There is something to be said for walking into things without foreknowledge. I readily admit that a background in any area will help you to enjoy something more fully, but when it comes to specifics, it’s often better to have no expectations. I had heard a little bit of buzz, most of it favorable, about Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men; I don’t know if I would have been better off without it or not.

There is something to be said for walking into things without foreknowledge. I readily admit that a background in any area will help you to enjoy something more fully, but when it comes to specifics, it’s often better to have no expectations. I had heard a little bit of buzz, most of it favorable, about Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men; I don’t know if I would have been better off without it or not.

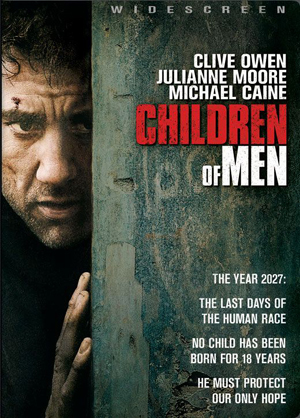

In its bare essence the film is a dystopian thriller (no, that’s not an oxymoron — there have been many.) The dystopian part hinges on a relatively recent catastrophe: people are infertile. It’s a world-wide phenomenon and has lasted for some eighteen years. (One may be of two minds whether this is a catastrophe or not.) Governments have toppled, nations come unglued, and in Britain, one of the few states that maintains any order at all, all immigrants are now illegal and mass deportations are in progress. As the story opens, the world’s youngest person has been killed in a riot, reportedly sparked by his spitting in the face of a fan. As it turns out, this is irrelevant to the story. Theo Faron (Clive Barker), a disgruntled agent for an unspecified government agency, is contacted by his ex-wife, Julian (Julianne Moore), for help in obtaining travel documents for a very special person, a young woman, Kee (Claire-Hope Ashitey), who is pregnant. Julian is trying to get her out of the country to a group called the “Human Project,” where she can be cared for and, hopefully contribute to a remedy for humanity’s great affliction. Julian’s organization, which is really nothing more than a terrorist group, has other plans. With one thing and another, Theo winds up escorting Kee to the coast, where they break into a refugee camp to make their escape.

An acquaintance referred to this film in conversation as “threadbare,” which seems to be as apt a description as any. It’s a gray film — not gray as in “shades of gray” or in the sense of murky motivations (although there is great potential for that), but just a cloudy, drizzly, roll-over-and-go-back-to-sleep gray.

The basic premise, universal infertility with mysterious causes, is perhaps arbitrary and extreme, but that’s no disqualification for making a good story to a hardened veteran of science fiction. One need only recall J. G. Ballard’s “Catastrophe” novels to see how well it can work. One can even get away with a bare story line if there is sufficient passion, politics, or at least penetrating psychological insights. It’s a basic situation and plot that have great potential for high drama, poignant irony, extreme tension, even comic relief.

None of that happens.

What happens is that this gray little movie goes flat after about fifteen minutes and never recovers. Even a star turn by Michael Caine can’t liven it up. I’ve seen Caine’s cameo called “brilliant,” and it probably is. It’s also the sort of thing Caine can do in his sleep. In fact, that might apply to the entire cast: they all fine actors. I just don’t think they were terribly involved.

(An explanatory note: I am an avid audience. I can sit through just about anything, including a six-hour dress rehearsal of Siegfried, and not only never twitch but get really caught up. I only walked out of one movie in my entire life, a pathetic soft-core attempt at the story of St. Sebastian, and even that was almost at the end. If I can’t get involved in what’s on the screen or stage, something is seriously amiss.)

I had considered for a moment the idea that those who don’t know genre should not try to do it as a possible explanation for why Children of Men misses so badly, but I’m not sure that’s germane. (P. D. James, who wrote the original book, writes mysteries. That’s not the same.) It really seems to be more a matter that all the parts, or at least most of them, are there and they never quite get put together. The film, as I noted, opens with the news story of the death of the world’s youngest person, which Theo sees in a coffee shop (a generic Starbucks clone — it may even be a Starbucks, but who noticed?) as he’s picking up a latte or some such on his way to the office. Within two minutes after he leaves, the coffee shop explodes. Nothing develops from that, unless it is supposed to be a hint about Julian’s organization and its activities, but there’s no real connection made. Similarly, the final scene, which holds huge potential for tragic irony, leaves one with the feeling of “And your point was?”

I left a sense that Children of Men tried to be many things, and wound up being none of them.

(Strike/Universal Studios, 2006) For full credits, see the listing at IMDb.