William P. Simmons wrote this review.

William P. Simmons wrote this review.

Satan, Lucifer, Old Scratch: no matter what you call him, the Devil has been a central character in Western literature since the first man rebelled and the first heart broke. Liar, tempter, and stealer of souls, Satan holds the realm of mortal affairs in his crafty grip, ruining souls with the ease of a malicious kid marking muddy hand prints across the curtains.

Cut on in, I’m sure you’ve heard this song. Through the ages, in both sacred and secular text, no character has earned the scorn, contempt, hatred, or fear that the Devil summons. Whether associated with the Fall or credited with modern damnation, his is a history and future of pain, disgrace, and shame.

Or so the Judaic Old Testament suggests, and the popular media has confirmed through print and film, weaving before audiences techno-color nightmares with decadent luster. But, what if, gentle reader, you found the gospel had misled? Have none of you sympathy for the devil? Hold tight, you will before the last wonderfully elegant sentence of this novel lifts its spell.

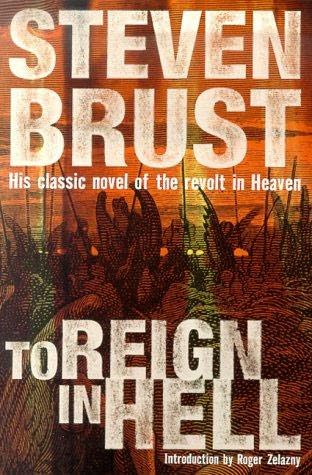

With a dark charm and grace no less endearing and seductive than the prince of darkness himself, To Reign in Hell, by Steven Brust, is a deliciously decadent voice leading you off the same tired, beaten path and into the wilderness of primal miracle and possibility. With a premise and daring vision that would have undoubtedly landed him on the Inquisitor’s table in an older time, the author of this descent into epic struggle manages with a deft and authoritative hand to slap an ancient myth in the face and force it on its head.

Combining characters and themes from biblical myth, cross-cultural folklore, and literature, the book offers an alternative telling of the war between God and Satan, lords of light and dark. That Brust manages to avoid the tired cliche of empty moralization is an enormous feat in itself. That he makes us finally care for characters that we have too long read with a rigid one-dimensional and abstract distance makes me recommend it with fervor and enthusiasm. This is not a diluted bible-school miracle play, but a gripping, three-dimensional examination of soul and possibility.

The hero? You guessed it! A personable, highly believable, and sympathetic Satan whose very integrity of soul and steadfast value of honesty makes him a target of a heaven deceived by Abdiel, a trickster figure worthy of the grim, wicked Loki in Nordic mythology. It’s interesting to note that a rigorous introspective attitude and desire to only do what is best for Heaven results in Satan’s woes, not the errors of hubris, lust, or envy that have been customarily tacked onto him like bad clothes. A romantic hero (or anti-hero if you prefer) of the highest sort, the Satan of Brust’s uncertain, imperiled cosmos is easily the character we empathize with most as he struggles against misunderstanding, tyranny, and the fate forced upon him by friend, foe, and circumstance.

Beginning in (of all places!) the beginning, chaos turns against itself and forms something akin to life. God and Satan are the first ones, wielding and shaping the “flux,” the essence of order and creativity, from primordial destructive energy. More by accident than design, other beings are created from the First Wave (a term used to describe moments when chaotic force reasserts itself to wreak thoughtless havoc), and after much effort, create through force of collective will a physical boundary outside of cacoastrum, a place where they may survive until the next outbreak erupts.

Fascinating is the concept of a force of chaotic energy that threatens survival, the stuff of life deriving from the very eruption of blind violence. Through the second and third Waves of this chaotic energy, newer generations of beings (go ahead, call them angels) are created, and in each successive attack waged blindly against their safe haven by the universal flux, victims unable to resist or keep the primal force at bay are destroyed or transformed.

A plot driven by desperate need, the pain of mistaken intentions, a growing sense of mistrust, and power thirst unravels with a sleek fluidity that makes the mounting tragic events almost painful (oh, but so addictive) to witness. Yaweh has a plan to forever preserve his kingdom and fellows. Through the collective, aimed will of all of Heaven’s inhabitants, he wishes to defy the chaotic flux by creating a dimension of space and substance that will be forever independent and resistant to it.

A noble goal, and one which Satan is asked to aid in. As sort of a celestial foreman, Satan is to ensure that all the younger angels do what is expected of them, handing out discipline to those who defy the plan. You see, Yaweh’s plan has a little flaw, namely that thousands of angels, particularly the ones formed by the last few waves of universal “flux,” will in all probability be destroyed. Soon the alert reader notices the classical biblical themes of order and rebellion swarming amidst scenes of intrigue and palace-like conspiracy. Abdiel, one of the younger members of Heaven, shares a growing fear of Yaweh’s plan, and in typically underhanded fashion, devises a scheme to use Satan’s uncertainty and reluctance to ally himself with the great re-shaping to build a rift between the greatest forces in the kingdom.

With the finality and pathos of Tragedy, well placed deceptions, errors in judgement, and coincidence turn friend against friend as revolt explodes like a thunder clap. Such is the grace and power of the author’s characterization that you actually care about these characters, you feel as if you were beside them, sharing a personal stake in the result of their predicaments. Losing valuable sleep because the damned (bad pun intended) thing kept me up, I particularly empathized with Satan, a figure whom Brust makes more lordly than the lord, so caring as to make you feel ashamed at the treachery and apathy with which his old friends (most notably God) treat him. Although I knew from page one how the traditional tale was going to end, I had no idea when turning the pages to what a great extent I would empathize with the Devil, cheering him on like a demented cheerleader.

The difference between the two most obvious figures in this drama is wonderfully highlighted near the book’s end. After Abdiel’s treachery has been exposed, God is brazenly, unrepentantly depicted as a figure who has begun to believe his own propaganda. Although he is largely responsible for the bad blood staining what he claims is his kingdom, his own pride (and newly acquired taste for authority) makes it impossible for either himself or Satan to heal the rift between them . . . and that’s all I’m going to tell you, by Lucifer! You think you know what occurs next? Perhaps, but do you know how?

Although the author’s word choice is at times archaic, and his style formal in the way that biblical texts, classic myths, and Middle-English epics read, it is a purposeful choice that makes the subject matter and larger-than-life characters all the more believable and engaging. A much better read than much of the material on which it was based, To Reign In Hell displays a fullness of characterization and complexity of theme lacking in many traditional depictions of these universal symbols. Because they are multifaceted personas that feel, bleed, and struggle, we see in their conflicts and joys reflections of our own. Before we know it, their story becomes our story, and like the angels of said title, we find ourselves taking sides while wishing we didn’t have to.

(Tor, 1984)