Let’s face it, much modern fantasy is duller than dirt these days. That’s not a reflection on the technical level of the work (which, in many cases, is higher than it has ever been) but rather a sad commentary on precisely how many times we’ve seen this all before. Plucky young boy (bonus points if it’s a plucky young girl, double bonus points if she dresses up like a boy, falls in love with a manly hero and earns his respect with a sword before swapping her breeches for more ladylike attire) overcomes low self-esteem and local bully, picks up sharp pointy object, saves world from unnamable ancient evil that really ought to know what to watch out for by now, and lives happily ever after until the fans demand a sequel. Add two helpings of talking critters (Take your pick from A) dragons, B) horses, C) unicorns, D) telepathic cats or E) all of the above), shake well, season lightly with modern philosophy and there you have it: Book One of The Road To Elfenstuff Trilogy, which no doubt will expand out to ten or twelve books in the fullness of time. It is, to quote a comics writer talking about his least-favorite character, not “real good or real bad or real interesting.” It is, however, dependable and it delivers precisely what the cover art promises, and as long as there are folks out there who enjoy that sort of thing, more power to them.

Let’s face it, much modern fantasy is duller than dirt these days. That’s not a reflection on the technical level of the work (which, in many cases, is higher than it has ever been) but rather a sad commentary on precisely how many times we’ve seen this all before. Plucky young boy (bonus points if it’s a plucky young girl, double bonus points if she dresses up like a boy, falls in love with a manly hero and earns his respect with a sword before swapping her breeches for more ladylike attire) overcomes low self-esteem and local bully, picks up sharp pointy object, saves world from unnamable ancient evil that really ought to know what to watch out for by now, and lives happily ever after until the fans demand a sequel. Add two helpings of talking critters (Take your pick from A) dragons, B) horses, C) unicorns, D) telepathic cats or E) all of the above), shake well, season lightly with modern philosophy and there you have it: Book One of The Road To Elfenstuff Trilogy, which no doubt will expand out to ten or twelve books in the fullness of time. It is, to quote a comics writer talking about his least-favorite character, not “real good or real bad or real interesting.” It is, however, dependable and it delivers precisely what the cover art promises, and as long as there are folks out there who enjoy that sort of thing, more power to them.

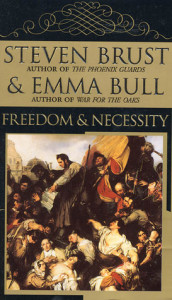

However, there are enough fantasy authors out there intent on sidestepping clichés to keep readers who crave something different and challenging on their toes. Chief among their ranks are Steven Brust, who had the chutzpah to go Milton one better in To Reign in Hell, and Emma Bull, whose War for the Oaks ever more clearly revealed these days as one of the cornerstones of modern low fantasy. Put the two of them together on one project and the safe money is that the book is going to be witty, urbane, fast-moving and utterly fearless.

Thankfully for readers of Freedom & Necessity, the two authors’ collaboration, the safe money is right this time. The book, while completely unexpected in its content, delivers on all the implied promises its authors have made with careers of sustained excellence. It’s just that Freedom & Necessity, perhaps inevitably, does so on its own, very demanding terms.

For starters, the book is that terror of English majors everywhere, an epistolary novel. Depending on how one classifies Bridget Jones’s Diary, the form hasn’t been used well in the genre since Stoker took it for a spin in Dracula, and the format itself is enough of a challenge for readers who were expecting a more straightforward narrative. On the other hand, the epistolary format allows for multiple perspectives on the events of the plot from all four of the main narrators, all of whom bring something unique to the table. A story told from any one of their viewpoints, or from an omniscient one, would take away much of the pleasure of unraveling the novel’s mysteries as the characters do so themselves. The joy of discovering what’s really going on is only part of the book’s enjoyment; the rest is in seeing how the characters do so in their own ways.

Which brings me to the characters and the plot. The story at first is a fairly simple one. Dashing young hero James Cobham has an accident at sea and is presumed drowned, then shows up two months later with no memory of where he’s been or what he’s been doing. Judging discretion to be the better part of valor, he remains mostly incognito while slowly trying to understand what precisely happened to him. These efforts draw in the other three primary narrators of the book: stolid Richard, flighty Kitty and adventurous yet solid Susan, all of whom are related and/or tied to one another in some fashion or other. (Detailing the actual relationships would spoil half the book’s surprises, so I leave them giftwrapped for you to explore.) However, each voice thankfully hits more than one note, else the epistolary trick would soon have grown unbearably dull. For example, Kitty (whom the reader is initially inclined to dismiss as a sort of period ditz) uncovers some of the key elements of the vast conspiracy James was once a part of, even as she seemingly focuses on inconsequentialities like drapes and furnishings. And so, across England our protagonists go, pausing only to scribble extensive letters to one another about love, Hegel, labor philosophy and the just-might-be occult conspiracy that the father of James may or may not be leading. To say more than that of the story is to risk revealing it all. Let it instead suffice to say that there is enough derring-do, romance, period detail (yes, Engels does stop in for a rather flattering cameo), Crowleyesque mysticism and human sacrifice (in a manner of speaking) to keep things moving along at a merry pace. Readers are advised, however, to pay very close attention to the details of the climactic scene, which is of the blink-once-and-you-miss-it variety.

There’s so much going on in the book that unless you make sure you’re looking at the right place at the right time, you may find yourself three pages past the climax and wondering what the heck happened to bring everyone to their current states.

Brust’s biggest gift as a writer has always been whipcrack-fast dialogue, and it does not desert him here. James, who echoes the voice of the better-known character Vlad Taltos, is as fast on his feet, devastatingly witty and Byronically brooding as one might wish a period hero to be. What is more of a pleasant surprise is that Bull, whose strength has always seemed to be more in other aspects of character and setting, matches him line for line and letter for letter. It is a joy to read these two stylists, at once in contrast and working together, driving one another to better themselves from letter to letter.

So is Freedom & Necessity worth it? Indubitably. Fans of both authors earlier work may be a bit surprised at the lack of familiar terrain, but the pleasure of exploring the new ground presented here is a worthy substitute. Particularly cautious readers may wish to brush up on their Hegelian thought and Chartist history before plunging in, but even those who think that Marx was that guy who made the duck come down when someone said the magic word will find plenty to enjoy here. Dive in; both the murky waters of conspiracy and the clean air of a remarkably enjoyable book are waiting for you.

(Tor Books, 1997)