Aaron Copland is the central figure in serious American music, and Howard Pollack has produced a biography worthy of the man. His treatment of Copland in more than 500 pages is reverential but never blindly worshipful, candid without being lurid, scholarly but rarely tedious.

Aaron Copland is the central figure in serious American music, and Howard Pollack has produced a biography worthy of the man. His treatment of Copland in more than 500 pages is reverential but never blindly worshipful, candid without being lurid, scholarly but rarely tedious.

Copland dedicated his professional life to creating a recognizable American style of orchestral music. His music was often misunderstood by his peers and ignored by the public, but toward the end of his creative career he was recognized by musicians and audiences around the world as the voice of American music.

Pollack claims, toward the end of his work, that “…from the start of his career, Copland set out to compose music that was ‘recognizably American’ and that reflected ‘the American scene…in musical terms.'” Pollack demonstrates his thesis amply in this thorough biography.

A music historian and professor, Pollack has written not a popular biography, but an in-depth exploration of Copland’s music primarily, and his life secondarily. Much of the book consists of detailed analyses of the composer’s key works, from his early student piano pieces, to the beloved ballets, to the less accessible works done in the twelve-tone style. The author digs into Copland’s work in the spirit of divining and divulging the composer’s ideas, and succeeds admirably. But be warned, there is a lot here that only those with some musical training will understand.

The story is fascinating, for all that. Pollack takes us, more or less chronologically, through all the major periods of the composer’s life. Many of the chapters, however, also look at major themes running through Copland’s life and works, necessarily breaking the strict flow of time.

Copland was born with the century, to Jewish immigrant parents in Brooklyn in 1900. In many ways, his life’s story parallels that of the century. He was part of the American expatriate arts scene in Paris in the 1920s, returned home to labor in obscurity in the ’30s as he began to give birth to his vision, came to public notice in the ’40s through his work on film scores and ballets, survived with grace the Red Scare of the ’50s, and created a number of modernist works in the ’60s. His one regret, expressed near the end of his life, was that he never wrote a “grand” opera.

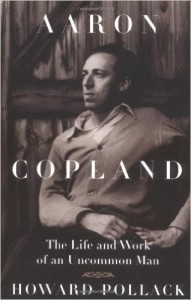

Pollack candidly but tastefully discusses Copland’s homosexuality as part of his investigation into the artist’s life. Although he concentrates more on the music than the man, we get a good picture of Copland’s personality. He emerges as a man of deep humility, but at the same time one who never wavered in his belief in his own art. He was subjected to intense criticism in all the phases of his career, and he gracefully accepted it, but never let it sway him from his course. This calm but intense self-confidence is evident in the excellent portrait that graces the book’s cover.

Aaron Copland was much more than the creator of Rodeo, Fanfare for the Common Man and Appalachian Spring, although those are his best-known works today, just a decade after his death. Pollack covers all the bases and points the interested listener toward the 100 or so other works Copland composed. The book features a discography and, at least as valuable, suggested readings on the vast topic of American music.

If you’ve ever considered delving further into Copland’s ouevre, this book is an excellent place to start, and a good companion for your journey.

(University of Illinois Press, 2000)