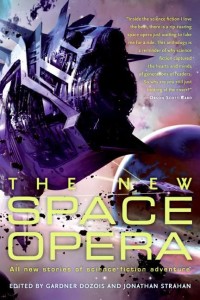

It’s been a long time since I read a science fiction anthology. Which is weird, because I’ve always liked reading them. In fact, I discovered sci-fi with a little paperback anthology, The Ninth Galaxy Reader, edited by Frederik Pohl, in 1967. I still have it, and several similar volumes. But lately, when I read science fiction, I’ve been going for massive tomes and big series of novels. Plowing through the back catalog of Iain M. Banks, for instance, or waiting for another release from Dan Simmons. So this hefty anthology, The New Space Opera was a welcome change of pace, or return to form, or something like that.

It’s been a long time since I read a science fiction anthology. Which is weird, because I’ve always liked reading them. In fact, I discovered sci-fi with a little paperback anthology, The Ninth Galaxy Reader, edited by Frederik Pohl, in 1967. I still have it, and several similar volumes. But lately, when I read science fiction, I’ve been going for massive tomes and big series of novels. Plowing through the back catalog of Iain M. Banks, for instance, or waiting for another release from Dan Simmons. So this hefty anthology, The New Space Opera was a welcome change of pace, or return to form, or something like that.

Of course, “space opera” is what all science fiction used to be, up until about the 1970s or so. Thrilling tales of adventure in outer space, usually featuring huge starships, weird aliens, strange planets and battles, either physical or of wits. “Romantic adventure set in space and told on a grand scale,” the editors offer as a brief definition in the book’s Introduction. This well-informed piece goes on to give a short history of the genre, including how it fell from favor in the late 1960s or early ’70s, due to a convergence of factors: a “New Wave” in SF, which focused on more introspective and sociological themes, the discovery that there probably wasn’t life on other planets in our solar system, and the feeling that Einsteinian relativity nixed the idea of warfare and communication on a galactic scale. And then, of course, how it was revived in the ’80s and ’90s. The editors conclude by saying that, “we weren’t especially concerned about getting stories that met this definition or that … Instead we were looking for great new stories by some of the best writers working in the field.”

By that definition, they’ve succeeded smartly. At just over 500 pages, the book contains stories from 18 different authors. You can get more details at the HarperCollins website.

Some hew more closely to what I think of as space opera than others. Ken MacLeod’s “Who’s Afraid of Wolf 359?” follows a Sol system agent to another system, where he’s sent to help quell a rebellion — but it doesn’t quite work out that way. It includes some splendidly droll dialog between the protagonist and the ship that takes him on his mission:

“That was a landing,” said the box. “Yes,” I said. “You might have tried to avoid the trees.” “I could not,” said the box. “Phytobraking was integral to my projected landing schedule.” “Phytobraking,” I said. “Yes. Also, the impacted cellulose can be used to spin you a garment.”

“Valley of the Gardens” by Tony Daniel is told in alternating sections that take place in different time frames: one involving a battle with “beings” from another dimension for possession of a special planet; and the other taking place on that planet either long before or long after that battle, we don’t find out until near the end of the story. The non-battle part concerns a farmer tending crops in a lush valley who falls in love with a girl who lives in the desert across the stone wall from his farm. She goes away to another part of the continent for part of each year — but not before she gives him a special telescope that lets him see and even hear and feel her, no matter how far away she is.

In “Dividing the Sustain,” James Patrick Kelly writes a tale of interstellar intrigue, with not a little humor thrown in. Starting with the opening sentences: “Been Watanabe decided to become gay two days before his one hundred and thirty-second birthday. The colony ship had been outbound for almost a year of subjective time and the captain still could not say when they might make planetfall.” There’s plenty more of that blend of space travel and social satire in this delightful tale that keeps you guessing right up to the last page.

There’s social commentary of another sort that is pertinent to our current world situation of pre-emptive war, in Alastair Reynolds’ “Minla’s Flowers.” A space traveler happens upon a world torn by constant but old-fashioned war between two main factions. The world is also doomed to be destroyed by a cosmic accident in 70 years. So the pilot, Merlin, makes the fateful decision to share some of his futuristic technology with one of the factions in hopes that they’ll unite with their rival brethren in time to flee their planet before it dies. As Merlin emerges from cold-sleep every 20 years or so to check on their progress, he follows with chagrin their progress through conflicts that more or less mirror Earth’s 20th century wars, and then into more horrific territory.

