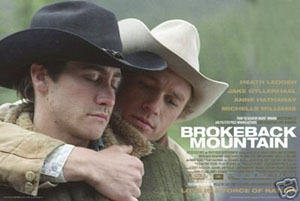

I remember seeing Brokeback Mountain at its first showing in Chicago. I sat through it, along with a fairly substantial audience, which surprised me a little — it was an 11 a.m. showing on a Friday morning, but the house was nearly full. No one was talking much as we filed out. I walked around for about an hour in the snow and the wind. I couldn’t think of anything else to do.

I remember seeing Brokeback Mountain at its first showing in Chicago. I sat through it, along with a fairly substantial audience, which surprised me a little — it was an 11 a.m. showing on a Friday morning, but the house was nearly full. No one was talking much as we filed out. I walked around for about an hour in the snow and the wind. I couldn’t think of anything else to do.

Based on Annie Proulx’ 1997 short story that first appeared in The New Yorker, the script is a fairly faithful adaptation by Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana. To my mind, it is the best kind of adaptation: it keeps the rhythms of the story, the spareness, the presence of the land, but takes on its own identity as the core of a film.

The plot is simple (and fair warning: I will be discussing various scenes from the movie throughout this commentary): two young ranch hands, Ennis del Mar and Jack Twist, meet in 1963 on a summer job herding sheep on Brokeback Mountain in Wyoming. They fall in love. After their first tumultuous sexual encounter, both are at pains to make it clear that they are not “queer,” but it soon becomes apparent that there is something profoundly important happening between them, whether or not they can put a name to it. The film follows the course of their affair (which seems too small a word) over the next twenty years, a thing of “fishing trips” two or three times a year as both follow their different lives: Jack marries a rodeo queen and becomes a successful farm equipment salesman in Texas, while Ennis stays in Wyoming, marries, and drifts from job to job, always wanting the openness of ranch life. He and his wife Alma eventually divorce — she has been aware of his feelings for Jack since seeing their first reunion, and he has grown more and more remote while she has grown more bitter and angry. Ennis eventually receives word of Jack’s death in an “accident” and makes a visit to Jack’s parents to pay his condolences. It’s quite clear that Jack’s death was no accident, at least in Ennis’ mind: Ennis is haunted by the childhood memory of a murdered rancher, who lived and worked with another man, beaten to death with tire irons.

In formal terms, the movie is not adventurous but is exceptional: pushing the envelope is not a prerequisite for excellence. The adaptation, as I noted, is faithful to the story but does become its own thing: there are lines from the story that appear in the film, and if you’ve read the story, you find yourself waiting for certain scenes — most of them are there, but the story is fuller. It is a romance, as was Proulx’ original, but the film is cast in much more romantic terms: Proulx’ story is terse, hard-edged, while the film is less severe in its rendering, but no less uncompromising.

What is most important, I think, is that the script gives the cast the means to get to some hard, dangerous places, and the cast delivers. Heath Ledger, as Ennis, is so inarticulate as to veer toward caricature, but he never quite goes over the edge, although his taciturnity becomes a small running joke throughout the story. He delivers a performance that is literally stunning. Jake Gyllenhaal’s Jack Twist is almost perfect — so close, in fact, I am still trying to find a flaw. Jack is more self-aware than Ennis, more accepting of his needs, and we can see his attraction to his silent friend within a very few minutes — nothing obvious, but it’s there if you look. He is vulnerable and seductive. The supporting cast is achingly real. An illustration: in a scene at the end of the movie, Ennis’ older daughter, Alma, Jr., comes to tell him that she is to be married and to ask him to attend her wedding. It’s a small scene, almost a throw-away. I found myself with goosebumps: Kate Mara as Alma, Jr., was flawless. In this cast, she was not unusual.

OK, so it’s a good movie. What does it mean?

