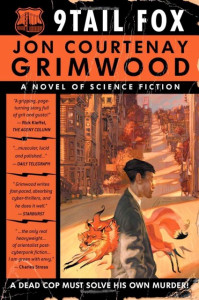

The book cover claims that Jon Courtenay Grimwood’s 9Tail Fox is “A novel of science fiction.” Considering what science fiction has become over the past generation, that could well be valid — with some qualifications. I’m going to call it “slipstream” in honor of its genre-bending tendencies and let it go at that.

The book cover claims that Jon Courtenay Grimwood’s 9Tail Fox is “A novel of science fiction.” Considering what science fiction has become over the past generation, that could well be valid — with some qualifications. I’m going to call it “slipstream” in honor of its genre-bending tendencies and let it go at that.

Bobby Zha is a San Francisco police sergeant who is murdered. He wakes up some small time later in New York in the body of a young man, Robert Vanberg, who has been in a coma since age seven. Because of the insurance settlement for the accident that caused his coma and the deaths of his parents, Vanberg is sitting on quite a bit of money. Robert/Bobby goes back to San Francisco to find out who murdered him.

Those worried about genre tropes and the bounds of genre fiction might as well leave their definitions at home on this one: there seems to be a concerted effort to plunk Grimwood’s work down in to the realm of cyber-thriller or post-cyberpunk, and maybe that holds true of some of his other books — this is the first I’ve read, and trust me, I’ll be keeping my eyes out for the others. As for 9Tail Fox itself, call it Frankenstein by way of Maltese Falcon, with some quirks of its very own. It has a small but crucial element of Chinese folklore — the nine-tailed fox of the title, a trickster and harbinger of death — and a real sense of San Francisco in its infinite variety.

The psychological realism is the most striking element. This is not an easy book and these are not easy people. Bobby Zha simply refuses to be your stock cop/hero. He’s way too human, and his fumbling efforts to reconnect with his daughter when he can’t tell her who he really is — whose soul is occupying this stranger’s body — are just a little beyond painful. You want him to be “the good guy,” and in the important formal narrative respects he is, but you start to realize that he’s also a jerk who has really screwed up his life and maybe has one chance to make something right — not everything, just one thing, maybe a couple. And bless him, he tries.

Grimwood manages to carry this realism through a cast of characters who provide what is colloquially known as “local color” — pimps, street people, the homeless, Russian émigrés, rebellious teenagers, bitter wives, rookie cops who are too innocent about the wrong things, police officers who are just trying to survive one more day. I didn’t catch a false step here.

Fair Warning: If you read the blurbs you think you’re in for a “fast-paced, absorbing” thriller, and you won’t be disappointed, although it’s not a break-neck slalom toward a neat ending. And then you find yourself thinking about it and you realize that this is a painful, beautiful story, a subtle and compassionate essay on a man who maybe didn’t always try to do his best, who got lost in life, but who finally deserves all the respect we can give him.

(Victor Gollancz, 2005)