Every book is a grimoire, a witch’s recipe book for summoning thoughts and feelings, travels and transformations. Books of different genres can be used to invoke different seasons: horror for the haunted harvest time of late autumn, mysteries for the long nights of winter, and ghost stories to accompany the thunderstorms of spring. But fantasy — with its bewitching call to be out and away — is for summer. One June day you may open a book of fantasy stories and notice that, as if dried petals had been pressed between its pages, the faintest scent of roses begins to stir upon the air, banishing the last memories of wool socks and raincoats. Your senses begin to awake, slowly noticing that wisps of birdsong and tendrils of soft breezes have come curling like magically growing vines through the crack of a half-open window, inviting you to escape.

Every book is a grimoire, a witch’s recipe book for summoning thoughts and feelings, travels and transformations. Books of different genres can be used to invoke different seasons: horror for the haunted harvest time of late autumn, mysteries for the long nights of winter, and ghost stories to accompany the thunderstorms of spring. But fantasy — with its bewitching call to be out and away — is for summer. One June day you may open a book of fantasy stories and notice that, as if dried petals had been pressed between its pages, the faintest scent of roses begins to stir upon the air, banishing the last memories of wool socks and raincoats. Your senses begin to awake, slowly noticing that wisps of birdsong and tendrils of soft breezes have come curling like magically growing vines through the crack of a half-open window, inviting you to escape.

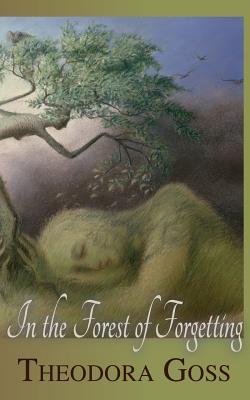

Theodora Goss’s new collection of sixteen short stories recalls that early summer scent of roses. While a number of these stories have been published previously in such venues as the print zine Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet or Strange Horizons, most readers will find these stories as delightful a discovery as the first days of summer.

Goss’s literary style and subjects are reminiscent of some of the best fantasists, including E. T. A. Hoffman, Angela Carter, and Joan Aiken. In part, these influences are invoked by Goss’s settings of Victorian society and Old European cities plundered for their most poetic and gothic elements. Art, architecture, and music haunt the characters of these stories like the subjects of Pre-Raphaelite works of art. The magic of these stories, however, is preoccupied with matters of practical magic, including those domains usually dismissed as “women’s work.”

The title story, “In the Forest of Forgetting,” is a case in point. While many of the other stories in this collection are, like summer roses, filled with extravagant detail, the simplicity of this story lingers like the scent of dried herbs through winter. Goss uses the archetypes of fairytales — the dark wood, the witch, the knight, the apprentice — and works them into something more, the memoir of a woman with breast cancer. This remains the thread which weaves together all the stories in this collection: no matter how familiar the trope or archetype, Goss demonstrates how such images can be used to illuminate the realities of our modern lives. War, prejudice, the struggle to express creative imagination and identity — these are the true subjects of Goss’s work. At times, as in “The Rose In Twelve Petals,” the characters are the sort of silly and pretentious small-town “nobility” one expects to find in a Georgette Heyer novel, vengeful ex-lovers and snobby old ladies staring at one through their lorgnettes. Yet these are fairytales for adults, where objects such as a falling tower, a stray dog with a mangled paw, or a temple singer rendered mute serve as portents of violence and pending catastrophe which come to one like half-heard fragments of news from a distant radio.

A number of stories, such as the animal bridegroom story, “Sleeping With Bears,” hint at how imagination, like wild animals, can imperil the complacent fictions of family and society. “Pip and the Fairies” is another of these stories, tugging insolently at the hem of the gauzy-winged fairy garment of children’s literature itself. Philippa, the main character, is the grown-up child of a famous children’s book writer, and her own questions about her mother’s books, featuring the child protagonist Philippa (Pip), are a sort of allegory of fantastic fiction, underscoring the different purposes and interpretations that adults and children have for such fiction. The grown-up Philippa’s memories of her real life as a child and how it conflicted with the romantic retelling her mother shaped into her own stories are a gentle reminder that it is the child who is often more concerned with the desperate needs and fears of survival, such as food, money, and abandonment. Such an allegory could well weigh down a story with heavy-handed prose or smug preachiness, but this tale, like the rest in this collection, remains true to the best fairytales and fantasy literature in that it operates both as a simple and elegantly-told story and as a more complex exploration of the form.

Goss has also created a trio of stories, reminiscent of Milan Kundera’s work, which connects the freedom to express creative imagination with personal and political freedom. “Professor Berkowitz Stands On the Threshold” is a strange but fascinating story about those artists and scholars who dwell at the margins of canon. “Letters from Budapest” is a variation upon the trope of the Muse incarnated in a living woman (though this description does not do justice to the complex interweaving of the theme of creativity as a form of resistance to the clichéd slogans of both Fascism and the middle class). “The Wings of Meister Wilhelm” is a sort of reverse Icarus tale, where a young girl only just beginning to realize the hypocrisy of adults helps a stranger in town to build a set of mechanical wings.

My favorite tales in this collection, however, are a pair of stories featuring a mysterious character known only as Miss Emily Gray. “Miss Emily Gray” unfolds like a magic spell, showing us all the ingredients and the proper chronology for the steps, but saving the final secret ingredient for the ending, which provides a haunting new twist on the wicked stepmother trope. “Lessons With Miss Gray” brings together a number of the characters seen throughout the collection. This final story does not so much weave all the stories together as suggest that all stories illuminate one another, intersecting and affecting one another like a musical motif or an assortment of faded photographs found together in an old tin. We have seen some of the young girls in this last story in previous stories, but it is only in this last tale, evocative of Joan Aiken at her best, where we realize that wishes really can be horses, but they are, at best, wild horses difficult to bridle, and as likely to cause destruction as to offer a means of escape.

Perhaps I have read too much into these stories. They are, after all, merely fairytales, stories told to amuse. The meanings you take from them will be your own, though perhaps you will also find some whispered secret in the voice of the rose. “The rose can tell us, but it will not. The wind sets its leaves stirring, and petals fall, and it whispers to us: you must find your own ending.”

(Prime Books, 2006)