The story of Amadeus is by now fairly well known. From a screenplay by Peter Shaffer based in turn on his original stage play, the film is told in flashback from the viewpoint of Italian composer Antonio Salieri, who lived and worked in Vienna as Court Composer to Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria. We meet Salieri in the film’s opening scenes, just after he has screamed “Mozart! I killed you!” into the Viennese night and attempted suicide. The opening credits roll, accompanied by the forceful strains of Mozart’s Symphony No. 25 in G minor, as Salieri is taken to the sanitarium. There he is visited by a priest who comes to hear Salieri’s confession, and it is this confession that forms the film’s narrative and the root of Salieri’s agony. Before telling his tale, he picks out a few of his own tunes on the harpsichord, tunes that thirty years before had been all the rage but now are completely unrecognized by the priest; then, however, he plays the opening strains of “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik”, which the priest recognizes instantly. Salieri, the once-famous composer, has slipped into obscurity while Mozart, the genius long dead, has achieved musical immortality.

As a boy and later as a young man, Salieri is deeply religious with an equally deep love of music, and his greatest desire in life is to serve and exalt God through his music. (As he composes, he glances up at a crucifix and thanks God when he completes a phrase.) Thus, when he learns of the arrival in Vienna of his time’s greatest musical prodigy — indeed, perhaps the greatest musical prodigy of all time — he is impelled to come see this person whose name he has always known.

This person is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Salieri’s curiosity and reverence turns to shock when he realizes that this man in whom flowers the greatest musical gifts imaginable, gifts far beyond Salieri’s own, is a crude and offensive person with a cackling laugh and a predilection for scatological language.

Amadeus thus sets up the dichotomy that will, in the end, destroy Mozart: the great genius’s own inability to relate to others, versus Salieri’s loathing of the man whose gifts so vastly and (in his eyes) undeservedly dwarf his own. Salieri uses his own influence to hinder Mozart’s career at nearly every turn, throwing up roadblocks before the little man that fuel the great genius’ descent into his own faults — his drinking and complete inability to manage money, to name just two. And then Salieri hatches his most insidious plan: to commission a Requiem Mass from Mozart, and then to kill Mozart and steal the Requiem to perform as his own work at the composer’s funeral. The film plays out like a Greek tragedy with dual tragic heroes: first Mozart, who is blessed with so much talent but no ability to manage a life, and later Salieri himself, who has been blessed with only enough talent to recognize the genius he so covets in someone else.

It is worth noting that, although this business with the commissioning of the Requiem and the plan to steal it is historically based, it was not actually Salieri who perpetrated this plan but another minor Austrian nobleman. The film is not actually intended to be a historically-accurate portrayal of Mozart’s life, but in Shaffer’s words, “a fantasy on themes in Mozart’s life”.

Amadeus is one of the most superbly-executed films I have ever seen. Photographed in Prague, a city whose present-day look has not changed much in two hundred years and is thus the perfect locale to double as 18th-century Vienna, the film’s sense of period is exacting in almost every detail. We see the opulence of the Viennese court, with its powdered wigs and lacey, ballooning garments. But in addition to this opulence, we also see some of the squalor of “lower” Vienna: first in the sanitarium, with the insane literally locked in cages or chained to the walls, and later in the mass grave in which Mozart is interred. Then there are the spectacularly-staged opera scenes, complete with effects of smoke and tumbling walls and demons bursting from the floor and such. Director Milos Forman keeps the film moving right along, so this 18th-century costume drama complete with lengthy opera scenes clocks in at 160 minutes and yet feels as if it is only half as long.

The acting is also outstanding. F. Murray Abraham, the film’s anchor, makes Salieri both loathsome and sympathetic. So convincing is his portrayal that I occasionally had to remind myself that he is actually the villain of the piece, which is precisely the point; it highlights Mozart’s inability to recognize those who were not acting with his best interest at heart. This “shifting sympathy” that Abraham is able to create is most clear in the scene, late in the film, when Salieri assists the weakening Mozart in composing the Requiem. I was almost convinced, as Mozart is convinced, of the selflessness of Salieri’s task — until he gasps with horror when Constanze, Mozart’s wife, gathers up the pages of the Requiem and locks them away, thus foiling his plan. Abraham won a much-deserved Oscar for his work here, over his fellow nominee Tom Hulce, who plays Mozart with almost equal skill. Mozart’s obsessiveness with his own music, his impatience with those whom he knows to be his musical inferiors, his earthiness and his tendency to insult without even considering the possibility that he may be doing so — all these qualities shine in Hulce’s portrayal. The supporting players are all equally fine, especially Jeffrey Jones as the Emperor and Elizabeth Berridge as Constanze Mozart.

Lastly, no discussion of Amadeus would be complete without mentioning the music. Appropriately, it is Mozart’s music that dominates the film, with the selections chosen as much for their dramatic impact as for their beauty. The musical performances in the film achieve as great a degree of excellence as the rest of the production. Sir Neville Marriner, one of the world’s premiere interpreters of Mozart, conducts the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, one of the world’s finest chamber ensembles; and while most films are scored after shooting has been completed, in the case of Amadeus the music was done first. The musical selections, taken from one of the most diverse bodies of music ever created by a single individual, not only accentuate and complement the screen action, but they form an aural portrait of the artist at the film’s center.

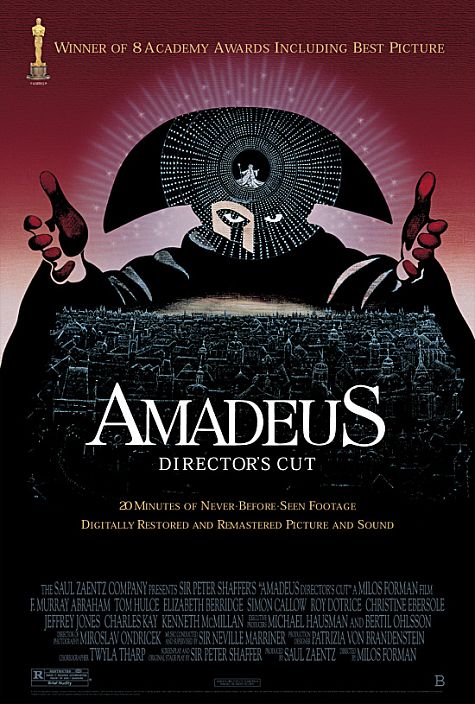

The film’s DVD presentation doesn’t include any special documentaries, but there is a music-only track without the dialog, and a number of special on-screen commentaries about the film and about Mozart’s life. There is also a listing of all the awards won by Amadeus, including the Academy Awards (Best Picture, Best Actor — Abraham — and Best Director, most notably).

(Orion Pictures 1984)