Jayme Lynn Blaschke penned this review.

Jayme Lynn Blaschke penned this review.

There are few things more depressing in life than to see brilliance punished. The fact that it happens with disturbing regularity makes it no less palatable, and when it happens to a writer as overwhelmingly talented as Patricia Anthony, it’s downright criminal.

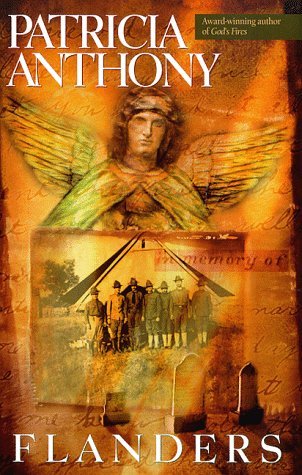

Flanders is, simply put, a marvelous work filled with bleak imagery and raw emotion that garnered wide acclaim and landed on many best-of-the-year lists when it came out. It also killed Patricia Anthony’s career as a novelist. Ace, her publisher, specialized in straightforward science fiction and struggled with the marketing of Anthony’s previous novel, God’s Fires. Flanders was, if anything, an even worse fit for that publisher, and things, as they say, went rapidly downhill from there.

But if Flanders was so good, why couldn’t it overcome those handicaps and find an audience? Well, it isn’t science fiction to start with. Not even close — unless one defines science fiction as anything that isn’t unambiguously mainstream. But that Flanders has both feet planted squarely in the fantastic, there is no doubt. Call it what you will — speculative, fantasy, supernatural or magic realism — the audience existed for this novel, and it’s a shame Ace didn’t look harder.

Those readers who do look hard enough will find the powerful story of Travis Lee Stanhope, a young volunteer from Texas serving with the British Army at the start of World War I. A philosophical, poetry-loving intellectual, Stanhope’s sharp mind opened doors and earned him a place at Harvard Medical School — and a way out of his troubled, hardscrabble life in West Texas. Harvard, unfortunately, did not welcome him with open arms, and a chance to see Europe (nevermind that he was going to fight — the shooting would be over by autumn said conventional wisdom) was too much for Stanhope to resist.

All this the reader learns through Stanhope’s letters home to his younger brother, Bobby. Some letters are short, some long and rambling. Many are more revealing for what they don’t say than for what they do. Some are never even sent. Some are self-delusional. Stanhope is a soul under intense pressure, stationed on the blood- soaked killing fields of Flanders, where tens of thousands of men are sacrificed without a thought to claim a dozen yards of territory from the enemy. It is here, in the trenches scarring the French and Belgian countryside, that Stanhope lives a parody of life. Amid the bloated corpses and clouds of mustard gas, he slips from shell-crater to shell-crater amid the barbed wire of no-man’s land, a sniper picking off German soldiers careless enough to give him even half a target. When he sleeps, he dreams of an otherworldly cemetery, a beautiful garden of the dead watched over by a girl in a calico dress. A cemetery increasingly real, and increasingly filled with his comrades fallen in action.

Above all, Flanders showcases the futility and hypocrisy of war, and of World War I in particular, which was as arbitrary and unnecessary as any in history. Stanhope’s enthusiasm and earnestness turn quickly into a mindless struggle for survival, where even his deepest-held morals and values are sorely tested. Through his writings the reader is introduced to a sprawling assortment of characters: the loyal, honorable Captain Miller, who is looked down upon by superiors for his Jewish ancestry; Pierre LeBlanc, a French Canadian who delights all too much in the savagery of war; and Father O’Shaughnessy, the company priest who offers support to Stanhope, and who comes to believe in the truth of Stanhope’s graveyard dreams. All of them are swept up in the relentless killing, an orchestrated madness that scours the entire countryside and spills over into the towns and villages far beyond the front, leaving not even civilians unscathed.

Flanders is not, on any level, a happy, feel-good book. But it is powerful and edgy, a showcase of gripping, engrossing writing that poses many questions, offer few easy answers, and challenges the reader in ways few books even dream of. There are few great novels about World War I, but Flanders easily numbers among the best.

(Ace Books, 1998)