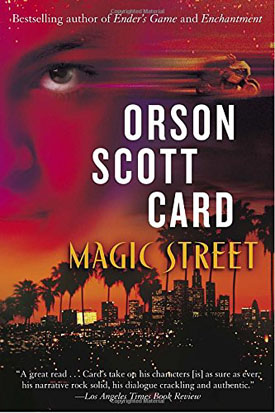

In his previous novels, Orson Scott Card seems to have dealt with either the (far) future or the (mythic) past. Magic Street is set squarely in the here-and-now — sort of.

In his previous novels, Orson Scott Card seems to have dealt with either the (far) future or the (mythic) past. Magic Street is set squarely in the here-and-now — sort of.

Baldwin Hills is a black, middle-class neighborhood in Los Angeles. The more well-to-do residents live on the hill, while the less-well-to-do live on the flats. It is a well-behaved sort of place, as such things go, at least until Dr. Byron Williams picks up a bag man on the way home. The trip is strange enough — somehow, traffic moves smoothly and swiftly, and every light is green — but when they get home, Williams discovers that his wife is pregnant and about to deliver. That certainly had not been the case that morning. The baby comes, as babies will, and the Bag Man appears with a plastic grocery bag: the baby is stillborn. The Bag Man disputes that diagnosis — “Can’t die unless you been alive, fool.” — and takes the baby. And everyone in the Williams family forgets that it ever happened (except, as it turns out, the oldest son, who does have a vague memory of the event).

Cecil Tucker, out with his friend Raymo Vine to partake of a little weed (although Cecil has his doubts about its authenticity and starts to wonder why he’s doing it anyway) discovers a baby in a plastic grocery bag, lying by the drain pipe in the little valley at the head of the neighborhood, an outpost of the Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area. Being essentially a good kid, he takes it to Ura Lee Smicher, a single lady who also happens to be a nurse. They take the baby to the hospital, where Miz Smicher is able to get him examined — and where Ceese has an encounter with a woman in black leather who almost persuades him to kill the baby, but doesn’t succeed. And so Mack Street comes to Baldwin Hills.

Mack is nobody’s and everybody’s — he wanders the neighborhood and, eventually, is welcome wherever he happens to be. And then one day, when in his early teens, he sees a house that isn’t there, and goes in.

Mack grows, and Cecil, who helps Miz Smicher take care of him, becomes his surrogate father. Throughout his childhood, Mack is a little odd — certainly no more so than anyone else in the neighborhood (although he can hear people’s dreams), but the house that isn’t there makes a difference, because it is there that Mack and Cecil, who can enter the house as long as Mack is holding his hand, meet Puck.

The story, as might be expected from Card, is a tale of growing up, of finding one’s spirit, of all those things that we do that make us, ultimately, human. That this happens to the residents of Baldwin Hills in the midst of a war between Titania — the woman in black leather, who in this story appears as Yolanda White, a motorcycle-riding “hoochie mama” who moves into the neighborhood, scandalizing the neighbors — and Oberon only adds a little bit of tension to the story. (The drain pipe is important, too.)

Card notes quite bluntly, in his Acknowledgments at the end of the book, that Magic Street was written at the instigation of Roland Bernard Brown, a friend who wondered aloud why Card had never written a black hero. Card, quite reasonably, had reservations about his ability to do that, and so Brown became his resource. As someone who has had many friends of all races and all classes in his life, all I can say is that from all I know, Card has caught it — if James Baldwin were Orson Scott Card, he might have written this book. A large part of the authenticity lies in the concrete details, and Card did actually visit the area several times. It’s also amazing to realize that Card didn’t hit on the Midsummer Night’s Dream connection until halfway through, although to call that layer of meaning an afterthought would be a terrific mistake — it really provides a sharp focus for the story. (Card’s afterword, by the way, is a wonderful read simply for the insight on how characters and novels come to be.)

This one marks a distinct departure for Card, at least as far as his novels go. It’s his entry into urban fantasy, and it’s a strong entry indeed. It’s a lean book, much leaner than the Ender Wiggin saga or the Alvin Maker series, as I remember, and funny, which is not something that one necessarily thinks of in relation to Card. It’s definitely going to become a permanent fixture in my library.

(Del Rey [Random House], 2005)