“There is, within every Italian-American family, a story about why the family left Italy… usually, at the heart of a family’s emigration story, there is a story about food….” (from the Introduction of The Milk of Almonds). This book is a collection of those stories, each with a silver hook that dragged me through my own memories as I read.

“There is, within every Italian-American family, a story about why the family left Italy… usually, at the heart of a family’s emigration story, there is a story about food….” (from the Introduction of The Milk of Almonds). This book is a collection of those stories, each with a silver hook that dragged me through my own memories as I read.

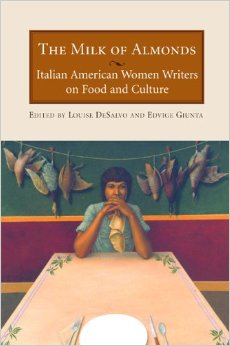

A painting by Martin Maddox (The Main Course), occupies slightly over half the cover: a table, invitingly set for one in the foreground; a shadowy Italian woman gazing at you from the other end of the table, holding a napkin as if she has just dined. The lady in the background has no plate in front of her; various ducks and wildfowl hang upside down on a string behind the woman, as if draining for tonight’s supper. It’s a powerfully mixed image that makes me think of deprivation, martyrdom, hostility, protectiveness, strength and love all at once. I was so impressed by the painting that I went looking for information on the artist: Martin Maddox, born in 1954, focused on “allegorical/psychological” realistic scenes involving women and animals. I found some other examples of his work, and he’s now on my (short) list of artists whose paintings I want hanging on my walls one day.

But this is a book review, not an art review, so I’ll move on to the rest of the cover. Above the striking picture, a creamy white background offsets a brown box with white title text in a clear and emphatic font that gives the cover a semi-formal tone. You expect, looking at this cover, to find a deeply moving and complex range of content, and that’s exactly what you find.

Just inside the inviting cover, there’s a small speed-bump: a short Editor’s Note had me worried with its warning that “we have not standardized the spelling and syntax of Italian words in this collection,” in order to keep the “integrity of the language” used by the authors of the various essays. I was concerned that I’d miss something important, since I don’t know Italian beyond a smattering of words picked up for a college trip — and perhaps I did. I have no way of knowing. Most of the Italian phrases in the book had a translation either directly with them or implied in the surrounding text, so I didn’t feel lost very often.

As I’ve said in previous reviews, I normally dislike introductions; once again I have to back away from that stance. The Introduction in Milk of Almonds is so packed with information that I could write a review just on it alone. It twines food and almonds and history and culture all together in a strong thread of friendly narrative. A stunning number of reference books are mentioned, in such a way that I’m actually eager to go find and read them. This introduction is a like a jazzy lullaby: it’s warm and comforting and exciting all at once.

The content is divided into eight parts: Beginnings, Ceremonies, Awakenings, Encounters, Transformations, Communities, Passings, and Legacies. Each section holds essays and poems that are as intense as the Introduction; although in any collection there are bound to be pieces I don’t care for or don’t understand, the balance of the work in this book is solid and beautifully written. There are far too many wonderful entries for me to comment on all of them individually; I’ll only mention one piece in each section.

Beginnings starts with “Rose and Pink and Round,” by Carole Maso, which examines breast feeding a child in a way I, childless, have never known or understood. It’s a moving essay, if somewhat puzzling at a deep level; a woman who has breast-fed would probably have gotten more out of it than I did.

The first story in Ceremonies, “Kitchen Communion” by Camilla Trinchieri, is a stunning story about family reactions to a father’s death. The adult children are anxious to get away, “each of us back to our own hideout, away from the shrinking walls of this house.” Their mother, angry at their desire to retreat, finds an unexpected way to bind them together. It’s not a comfortable story, dealing with anger and family dissension in an open, forceful way that’s common in this collection, and the ending is one to ponder for a while.

In Awakenings, the story “Big Heart” by Rita Ciresi stands out as a raw and unusual tale that winds around the physical and mental entrails of a butcher shop. “Although Mama had patronized Ribalta [the butcher] for years, she still didn’t trust him. ‘It’s not like he’s family,’ she said.” In the end, that vicious distrust guts something more precious than the money the woman haggles to save.

The starring entry, for me, in the Encounters section is “My Grandmother, a Chicken, and Death,” by Regina Barreca. Starting with a good hook — “The miracle of death I first had the privilege to witness when I was about five years old” — the book carries through a short, straightforward, potent tale about an indomitable woman and the lesson she taught a child without a word being said.

Transformations holds a gem of a poem that had me laughing in complete empathy: “lovers and other dead animals,” by Vittoria Repetto. It’s too short for an excerpt to do it justice; I’ll note that the title explains the content and leave it at that.

“Coffee an’,” in the Communities section, is another one with a terrific beginning: “Coffee and sugar were the narcotics that stimulated the days and nights where I learned about intimacy in that great and terrible school, the Italian American family.” This essay, looking at the familiar ritual of adults gossiping around the coffee table late at night, balances an honest mixture of the violence and love in a tightly knit community.

In Passings, the story “Baked Ziti,” by Kym Ragusa, is one of the most startling tales in this collection. It’s a hard look at heroin addiction, AIDS, family ties, Vietnam, and violence, all served with a heaping plate of pasta. “On a rare day alone together, Susan tells me she wants to leave my father. How he keeps doing drugs around her even though she’s trying to stay clean, fighting for her life.” It’s a narrative that pulls no punches and refuses to display easy preconceptions.

The last section, Legacies, has a fascinating tale by Maria Laurino, “Words,” which examines the immigrant battle between the culture of origin and “fitting in” to the way things are done in the new land. “I would find myself refraining from mentioning subjects as innocuous as a dinner meal. How could I tell friends that my dinner had been a dish made with kookazeel? The word sounded more like baby talk than baby zucchini….” It’s full of the meanings and inferences of dialect words, a mini-language lesson in its own right, with entertaining stories smoothing it into a great read.

The above is only a tiny sampling of the wide range of work in this book. Fennel and oregano, dandelions and rosemary, the sweet and bitter greens of life are strewn across these pages for us to inhale and experience. “You can’t eat beauty,” says a man in the Introduction, and that’s true. But curl up with this book, a cup of your favorite hot beverage, and a luxurious snack; you’ll have a treat that satisfies both body and soul.

A list of the contributors and an impressive synopsis of their publishing credits and accomplishments can be found at the back of the book.

(Feminist Press, 2002)