummer Jack DeJohnette, takes some time to set up the piece’s rhythm and mode (its maqam, as it were) and hint at the structure of its melody. Then abruptly the bass of Dave Holland and piano of Django Bates join in with a fully shaped tune that is as blue as can be. The melody itself exists in the interplay of oud and piano, and what a sweetly melancholy melody it is, its changes tugging the heart downward in what feels to me like a hopeful nostalgia.

There’s a moment a couple of minutes in to the title track of Anouar Brahem’s exquisite new album Blue Maqams that is the kind of moment I long for, like a thirsty person in the desert longs for a cool drink. Brahem on his oud, accompanied only by drummer Jack DeJohnette, takes some time to set up the piece’s rhythm and mode (its maqam, as it were) and hint at the structure of its melody. Then abruptly the bass of Dave Holland and piano of Django Bates join in with a fully shaped tune that is as blue as can be. The melody itself exists in the interplay of oud and piano, and what a sweetly melancholy melody it is, its changes tugging the heart downward in what feels to me like a hopeful nostalgia.

It’s a sublime moment in an album that’s full of such moments. Of course, what would you expect from a quartet of such masters?

The Tunisian Brahem, who turns 60 this month, has been playing with jazz improvisers since the 1980s. A master of the oud, he started playing Arabian music as a youth, and has also followed a fascination with other forms including Balkan. He has collaborated with bassist Holland before, but this is his first work with DeJohnette or Bates. In various collaborations with jazz and world music players over the years, he has explored the spaces where the varying traditions can meet, as well as contrast and diverge.

The pairing of piano and oud is a revelation. The oud has a range somewhat like a cello’s, similarly warm but a little less deep due to the size and shape of its body. A piano in capable hands like Django Bates’ provides vast options for shading and tonal combinations between the two. It’s evident everywhere here, in places both composed (halfway through “La Passante,” when the advent of the oud opens up the previously hermetic solo piano piece) and improvised or apparently improvised, such as the intricate introductory section of the lengthy “Persepolis’s Mirage.” That one opens out into a work that is unmistakably jazz, especially in the playing of Holland and DeJohnette, but also in the changes, such as the minor dip about two-and-a-half minutes in.

Other Middle Eastern players have recognized an affinity for Brazilian music, as does Brahem. All of the pieces on Blue Maqams were composed between 2011 and 2017 except for two bossa-like works, “Bom Dia Rio” and “Bahia,” both of which were composed in 1990 and revived for this project.

The album is bookmarked by works at the opposite ends of Brahem’s spectrum. The first track “Opening Day” is more clearly on the Middle Eastern end. After a free-form oud intro Brahem is joined by Holland, then DeJohnette’s signature cymbal touches with subtle tom and kick. Bass and oud play an intricate dance of a melody that can only be called contrapuntal; then Bates adds a third part, his piano making that dance even more intricate until all four members of this finely tuned quartet are weaving a lovely tapestry where rhythm and melody are nearly indistinguishable.

The closer, “Unexpected Outcome,” seems to me a little bit more overtly blue and jazzy, from the opening bars where Brahem and Holland again set up the piece with a delicate introduction, this time in unison instead of counterpoint. The ensemble covers a lot of ground in this 11-minute piece, from a lengthy solo oud section; to one with Brahem singing wordlessly in a tune that could be either Arabic or Brazilian; to a lengthy oud improv over a quick march pace set by a walking bass line and near-martial toms; to a long piano improv that passes through several moods to a placidly chaotic finale.

But nothing quite matches the magic of the title track, for me. With a lengthy oud improvisation sandwiched between two iterations of that lovely melancholy melody, it’s a piece that I doubt I’ll ever get tired of.

Here’s a taste of the album from ECM’s Facebook feed.