Samuel R. Delaney’s Dhalgren was originally published in 1974. It was brash, it was overtly experimental, it was greeted with everything from wild hallelujahs to roars of outrage. It was in many ways the culmination of science fiction’s New Wave: where writers such as Aldiss, Ballard, Disch, Zelazny, and Delany himself had pushed the envelope, Dhalgren finally ripped it up and scattered the pieces. Mainstream critics, caught flat-footed, came up with the term “magical realism” in an attempt to link it to “respectable” if someone outré writers such as Borges and Garcia Marquez. Given their historical and tightly held look-down-the-nose disapprobation of science fiction, there wasn’t much else they could do.

Samuel R. Delaney’s Dhalgren was originally published in 1974. It was brash, it was overtly experimental, it was greeted with everything from wild hallelujahs to roars of outrage. It was in many ways the culmination of science fiction’s New Wave: where writers such as Aldiss, Ballard, Disch, Zelazny, and Delany himself had pushed the envelope, Dhalgren finally ripped it up and scattered the pieces. Mainstream critics, caught flat-footed, came up with the term “magical realism” in an attempt to link it to “respectable” if someone outré writers such as Borges and Garcia Marquez. Given their historical and tightly held look-down-the-nose disapprobation of science fiction, there wasn’t much else they could do.

In basic terms, Dhalgren is a bildungsoman, the coming-of-age story of a young man, known only as “the Kid,” who has forgotten who he is. He comes to Bellona, a large city somewhere in the central U.S. that has suffered its own local and highly specific apocalypse, the causes of which are never explained. Nor, for that matter, are the actual events of that disaster ever described. It’s now a creeping ruin with perhaps a thousand inhabitants, largely composed of those who had no way out and nowhere to go to begin with (which, in post-Katrina America, has become not as remarkable as it should be). The Kid goes through identity after identity — wanderer, day laborer, gang leader, poet — always in search of his name.

It’s presented as an edited manuscript (but not immediately — like most everything else in the story, this is something that makes its way into view eventually), except for the last section, “Anathemata: a Plague Journal,” which takes on the character of the notebook the Kid finds and in which he writes his own poems, in the spaces left by someone else’s journal, complete with elisions, author’s comments and marginal notes. (Or perhaps it was someone else’s notebook: we gradually become unwilling to accept that fact along with numerous others as reality becomes less sure of itself).

Time is not bound to any objective standard. The Kid loses blocs of time, minutes, hours, weeks. Events repeat, sometimes openly, sometimes in disguise. Some characters can’t deal with the reality depicted in the story, but we are often unsure exactly what that reality is, or when things happened, if they actually happened.

“Otherness” is a recurring theme in science fiction in general, and Delany has broken that broad concept into its components, running a gloss on the varieties of “other” — race, sex, orientation, religion, class, history — and the ways they intersect to form identity, the core of the book. There is, for example, a strong current of sex in the book, and it’s instructive that the first two events are the Kid’s pursuit and sexual encounter with a woman who turns into a tree and with a man who treasures pain. Bisexuality is a given — the Kid falls in with a woman and then meets a boy who wants him, and they become a constant threesome. Sex becomes a metaphor for the variety of humanity, the means by which people come to know each other, a game, an exploration, an investigation into difference. Delany explodes the falsity around sex and it becomes as well something of a metaphor for Eden — innocent and value-neutral except insofar as it enables us to touch each other.

It’s not an “easy” book, nor, at just over 800 pages, is it brief. It is dense, with events, revelations, intuitions, insights, and a sensuality that is rare in fiction — not merely sexual imagery, but a full range of sight, taste, smell, sound, a density of sensation that is sometimes almost overpowering. The narrative is broken, circular, layered, fragmentary, and yet Delany’s prose is so clear and lucid that we are prone to accept everything he does. (Well, I was — my most frequent reaction to his formal adventures was “wow!”) Dhalgren has been called “pretentious,” which makes me wonder — What it if had not been marketed as science fiction? I don’t recall similar comments about Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, which was published in 1973 and to my mind is the closest analogue to Dhalgren within or without the boundaries of science fiction. It’s equally surreal, equally explosive, equally adventurous, and scarier. I take it as a reflection of the fact that self-aware artistry on this level is not something that science fiction was used to or prepared to cope with, nor, as I noted above, were “mainstream” critics ready for something this accomplished being presented as genre fiction. Let that be fair warning: we are no longer dealing with “science fiction” that comes anywhere close to the type specimen. We are entering new territory that draws on all of literature for its themes and devices and leaves Gernsback’s dream far behind.

In many ways I see it as a forerunner, perhaps even ancestor, of contemporary renegade “genres” such as slipstream. (There are many other possible antecedents, of course, going all the way back to J. G. Ballard and beyond.) Mostly, and it’s ironic considering the thematic thrust of the novel toward searching for answers, it’s because Delany, while rejecting consensus reality, or even the idea of consensus reality, doesn’t explain anything of the context, which I’ve found to be characteristic of those writers generally considered “slipstream,” such as Jonathan Lethem or Carol Emshwiller or Karen Joy Fowler. It’s a phildickian worldview (sorry, but I’ve been dying to use that word ever since I discovered it), mordant, dark-edged, treading the edges of sanity, and it’s just there and we have to deal with it, somehow.

Do you want to read Dhalgren? Not if you’re just interested in a Western with rayguns or a dystopian detective story. If, however, you are interested in understanding anything that came after — in Delany’s terms, to be aware of the protocols of the genre, which, I think, Dhalgren substantially recast — that is to say, any postmodern science fiction and most postmodern fantasy, you can’t afford not to. If it helps at all, I enjoyed it when, more or less clueless about the range of possibilities in literature, I read it thirty years ago. I enjoyed it more this time.

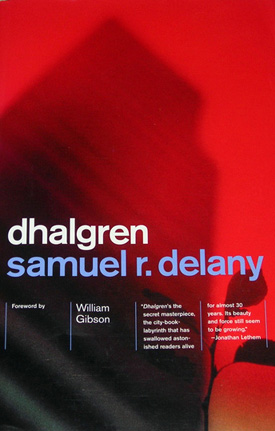

(Vintage Books, 2001 [orig. pub. 1974])