The first question that occurs to me when I encounter a book by Steven Brust is “What is he up to now?” With Brust one can never be sure, except that it’s going to be fun. It might be a take-off on twentieth-century American detective fiction (the Taltos Cycle, which features a hero too much like Archie Goodwin to be coincidental), or on science-fiction’s New Wave (To Reign in Hell, an homage to Roger Zelazny), or an affectionate parody of nineteenth-century swashbucklers (The Khaavren Romances). (And when I say “take-off,” I mean styles and modes as much as story elements, maybe more.) But, whatever he does, there is always something distinctly and uniquely Steven Brust about the end result.

The first question that occurs to me when I encounter a book by Steven Brust is “What is he up to now?” With Brust one can never be sure, except that it’s going to be fun. It might be a take-off on twentieth-century American detective fiction (the Taltos Cycle, which features a hero too much like Archie Goodwin to be coincidental), or on science-fiction’s New Wave (To Reign in Hell, an homage to Roger Zelazny), or an affectionate parody of nineteenth-century swashbucklers (The Khaavren Romances). (And when I say “take-off,” I mean styles and modes as much as story elements, maybe more.) But, whatever he does, there is always something distinctly and uniquely Steven Brust about the end result.

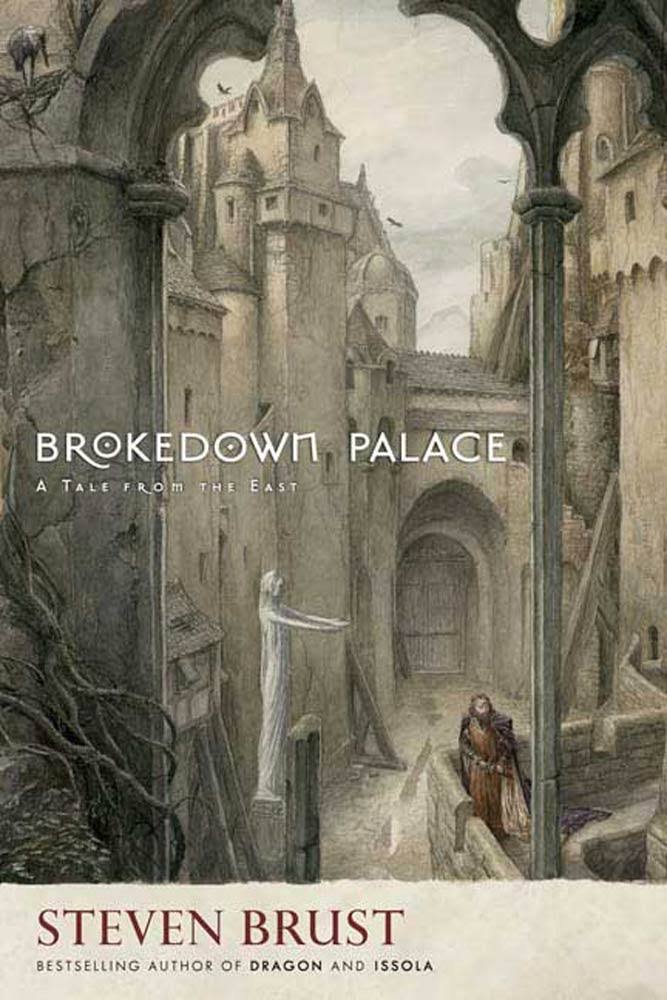

In Brokedown Palace, the field of play is the folk tale. The story itself is a simple one, about four princely brothers in the kingdom of Fenario. Readers of The Taltos Cycle will immediately recognize the name and the universe, although this story seems to take place many years before Brust’s works about the Dragaeran Empire — at least it has that feel of antiquity to it. The brothers — King László, Andor, Vilmos, and Miklós — live in the Palace, which has stood in its present form for some four hundred years. Other things stood there before, beginning with the hut of the nearly legendary King Fenarr and the successive palaces and fortresses that have occupied that site. At any rate, that place has been important in Fenario for a long time. László has a very fast and extreme emotional reaction whenever anyone mentions the condition of the palace, which is not very good; Miklós, the youngest brother, has a habit of pointing out reality to those who prefer to ignore it. (I should point out that Andor seems to lack purpose in life, while Vilmos, who is large enough that his tread sets floors to reverberating and walls to quivering, would prefer not to be involved.) Add in a taltós horse who goes by the name of Bölk and seems to know much more than anyone else about what’s going on; Viktor, Captain of the Guard, ambitious and not too far removed from the throne himself; Brigitta, who has been the king’s mistress, and whose own heritage has some mystery to it; and the Demon Goddess, whom you will all remember from stories of Vlad Taltos, and you have an interesting mix.

I’m going to do something that I do quite often, and that’s not talk about the story very much, because the other things that are happening here are just as interesting, and if you want a plot outline, you can get it from the back cover.

First, as Brust says, “A novel is a framework on which to hang the greatest amount of cool stuff.” (My paraphrase.) He’s certainly done that here. For starters, the book begins with the legend of King Fenarr (who, strangely enough, also kept company with a taltós horse). The narrative is also relieved from time to time with further folktales (and I would be inclined to take them as genuine Hungarian folktales, complete with the kind of tagline I’ve seen in folk stories from Sicily to Denmark to Siberia to the Southeastern U. S. that can be rendered as the generic “once upon a time,” except that these tales are so perfectly suited to illuminating the story). Remember, please, that Brust is the master of the digression, and these interludes meld perfectly with the ongoing plot, providing not only some backstory but also some revelation of events that the characters don’t know about. I think this may be the only time I’ve seen Brust tailor his digressions so tightly to the story line. The narrative as a whole takes on the character and tone of a fairy tale, with that kind of spiky and distanced diction and the sense that something magical is looking over your shoulder as you read.

And yet this is a novel, with all the elements that make a novel what it is. I’ve said before that I think Brust is one of the master stylists working in fantasy today, and this one only confirms that opinion. Even though Brust is describing fantastic things, his mode is realist narrative, and a very clean and spare narrative it is, although more poetic than most of his work. While his characteristically sardonic humor and his flair for irony are readily apparent, there is a magical feel to it, in the sense of things that cannot be, and perhaps should not be, explained.

As tends to happen with very good books, Brokedown Palace is much better than my recollection of it. It’s somehow richer and more subtle than most fantasies, even Brust’s other works.

OK — this is not your “normal” Steven Brust novel. Read it anyway.

(Ace Books, 1986)