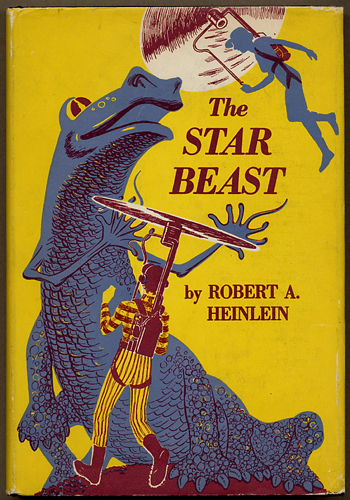

If I hadn’t already decided to finish reading the Heinlein juveniles, I might have been tempted to skip this one. The jacket copy describes some hijinks involving a boy and his pet alien, Lummox. The cover has a possibly pre-adolescent boy standing with a multi-tonne* dragon/elephant/mastiff, and the whole set-up just seems so young, like maybe his publishers wanted to cast a wider net by publishing a novel that straddles juvenile and children’s fiction.

If I hadn’t already decided to finish reading the Heinlein juveniles, I might have been tempted to skip this one. The jacket copy describes some hijinks involving a boy and his pet alien, Lummox. The cover has a possibly pre-adolescent boy standing with a multi-tonne* dragon/elephant/mastiff, and the whole set-up just seems so young, like maybe his publishers wanted to cast a wider net by publishing a novel that straddles juvenile and children’s fiction.

*I’m Canadian; we use metric.

After putting it off for awhile, I finally cracked the book open, expecting some Clifford the Big Red Dog-style adventures, and was taken entirely by surprise. Rather than one of Heinlein’s occasional (though usually still quite passable) literary misses, The Star Beast (which is 60 years old this year) turns out to be a hidden gem.

It starts out with the loveable Lummox, feeling neglected by his owner, John Thomas, whom is distracted by girls lately and doesn’t spend enough time playing with his pet or taking him for walks. So he carefully attempts to squeeze out a gap in the fence (ending up simply pushing it over by mistake) and goes wandering around the neighbourhood.

Since he’s basically a giant alien monster, before you know it his walk has turned into a parody of a Japanese monster movie, with tanks and helicopters and bazookas (none of which do anything more than tickle him). Once John Thomas is located he chastises his pet, takes him back home, and puts him back in the yard. This then leads to a court case wherein a representative of the Department of Space presides and makes a determination as to what action should be taken with the unruly pet.

But this then leads in turn to a rather serious political crisis, when it turns out Lummox is, in fact, a rather important representative of a hitherto unknown planet, the denizens of which might have to blow up Earth for their audacity in taking him away.

Every stage of the story follows logically from the next, but the reader could hardly predict what would happen next without prior knowledge of it. What’s most interesting about this story, to me, is that it’s not really about John Thomas. Oh, sure, he’s in it. He’s a fairly important secondary character. But Heinlein doesn’t stick with his perspective throughout the book. Instead, at least as much of the book takes place at the Department of Space, from the perspective of Mr. Kiku.

In a sort of future version of the United Nations, Mr. Kiku, undersecretary of the department of space, is almost certainly the most powerful government official on Earth, not that he’s ever able to enjoy it. Staying out of the limelight and working himself to the bone, this thankless and utterly necessary master diplomat is the one who keeps the world from being blown up on a daily basis. And Earth’s populace is blissfully unaware. Sound familiar?

Beating out the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by a good three decades, and Men in Black by over four, Heinlein didn’t just do this story first, he did it best. I’ve been enjoying the recent books in John Scalzi’s Old Man’s War series. The last few books have been much more about diplomacy than space battles, and are no less riveting for it. But who knew that Heinlein, the creator of the self-same military science fiction tradition which led to Old Man’s War, was himself quite capable of having his heroes save the day by talking and listening as well? (In fact, it’s positively Asimovian, in retrospect, but at the time this book was published, Isaac had only just started his Foundation series.)

And Mr. Kiku is a fantastic character. Always direct but fluent in reading nuance; incapable of having his feathers ruffled; wielding analytical reasoning like a honed weapon. Having a non-European-descended character in a starring role in a novel way back in 1954, before there was even a Civil Rights Movement, is awesome. But writing him the same way today’s better authors would, making no special note of his race relative to other characters, taking for granted that the world of the future will be one where skin pigment simply doesn’t matter, that’s amazing.

I could say more about Heinlein’s progressiveness when it came to racial equality. But Heinlein generally just wanted to write good characters, while rejecting the view that he had to limit his options to a particular colour palette. So Mr. Kiku is a great character, not a flashy political statement, and as a result, neither the character nor the story have aged poorly at all.

Instead let me close with a different thought. Heinlein really got away with something, and I’m not talking about the minority characters he snuck into his segregation-era books. No, what he got away with, this time, was sneaking a very funny, well-written adult story into a set-up that seemed more decidedly juvenile than usual. It’s the best example in my significant reading experience of why not to judge a book by its cover. What a treat this book turned out to be, indeed.

(Baen, 2012)