Humans’ tendency to misunderstand their enemies has long been a staple theme of space opera. Nancy Kress takes another look at it in “Art of War,” with a protagonist who is an art historian in the employ of the military. The twist is, his mother is the human fleet’s commanding officer and she views him as a coward. He’s sent to the recently conquered enemy planet to try to make sense of the huge storehouses they’ve found of looted human art and artifacts. But will the military listen to his frightening conclusion? Hmm, ignoring intelligence we don’t want to hear … sounds familiar.

Stephen Baxter’s “Remembrance” is an even more chilling tale that looks at humanity’s capacity for war and predilection for revenge. Humans have recovered from and conquered the alien invaders who destroyed Earth centuries before, when they make parallel discoveries. Some of the invaders have survived in cold storage on one of Earth’s moons; and there’s an old man who is the last in a long line of individuals who were entrusted with the real story of what happened to Earth, an oral history told to only one boy in each generation. The military leaders have to decide what to do with this information.

There are a few stories that don’t really fit my definition of space opera, but they’re excellent anyway. I’m thinking mainly of Mary Rosenblum’s “Splinters of Glass” and Robert Silverberg’s “The Emperor and the Maula.” The former takes place in the ice canyons of Jupiter’s moon Europa, where an “ice moss” miner’s former girlfriend has tracked him down, unwittingly leading to him sinister agents from his past on Earth. The latter is a splendid retelling of “The Thousand and One Nights,” with a human woman playing the role of Scheherezade, catching the attention of the Emperor of All Space and Time with her heart-rending tale of the loss of her home planet (Earth) and exile in the cold, cruel galaxy.

I was unprepared for as much humorous writing as I found. Walter Jon Williams, in “Send Them Flowers,” gives us the tale of a couple of ne’er-do-wells on the run from … well, somebody, it’s not quite clear who. They put down in a bizarre “probability” space in their yacht Olympe, and the first mate Tonio proceeds to wreak havoc among the port’s womenfolk. There is, of course, the obligatory scene in the space bar: “By morning the bar was closed and locked, the dance floor was empty, I was hungry and broke and melancholy, and Tonio’s girl had gone insane. She was crying and clutching Tonio’s leg and begging him to stay.” Needless to say, they get into lots of trouble, on a galactic scale, and manage to get out of it by their wits.

Many writers must either be actors themselves or wish they could be, because tales of itinerant acting companies are a staple of both literary and genre fiction. That’s why it’s no surprise to find two of them here. The first is the satiric Kage Baker story, “Maelstrom,” in which an impresario on a partially terraformed Mars builds a cathedral-like theater space to entertain the miners. I couldn’t help thinking of Robertson Davies’ *Lyre of Orpheus* as I read the story of the rough but wealthy businesswoman Mother Griffith, the impressario Mr. Morton and their travails as they hire two washed-up Earth stars to assist in their production of Morton’s new adaptation of Poe’s “Descent into the Maelstrom.” Needless to say, nothing goes quite as planned, with the leading lady’s unexpected pregnancy and the effect of lower gravity on the leading man taking their toll.

Dan Simmons’ novella of another interstellar acting troupe finishes the book on a strong note. “Muse of Fire” takes a futuristic Shakespearean company, The Earth’s Men, on a journey through various parts of the space-time continuum, where they are serially dragooned and forced to perform ever-more-difficult plays from The Bard’s repertoire, for ever-higher stakes. Once again, the setup includes a long-ago conquering of Earth by a much higher civilization, which has ruined the planet’s environment and scattered the survivors around the galaxy, most as blue-collar laborers (“arbeiters”), a few white-collar bean-counters (“doles”), and the occasional traveling actors. Simmons uses plenty of mumbo-jumbo relativistic science and his trademark earthy humor that somehow sustains his hapless characters in the face of a universe that vacillates between cruelty and indifference. Even in the face of the annihilation of their species, the egotistic actors bicker over what play to perform and who gets what role. This one’s told from the point of view of a youngish fellow who usually gets stuck playing a spear-carrier, who leaps at the opportunity to play Romeo opposite the girl of his dreams as Juliet, in conditions that are short of ideal, to say the least.

Only a couple of the stories just didn’t work for me, both of them more outlandish works of imagination than pure space opera. Both Robert Reed’s “Hatch” and Ian McDonald’s “Verthandi’s Ring” have baroque plots involving post-humans who don’t give the reader much to identify with. But two out of such a hefty book is quite a good percentage.

If you like SF at all, The New Space Opera should be on your summer reading list.

(EOS, 2007)