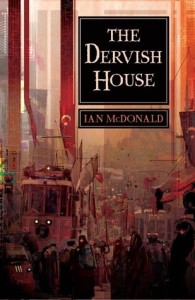

Having recently published two books set in near-future India — the novel River of Gods and the story collection Cyberabad Days — Ian McDonald turns to near-future Turkey. The Dervish House follows seven characters over seven days in 2027, as Turkey prepares to celebrate the fifth anniversary of its joining the European Union.

Having recently published two books set in near-future India — the novel River of Gods and the story collection Cyberabad Days — Ian McDonald turns to near-future Turkey. The Dervish House follows seven characters over seven days in 2027, as Turkey prepares to celebrate the fifth anniversary of its joining the European Union.

This book could be set in the same future world as the two Indian books; if it’s not the same, it’s similar. It’s very much like what our world might be in another couple of decades — hotter, more crowded, with an even starker divide between rich and poor, and teeming with technology. It’s a different world than we in the West know, though. It’s also brimming with Anatolian spirits that sometimes seem indistinguishable from the effects of nano-technology.

The cast of characters starts with Istanbul herself, the Queen of Cities, the crossroads of Asia and Europe, spraddling the Bosphorous, layer upon layer of history, conquest, triumph and tragedy, and the nexus for the flow of natural gas from Russia and the former Soviet states to the energy-hungry Eurostates. McDonald lavishes some of his best writing ever on descriptions of the city and its people.

The people we follow include Necdet (NEJ-det), a young man with a mysterious past who starts seeing djinn and other spirits after he witnesses a suicide bombing on the tram; Adnan, a 30-something high-stakes gas trader; Ayşe (I-sha), his wife, an upscale antiquities dealer; the economist Georgios, an elderly remnant of Istanbul’s once-thriving Greek population; Leyla, an ambitious country girl sent to the city to improve her family’s fortunes; and Can (jan), a 9-year-old savant with a crippling health condition that doesn’t stop him from playing Boy Detective. Their lives all intersect in the environs of the eponymous Dervish House, an ancient place of Sufi spirituality now divided into low-rent dwellings. Can and his family live on the top floor, Leyla somewhere in the middle, Georgios on the ground level and Necdet and his brother, a “street shaykh,” squat in the basement. Ayşe’s gallery is across the square, and Georgios and his aging compatriots sit in front of a tea house on the square, watching and commenting on all the residents’ comings and goings. A Greek chorus, as it were.

The book is full of clever little turns like that, and some just plain excellent writing. More on that in a minute. First, the plot threads. Adnan and three of his friends are planning to make an illegal side deal for some Iranian gas, hiding their activities among the frenetic trades on the floor of their firm, Özer Pipelines. Can, with some help from Georgios and a modified transformer-like robot toy, is attempting to unravel the mystery of why surveillance bots followed Necdet home after the tram bombing. Leyla has been hired by an upstart nano-tech firm to find a tiny ancient artifact, which we know has just been purchased by Ayşe; she, meanwhile, is on the trail of an artifact that may be more legend than reality, an ancient body mummified in honey. And Necdet’s visions are getting more and more bizarre.

With all that, The Dervish House is remarkably compact at some 350 pages. And it’s definitely a page-turner, except for some of the parts involving Adnan and his testosterone-laden friends. Maybe it’s just my perspective, but the stories of young Can and old Georgios, a retired economics expert who can still see patterns in much of the human activity that surrounds him, I found most gripping.

In the following passage, we learn about some of Georgios’s past, when he fell in with a bunch of radical students in 1980 — most of whom either were arrested or deported or fled when the Army cracked down on their activities. He had fallen in love with one of them, named Ariana, who has now been seen back in Istanbul these nearly 50 years later.

There is no more incandescent passion than love in a time of revolution. Even when the faces from the newspapers were no longer at his shoulder in the demonstrations, when more bodies without faces turned up in the prop-wash at Kadiköy and Eminönü and remote lay-bys on the Bursa Highway, nothing like that could happen to him. Love protected him like the word of God.

Themes of sound and silence, light and water, truth and subterfuge, run throughout the book. And always fire and heat. McDonald masterfully uses metaphor in a way that transcends the genre of science fiction and puts him in the realm of speculative fiction with writers like Mary Doria Russell and even, dare I say, LeGuin. One superb section, for example, begins with Georgios observing the activities of crows and ends with him publicly demolishing the authority and reputation of his old nemesis. Shortly afterward, we see Adnan at the barbershop being groomed in a highly symbolic way for his big deal day:

Hasan the barber wraps the wad of kitchen roll around the tip of the screwdriver, douses it in lighter fuel and ignites it. Quick as a knife he wafts the flame close to Adnan’s ears, left, then right, and repeats twice before he douses the brand in a flowerpot of sand on the counter. A wash of heat too quick for pain, the smell of burning hair. This is the heart of barbering, the intimate violence, the placing of yourself in the seat of a man who can bring so many blades close to your eyes, ears, nostrils, jugular.

The entire tale is a metaphor for our own times, of course, when current technology has its own light and dark essences. Although it deals in djinni and green men (!) and miraculous-seeming nano-tech, The Dervish House is more grounded in a reality Westerners will recognize than were McDonald’s two India books. One doesn’t know whether to wish for something like the future it envisions, with nano-technology bringing the third industrial revolution, or to devoutly wish that it never happens. Surely, though, one can wish for more books of this caliber from Ian McDonald.

(Pyr, 2009)