The film is being touted in most quarters as the “gay cowboy movie,” and there are even commentaries that discuss the subversion of an American hero. (I should note that Proulx was quite definite that Ennis and Jack are not cowboys, but ranch hands, a distinction that is probably lost on most people and one that, ultimately I don’t think makes a difference: the archetype is there.) That’s one side of the cowboy archetype: strong, laconic, unremittingly heterosexual, an icon of so-called “American values,” the real conqueror of the Wild West. There is another American archetype to be read from the same image: also strong and laconic, but equally, earthy, immediate, and intensely sexual, with nothing hetero about him. The “subversion” in both Proulx’ story and Lee’s film is that they fuse these two readings and dig beneath them to reveal the humanity of the particulars, especially in the character of Ennis. It’s the reality of the cowboy in a context that carries the romance, but also places him in the middle of a fairly gritty reality composed of grandeur on one side and poverty on the other. This archetype is essential to understanding Ennis: he truly is a cowboy in that image, but by the same token, he has no way to define what or who he is outside of it. One of the great ironies of the film is that Ennis partakes of a mythic dimension — he has, at least in part, built himself into it — but he’s also trapped in it. That is at the bottom of his tragedy: he’s not a myth, he’s a man.

As much as gay men want to claim some ownership in this work, it really leaves that limitation far behind it. Although “gay” has become common shorthand for men who have sex with men, that in itself is a trap: it’s a film about men, yes, but it has a much larger dimension than “gay men,” no contact with any sort of gay identity or culture, and manages to reach past definitions into a more fundamental humanity. The film quite deliberately does not play the gay card, and forces us to reevaluate our perspective from the ground up, without the identity politics. There is nothing exceptional about Jack or Ennis: they are who they are, specific, individual, each with his own history and needs, ultimately just two people who meet and fall in love, and because of who they are, they can’t acknowledge it, not to the world, and in Ennis’ case, at least, not to themselves.

Add in another American icon: the Western landscape. Strangely enough, I’ve seen a couple of remarks disparaging Lee’s use of panoramic shots of the Wyoming mountains, which strikes me as a cavil, either deliberate or blind. I hadn’t realized that beautiful scenery was necessarily a bad thing in a film, and place has a distinct relevance to character. It’s something that is very hard to capture, a subtle influence that seeps into your bones: your place becomes a necessary part of your identity. Proulx caught it in the diction of her story (in itself revealing of how place shapes people), and Lee captures it in the contrasts between the immensity of the mountain and the intimacy of the scenes between Jack and Ennis: they make a private place where they can be tender and alone together, where they can have their romance, even though, or perhaps because, outside that place is a world that is sometimes too big to comprehend, a world that is incapable of providing the gentleness they need. Rodrigo Prieto’s cinematography is not particularly lush: it captures the scale and the hardness of the mountains as well as the banal emptiness of Ennis’ life in town. Any beauty in these views belongs to that land, and both Ledger and Gyllenhaal have brought that bigness, that hard and unforgiving beauty, into the characters of Ennis and Jack. (I find a distinct parallel with the photography of Robert Adams and his treatment of humanity against the landscape of the American West.) Both bring an intense physicality, a hunger to their roles, men whose only means of expression seems to be sex or a fist-fight, all of a piece with the extremes of the landscape.

This is not a story of events. Chicago’s Metromix put it succinctly: “It’s a gorgeous meditation on the sorrow of finding everything you want and not knowing how to keep it.” It is about Ennis, about a slow ache that nags and builds and finally gives way to honest grief when it’s far past the time he could have done anything to change it, if, indeed, he had ever had the will.

There is a series of scenes that are key to the final revelation and show how deceptive is the telling of this story, how subtly the thing is put together. I’m not going to apologize for discussing them, because I don’t think it will ruin anything: even though I knew what was coming at the end, it was still like being hit in the gut. In one of their early roughhouses on the mountain, Jack gives Ennis a bloody nose, and then stanches the bleeding with his own shirt; Ennis’ shirt, of course, is bloody as well. Later, as they are packing to leave, Ennis makes an offhand remark, almost lost in the activity, that he can’t believe he left that shirt behind on the mountain. When he visits Jack’s parents, he discovers Jack’s shirt in a narrow space behind the closet, bloodstains and all, with his shirt inside, “the pair like two skins, one inside the other, two in one.” We see the first crack in Ennis, no temper, no violence, just unfathomable sadness as he clutches the shirts to him as though he could take them inside himself. The final scene, in Ennis’ trailer, reveals the shirts on a hanger inside the closet door, next to a postcard of Brokeback Mountain, Ennis’ shirt now on the outside, holding Jack’s shirt safe: the closet door has become a shrine. Then we see Ennis’ face, barely hear his whisper, an almost silent cry from deep in a well of infinite loss.

The publicity line is “Love is a force of nature.” It becomes more than a catch phrase.

(Focus Features and River Road Entertainment, 2005)