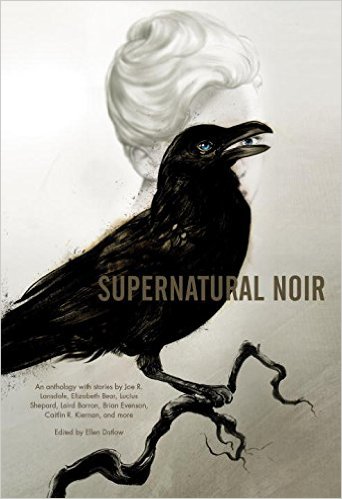

Datlow In Ellen Datlow’s Supernatural Noir, the gritty realism of noir embraces the nightmare imaginings of supernatural horror in order to offer up sixteen stories rich in style, shadows, and psychological complexity.

Datlow In Ellen Datlow’s Supernatural Noir, the gritty realism of noir embraces the nightmare imaginings of supernatural horror in order to offer up sixteen stories rich in style, shadows, and psychological complexity.

Defining the genre of noir remains a tricky business–ask half a dozen noir fans what noir is, and you’ll probably get half a dozen answers. In her introduction to this anthology, Ellen Datlow provides us with two. The first is her own very general “Noir is an attitude, a stance, a way of looking at the world,” while the second is a more specific quote from critic Paul Duncan, who focuses more on the preoccupying action and tone of noir, which is “used to describe any work, usually involving crime–that is notably dark, brooding, cynical, complex, and pessimistic.”

For myself, I find the definitions of noir as a whole less interesting than the elements of which it is made: the loser-protagonist, the femme-fatale who is often both love interest and nemesis, the labyrinthine cityscape or landscape through which the protagonist wanders in his or her increasingly desperate determination to solve the crime or unearth the secret (what Raymond Chandler described as “the hidden truth”), and the ultimate realization on the part of the protagonist that such resolutions and revelations will bring neither a sense of justice nor a sense of peace in a world so riven by moral ambiguities. Noir shares many of these elements with horror, as both genres can trace their literary roots back to the gothic novel, while the film genres of noir and horror were both indelibly shaped by many of the German expressionist directors of the 1920s and 1930s, directors such as Fritz Lang, who directed both “Metropolis” (1927) and “m” (1931).

With their shared themes and influences, noir and supernatural horror have been blended together in such notable novels as William Hjortsberg’s 1978 novel Falling Angel (which became the basis of the 1987 film “Angel Heart”), Clive Barker’s Harry D’Amour stories and, more recently, a number of novels by Tom Piccirilli, whose story, “But For Scars,” is one of the most stunning contributions in Supernatural Noir. The anthology as a whole, however, is unusually strong in the number of superb stories contained within.

The collection is off to a strong start with Gregory Frost’s atmospheric story, “The Dingus,” which follows a former boxing manager as he attempts to discover who killed a former protegé. Frost does an outstanding job at evoking the tone of a classic noir story, as does Paul G. Tremblay in the next story, “The Getaway,” which is a Twilight Zone-style tale about a bank holdup gone very wrong.

“Mortal Bait” by Richard Bowes is another of the stunners in this collection. It follows a human private eye as he attempts to solve a case set in a post-World War II New York City which includes fey who have been fighting a parallel war in their own realms.

Two stories which I did not find particularly noirish were “Little Shit” by Melanie Tem, in which a young woman with various physical mutations which allow her to change her physical appearance uses herself as bait as part of a sting operation to catch pedophiles, and “The Romance” by Elizabeth Bear, in which a middle-aged Baby Boomer finds herself haunted by an unnerving carousel. Both of these are solidly-written stories, despite the fact that they didn’t strike me as particularly noirish.

In “Ditch Witch” by Lucius Shepard, a young drifter and con artist picks up the wrong runaway, while in Jeffrey Ford’s “The Last Triangle,” a homeless addict is drawn into attempting to prevent a murder.

Laird Barron’s “The Carrion Gods in Their Heaven” is another one of the drop-dead perfect stories in this collection. It is set in an isolated cabin in the woods where a woman is hiding out from an abusive husband, but soon discovers that there are much more terrifying things in the woods, and maybe within her own self. As always, Barron creates a story rich with detail and psychological complexity, and he makes brilliant use of one of noir’s hallmark ingredients, the portrayal of landscape to intensify a sense of physical and mental isolation.

“Dead Sister” by Joe R. Lansdale provides a relatively lighter note in which a PI finds himself staking out a graveyard as he attempts to find out why one of the graves looks like something is trying to get out–or to get in. The humor in this story offers something of a respite before it’s off to the pulse-pounding horror again with “Comfortable in Her Skin” by Lee Thomas, in which a deceased mobster’s girlfriend plans the perfect crime.

Tom Piccirilli’s “But For Scars” is, in my opinion, the best story in a collection which seems to offer up winner after winner. In “But For Scars,” a former gang member becomes involved in uncovering the tragic past of a young girl. The protagonist is a hard case who, to his own surprise, still has a soft spot in his heart, and it is Piccirilli’s ability to create characters who are incredibly flawed and yet still capable of being emotionally tender which makes his stories so satisfyingly complex.

“The Blisters on My Heart” by Nate Southard features another hard case with a heart of gold, while “The Absent Eye” by Brian Evenson is about a man who can perceive a reality to which most humans are happily oblivious.

Caitlín R. Kiernan’s “The Maltese Unicorn” is an atmospheric period piece about a bookseller with some shady connections to the world of the supernatural who reluctantly gets dragged into a search for a stolen magical artifact. Kiernan’s literary references are always sharp and clever, and it’s worth pointing out that Sam Spade, as originally written by Dashiell Hammett in The Maltese Falcon was more amoral than the charming character he was portrayed as by Humphrey Bogart in the film.

Moral ambiguity and double crosses are key ingredients in the final two stories. “Dreamer of the Day” by Nick Mamatas is a twisty little tale in which a woman discovers that getting what you want is sometimes just the beginning of the nightmare, and John Langan’s “In Paris, In the Mouth of Kronos” adds a military spin to a story in which the cruelties of war and revenge unearth something even more terrifying.

Supernatural Noir is recommended for fans of horror and noir. It also provides a great introduction to noir for horror fans who are unfamiliar with the genre.

There’s an interview with Ellen Datlow on editing this anthology.

(Dark Horse, 2011)