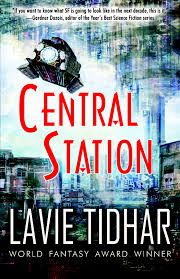

Lavie Tidhar’s Central Station is barely a novel, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Instead, it’s a loosely connected series of stories featuring a rotating cast of characters, and the gently ramshackle DIY nature of the narrative structure matches up perfectly with the DIY, maker-centric vision of the world that Central Station presents.

Lavie Tidhar’s Central Station is barely a novel, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Instead, it’s a loosely connected series of stories featuring a rotating cast of characters, and the gently ramshackle DIY nature of the narrative structure matches up perfectly with the DIY, maker-centric vision of the world that Central Station presents.

All of the plot threads circulate around the titular Central Station, a massive spaceport in more-or-less Israel that’s humanity’s gateway to the stars. But very little of the action involves the Station itself; it’s all about what the Station represents and the impact it’s had on the people living around it. Instead of brave (and hackneyed) space explorers launching themselves from this technological marvel, it’s about the lives and accomodations that people have made at its base, the way they’ve built a world around the monolith in their midst. And it’s not travelers heading to the stars who stir the pot, it’s those weary travelers returning to Earth through the station, dealing with the consequences of what they left behind.

Individuals like Boris Chang, coming home to deal with inheritances both real and imaginary, his father breaking down under the weight of implanted memories designed to remind him of his father’s deeds. Chang’s also got an old flame to deal with, the formidable Miriam Jones, and her adopted son Kranki, a product of Chang’s long-ago research on genetically engineering Messiahs. Of course, Kranki has a friend, another engineered child named Ismail, and the two exhibit certain preternatural powers, which is of concern to Ismail’s adoptive father Ibrahim the rag-and-bone man, who helps supply the “God Artist” Ezekiel with raw materials, and then there’s the robotnik priest and part-time mohel who’s advising the aged robotnik soldier who’s found love with a human woman who works captaining a VR spaceship in a massive online game, and that’s not even mentioning Miriam’s brother who falls in love with a data vampire from space named Carmel.

It is, in a word, dense, as all of these characters weave in and out of each others’ lives. Tidhar does a wonderful job of evoking the small-town sense of “everybody knows each other,” even in the shadow of the gateway to the wider physical universe the Station represents, and even in the shadow of the wider conceptual universe hinted at by the post-human AIs known as the Others and their human avatar, the Oracle. What results is a warm, generous narrative about how the simplest of human emotions – love and fear – and the most obvious of gestures – the spurned lover chasing after his beloved, even if the lover in question is a soldier from a long-forgotten war who’s long since been transmogrified into a machine, and the beloved is working through her feelings by piloting a virtual starship through a hole in virtual reality – retain their power to drive and transform us. Yes, Central Station has cyborgs and AIs and data vampires and genetically engineered magical children, but at its heart it’s a gaggle of stories about love – love across the years, love across previously unthinkable boundaries, love across generations, and love between what has come before and what is coming next.

(Tachyon, 2016)